Last updated: January 7, 2023

Article

"A Desperate Leap for Liberty": The Escape of William and Ellen Craft

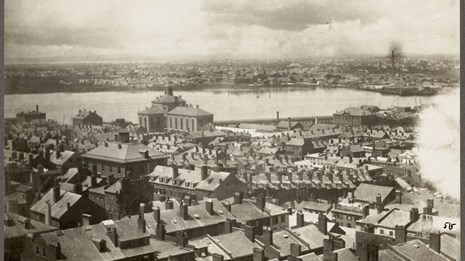

Boston served as a destination for many people escaping slavery on the Underground Railroad. Freedom seekers arriving in the city found that Boston's tightly knit free Black community provided support and a welcome sanctuary as they began their new lives. This article highlights the journey of two freedom seekers, William and Ellen Craft, who escaped to Boston. To explore additional stories, visit Boston: An Underground Railroad Hub.

Growing up enslaved in Macon, Georgia, William and Ellen Craft hoped to one day escape. In December 1848, they devised a plan to disguise Ellen, who had lighter skin, as a sickly white male slaveholder, with William as "his" faithful enslaved man. After four days of traveling, they succeeded in their quest for freedom by first arriving in Philadelphia and then later settling in Boston. However, the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law brought the threat of slave catchers, forcing William and Ellen Craft to flee to England to ensure their safety. The Crafts' story exemplifies the bravery, ingenuity, and perseverance of many on the Underground Railroad willing to risk everything for freedom.

Explore the story map below to learn about William and Ellen Craft's journey to freedom. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Footnotes

[1] William Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or, The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery (337 Strand, London: William Tweedie, 1860), https://archive.org/details/runningthousandm00craf/page/88/mode/2up?q=may, 13, 2, 16, 27, 29.

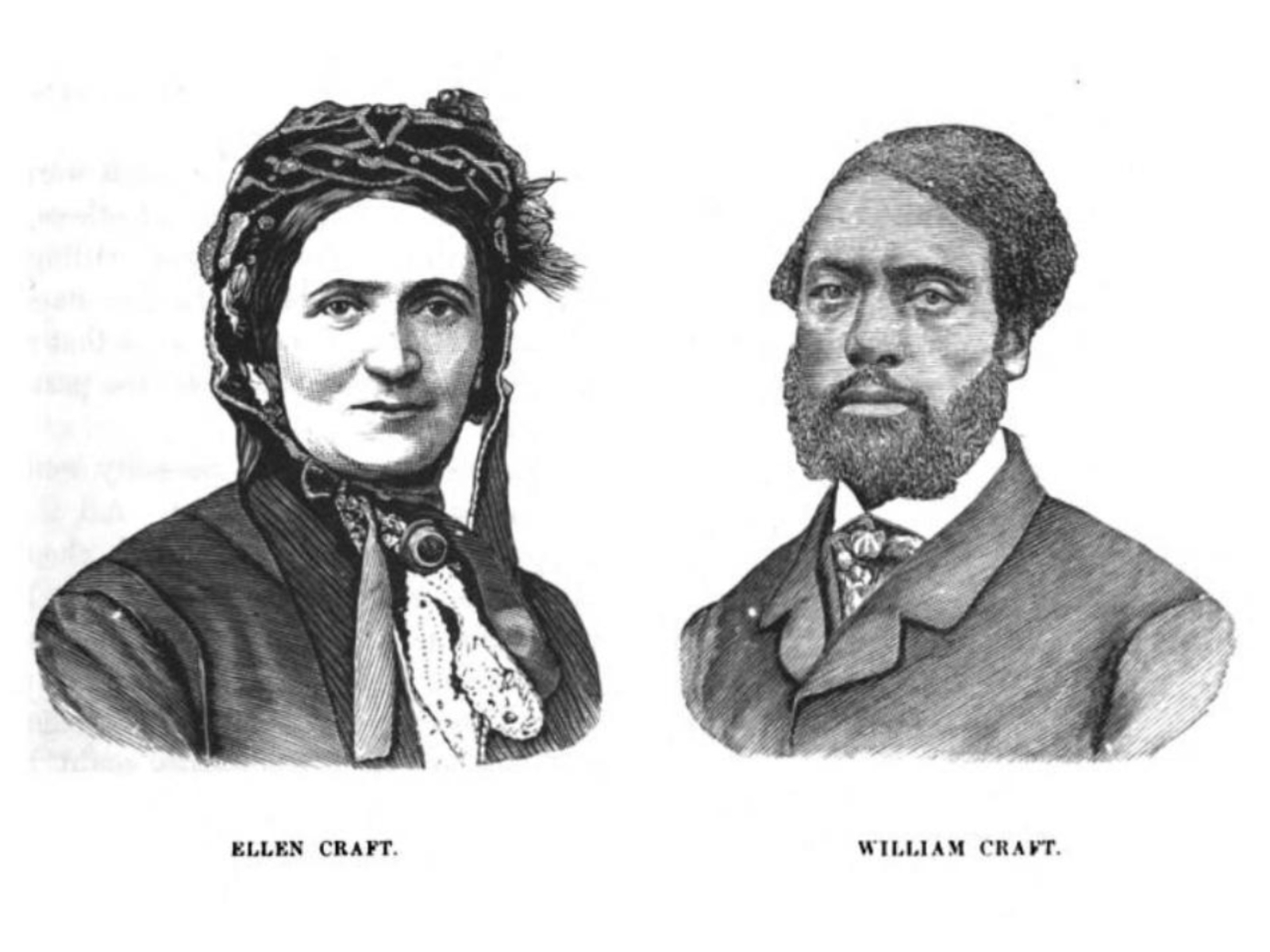

Image: William Still, Still's Underground Rail Road Records: With a Life of the Author. Narrating the Hardships, Hairbreadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom (United States: William Still, 1886), https://www.google.com/books/edition/Still_s_Underground_Rail_Road_Records/KD9LAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover, 368.

[2] Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 29, 30, 31.

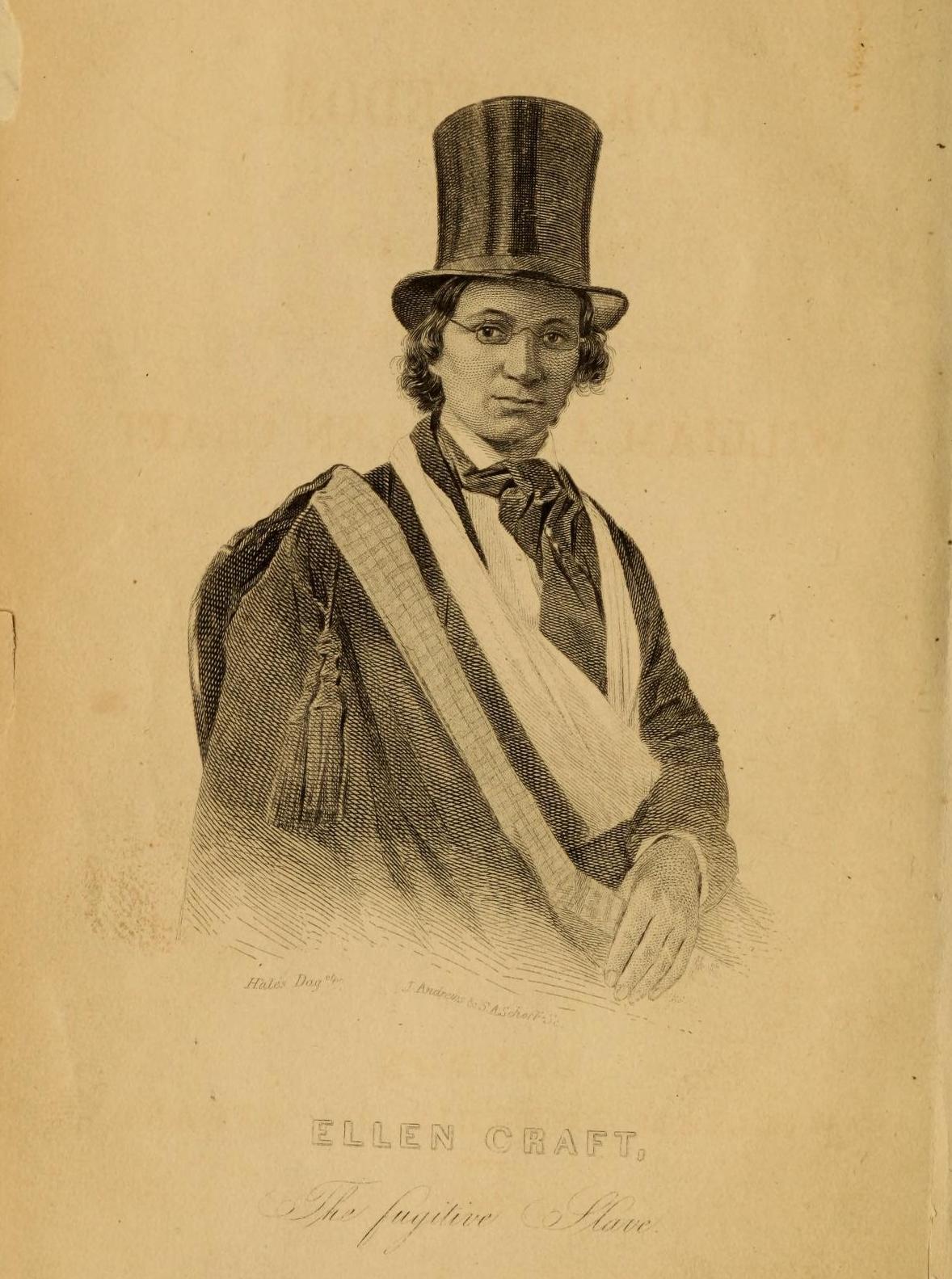

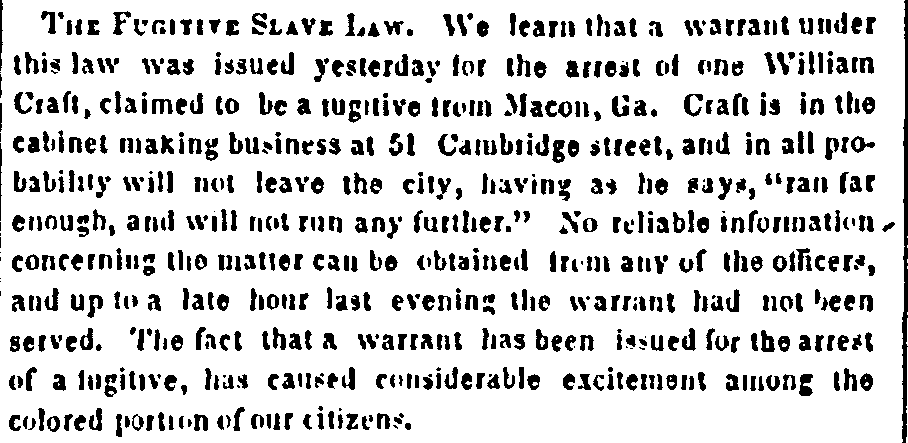

Image: Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom.

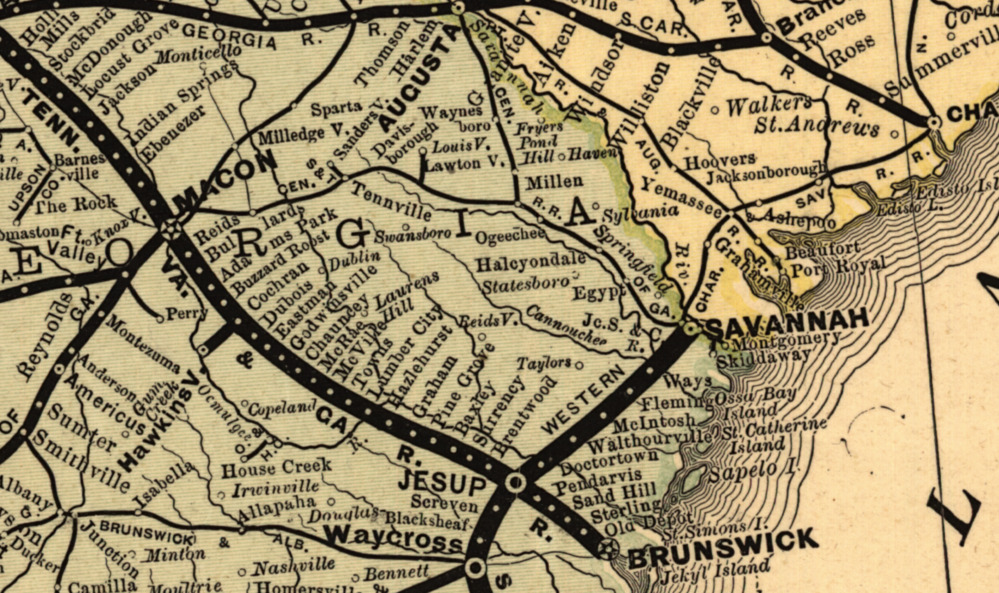

[3] Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 41, 42, 43-45; “The Crafts: An Extraordinary Path to Freedom,” The Savannah College for Arts and Design, https://www.scadmoa.org/sites/moa/files/2019-07/The-Crafts-lesson-plan.pdf; Marion Smith Holmes, “The Great Escape from Slavery of Ellen and William Craft,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 16, 2010, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-great-escape-from-slavery-of-ellen-and-william-craft-497960/.

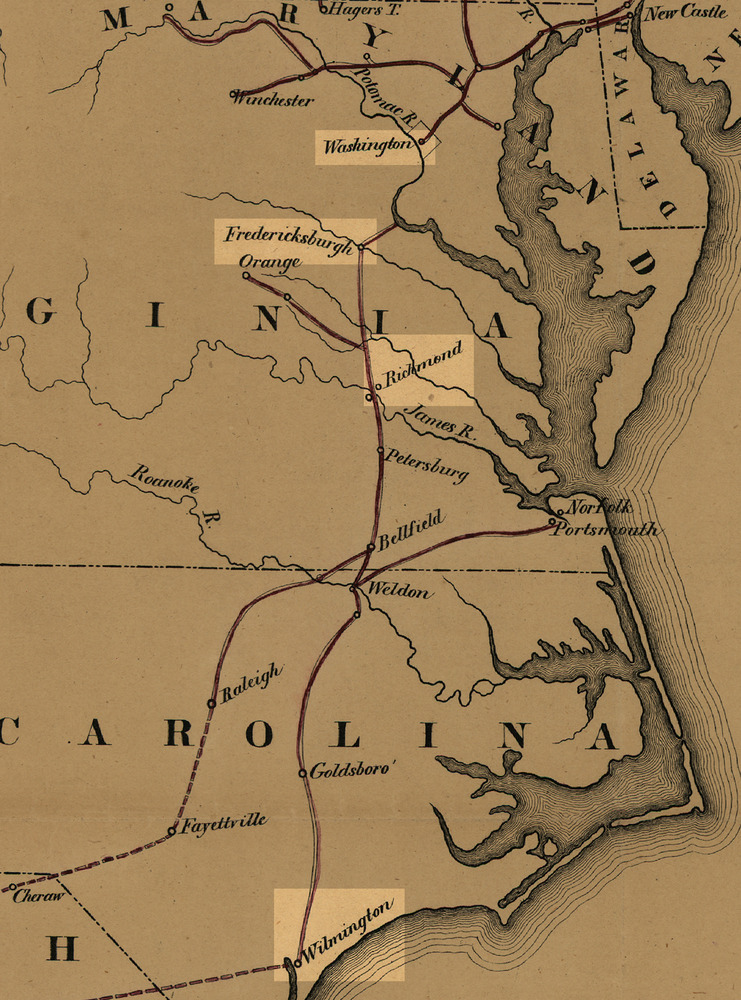

Image: Rand Mcnally And Company, and Tennessee Virginia, “The Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia Air Line; the Shenandoah Valley R.R.; Norfolk & Western R.R.; East Tennessee, Virginia, & Georgia R.R. its leased lines, and their connections” (Chicago, 1882), Map, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688846/.

[4] Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 45-46, 48-50.

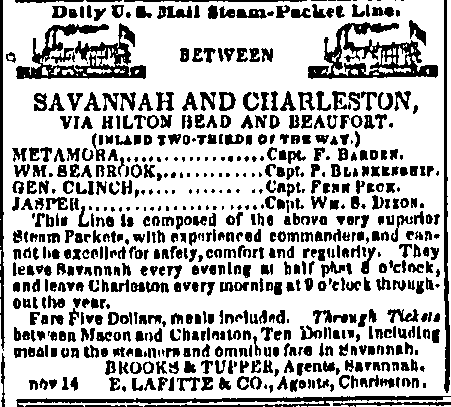

Image: “Daily U.S. Mail Steam-Packet Line,” Savannah Republic (Savannah, Georgia), January 12, 1850, Genealogy Bank.

[5] Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 54-56; Holmes, “The Great Escape from Slavery of Ellen and William Craft,” Smithsonian Magazine.

Image: George N. Barnard, “Charleston, S.C. The Post Office (old Exchange and Custom House, 122 East Bay),” 1865 [April], Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018666912/.

[6] Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 58, 61, 68.

Image: United States Congress, House of Representatives, “Skeleton map showing the rail roads completed and in progress in the United States and their connection as proposed with the harbor of Pensacola, and its relative position to the various important ports on the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic coast and in the West Indies” (Washington?, 1848), Map, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/gm70005376/.

[7] Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 70, 71, 73; William Still, Still's Underground Rail Road Records: With a Life of the Author. Narrating the Hardships, Hairbreadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom (United States: William Still, 1886), https://www.google.com/books/edition/Still_s_Underground_Rail_Road_Records/KD9LAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover, 369.

Image: Edward King and James Wells Champney, “The Great South: a Record of Journeys In Louisiana, Texas, the Indian Territory, Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, And Maryland” (Hartford, Conn.: American Pub. Co., 1875), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nc01.ark:/13960/t6c26483h&view=1up&seq=747, 733.

[8] Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 79, 82, 83, 85-86; “The Crafts: An Extraordinary Path to Freedom,” The Savannah College for Arts and Design.

Image: William E. Morris, and Robert Pearsall Smith, “Map of Bucks County, Pennsylvania: from surveys” (Philadelphia: R.P. Smith, 1850), Map, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2012590185/.

[9] Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 (New York: Penguin, 2012), 185; Still, Still's Underground Rail Road Records, 370; Kathryn Grover and Janine V. Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," Boston African American National Historic Site, (2002) 132; “The Crafts: An Extraordinary Path to Freedom,” The Savannah College for Arts and Design; Barbara McCaskill, "William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891)," New Georgia Encyclopedia, July 16, 2020, accessed 19 August 2020, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/william-and-ellen-craft-1824-1900-1826-1891; “The Fugitives in Kingston,” The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts), February 9, 1849, Genealogy Bank; “William and Ellen Craft,” The Liberator, March 2, 1849, Genealogy Bank; “Welcome to the Fugitives,” The Liberator, April 6, 1849, Genealogy Bank.

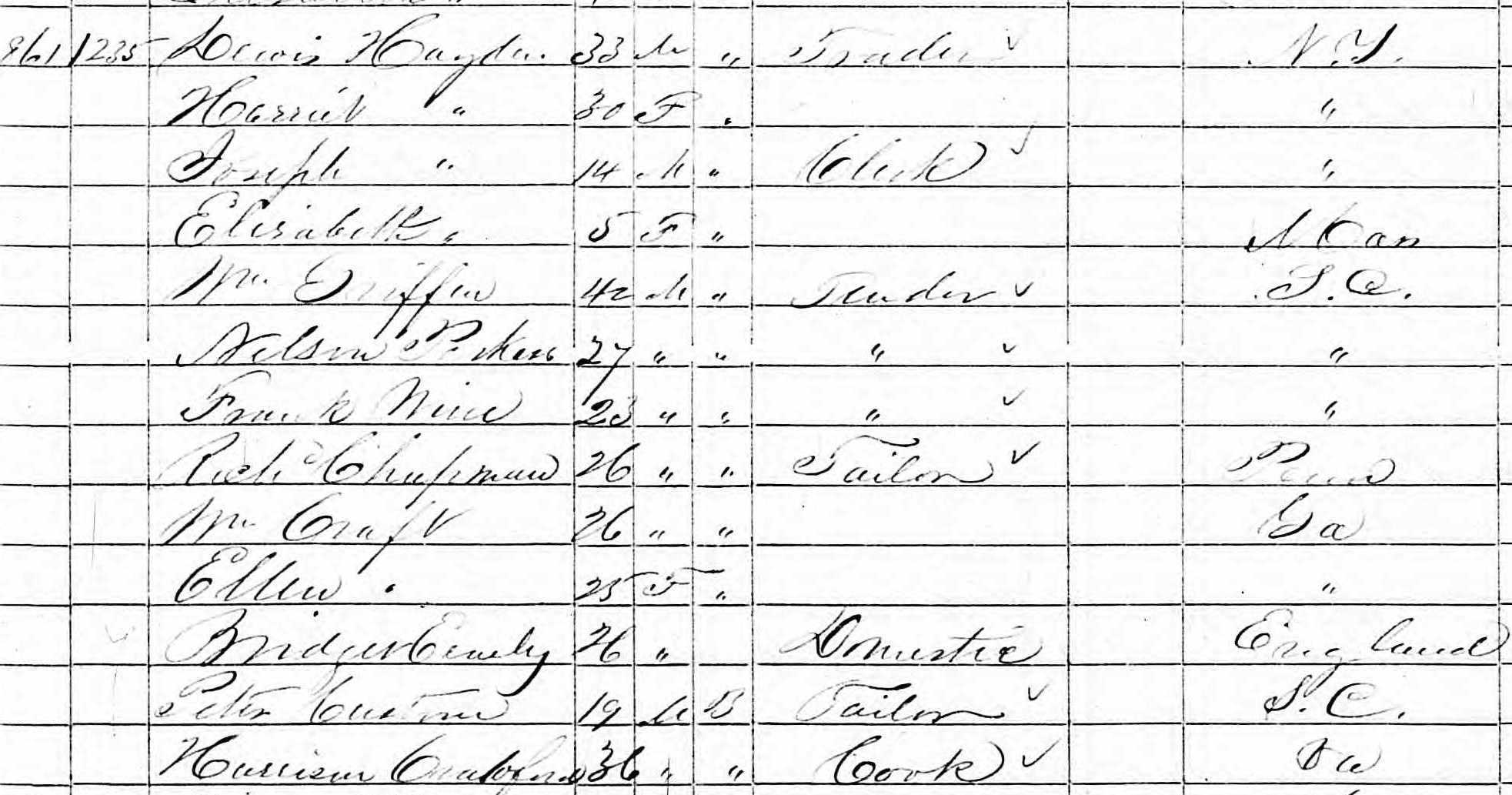

Image: United States Census Bureau, "United States Census, 1850," database with images, Genealogy Bank, Boston, ward 6, Suffolk, Massachusetts, United States.

[10] “The Fugitive Slave Law,” Boston Courier, October 26, 1850, Genealogy Bank; “John Knight’s Account of the Attempt to Recover Craft,” Daily Atlas (Boston, MA), November 22, 1850, 2, Genealogy Bank; Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 89-90; Still, Still's Underground Rail Road Records, 371; McCaskill, "William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891);" “A Story of the Fugitive Slaves the Escape of William and Ellen Craft” Worcester Daily Spy (Worcester, Massachusetts), January 26, 1890, 6, Genealogy Bank; "Local Affairs," Boston Daily Times, October 29, 1850. 2, Genealogy Bank.

Image: “The Fugitive Slave Law,” Boston Courier, October 26, 1850.

[11] Still, Still's Underground Rail Road Records, 373; "A Story of the Fugitive Slaves the Escape of William and Ellen Craft" Worcester Daily Spy (Worcester, Massachusetts), January 26, 1890, 6, Genealogy Bank; Grover and Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," 133-134; Harold Parker Williams, "Brookline in the Anti-Slavery Movement," Brookline Historical Publication Society no.18 (1899), http://www.brooklinehistoricalsociety.org/history/publications/seriesTwo/18.html.

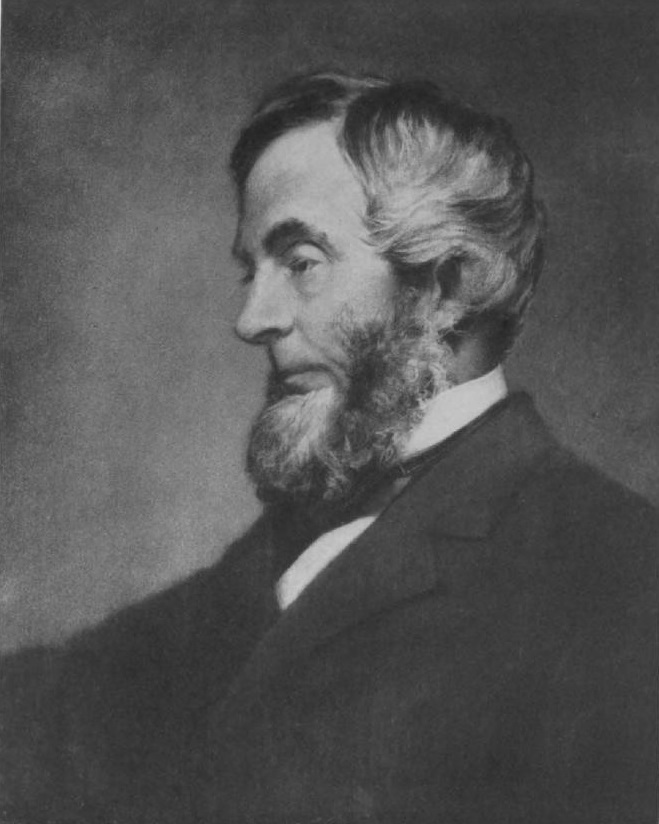

Image: Massachusetts Historical Society, "Illustration: George S. Hillard,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 19, January 1, 1881, https://archive.org/stream/jstor-25079578/25079578#page/n1/mode/2up.

[12] Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 89, 90; Grover and Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," 133-135; “Fugitive Slave Excitement,” Massachusetts Spy (Worcester, Massachusetts), October 30, 1850, 2, Genealogy Bank; "News Article," Boston Herald, November 1, 1850, 4, Genealogy Bank; “A Story of the Fugitive Slaves the Escape of William and Ellen Craft” Worcester Daily Spy (Worcester, Massachusetts), January 26, 1890, 6, Genealogy Bank; Vincent Yardley Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1902), https://archive.org/details/lifecorresponden02bowd/page/n399/mode/2up?q=craft, 373; Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom, 186; “Proposal to Buy William and Ellen Craft,” Pennsylvania Freeman (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), November 28, 1850, Genealogy Bank; “John Knight’s Account of the Attempt to Recover Craft,” Daily Atlas (Boston, Massachusetts), November 22, 1850, 2, Genealogy Bank; “Fugitive Slave Matters,” Worcester Palladium (Worcester, Massachusetts), November 6, 1850, Genealogy Bank.

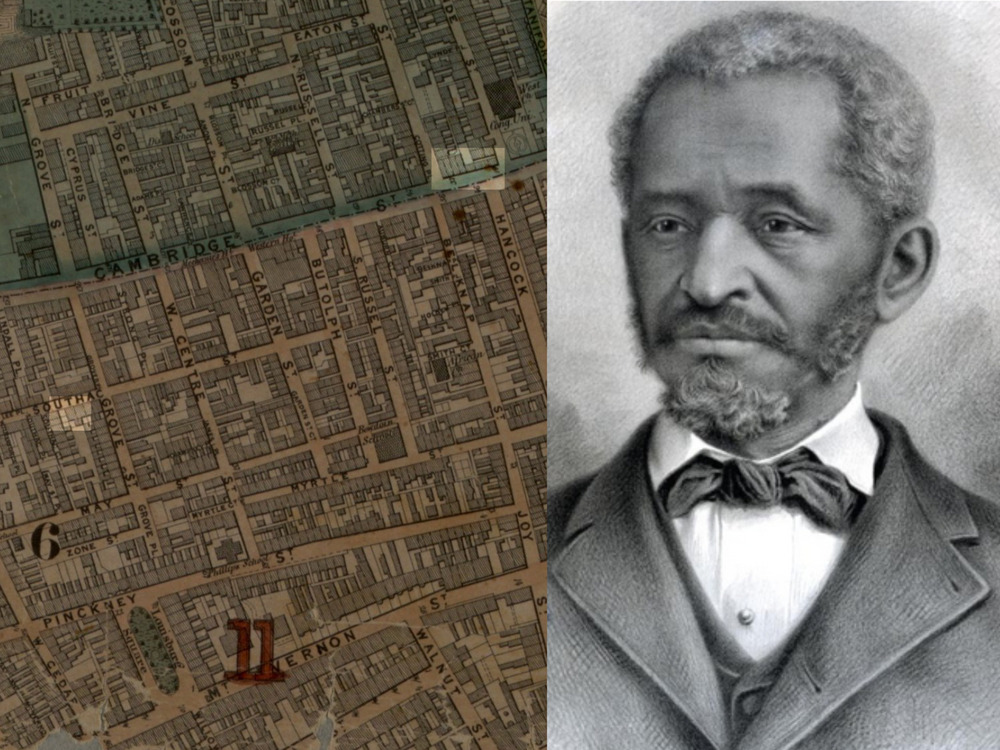

Image: J. Slatter, B. Callan, Matthew Dripps, Lemuel Nichols Ide, and Ferd, Mayer & Co., "Map of the city of Boston, Massts., 1852." (New York/Boston, M. Dripps/L.N. Ide 1852), Map. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/x059c9526.

[13] Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 93; Still, Still's Underground Rail Road Records, 371; “Marriage of the Two Fugitive Slaves,” Spirit of Jefferson (Charles Town, West Virginia), November 12, 1850, 3, Genealogy Bank; Grover and Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," 135.

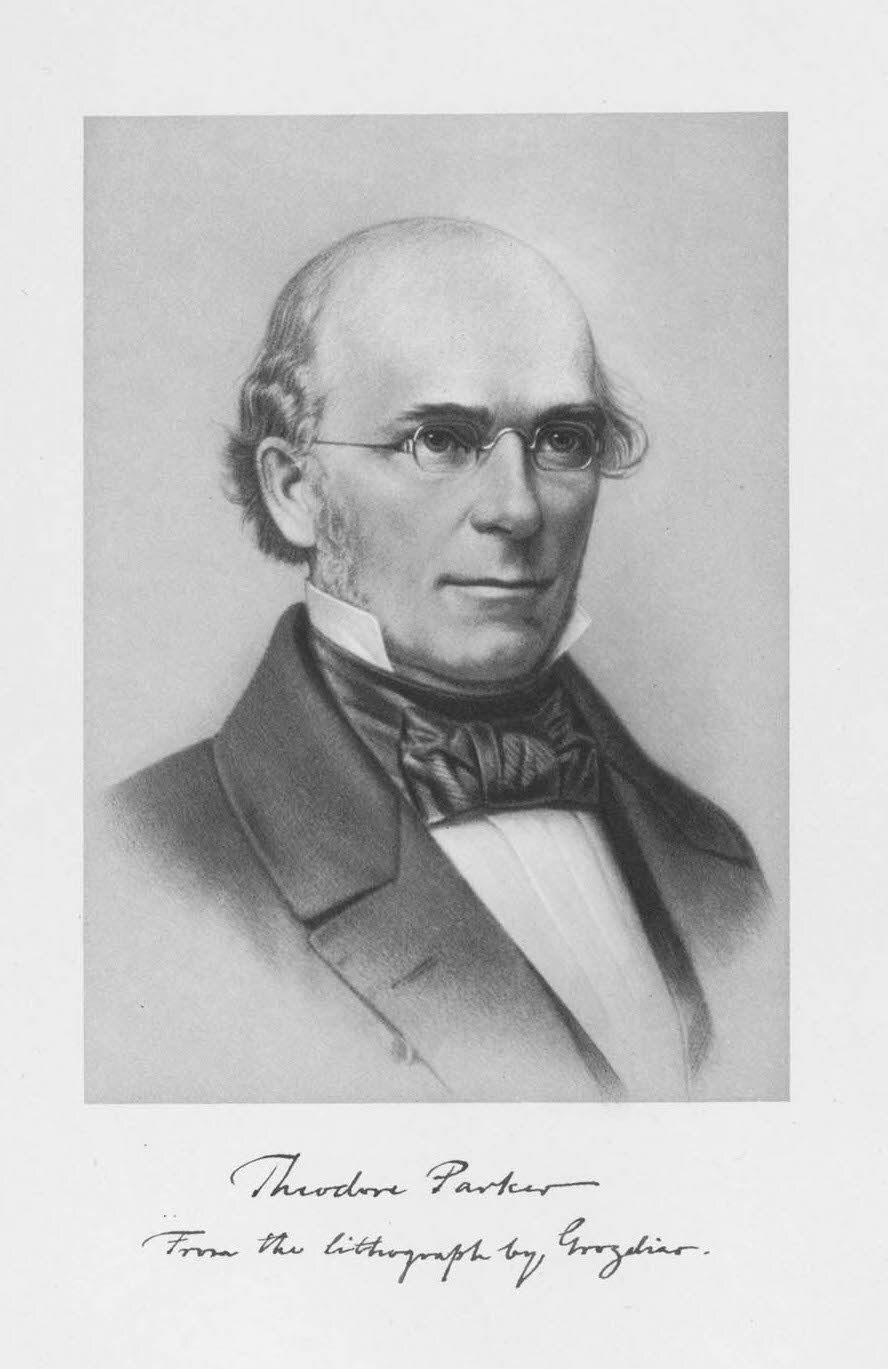

Image: Massachusetts Historical Society, “Theodore Parker,” http://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=1352&mode=large&img_step=1&.

[14] Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 101-102, 104-106, 106-107.

Image: A. Ruger, “Panoramic view of the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia” (N.P, 1879), Map, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/73693337/.

[15] Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 108-109; “From the London Morning Advertiser. William and Ellen Craft,” The Liberator, September 26, 1851, 4, Genealogy Bank; Still, Still's Underground Rail Road Records, 375; McCaskill, "William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891);" Holmes, “The Great Escape from Slavery of Ellen and William Craft,” Smithsonian Magazine; “Arrival of William and Ellen Craft in England,” The Liberator, January 24, 1851, Genealogy Bank.

Image: Louis Haghe, Joseph Nash, and David Roberts, “Dickinson's Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, from the originals painted for ... Prince Albert, by Messrs. Nash, Haghe and Roberts,” (London: 1854), British Library, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/dickinsons-comprehensive-pictures-of-the-great-exhibition-of-1851.

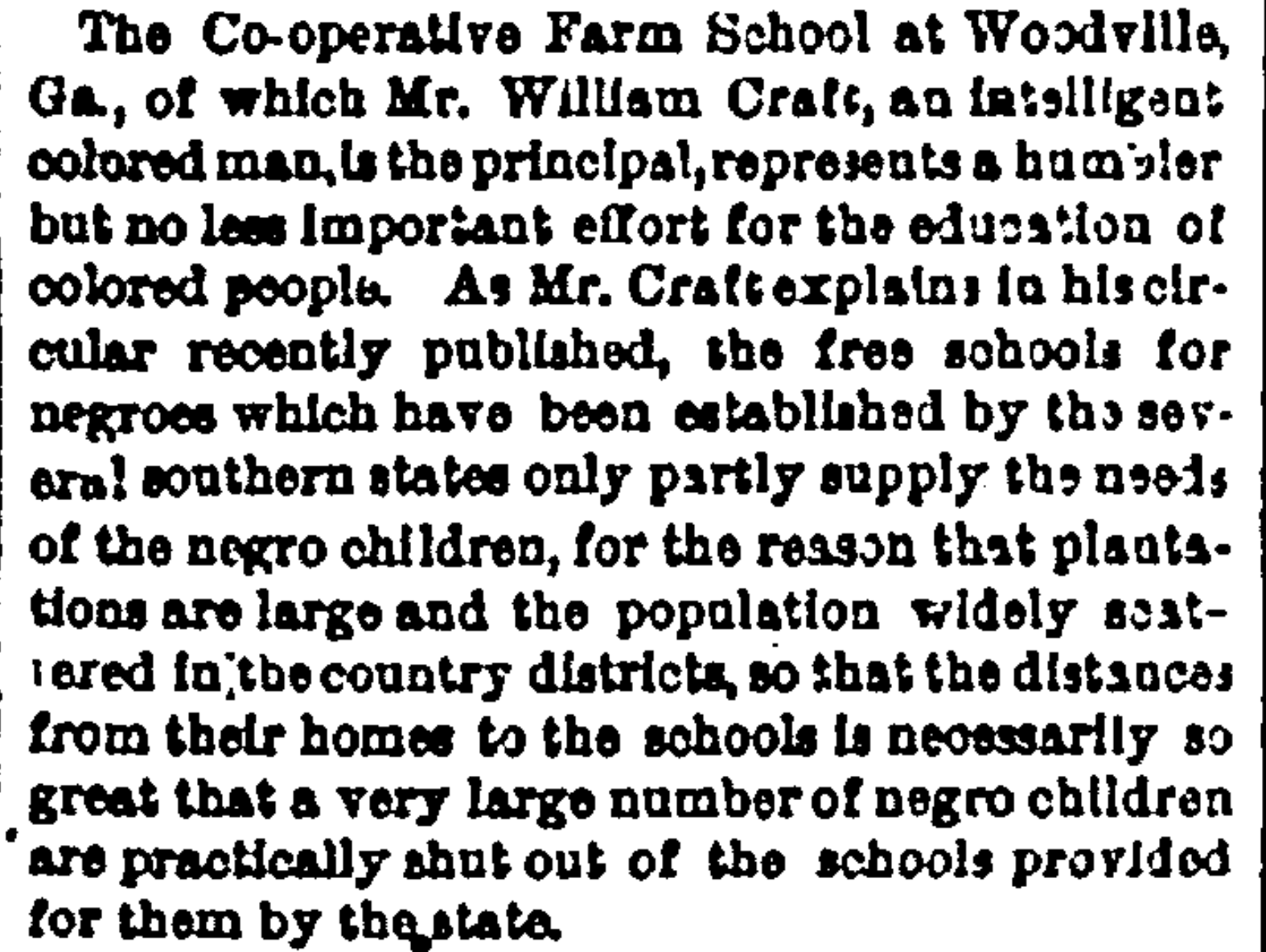

[16] McCaskill, "William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891);" “Two Schools for Negroes,” Evening Post (New York, New York), January 3, 1876, Genealogy Bank; “The Colored School of William and Ellen Crafts” Evening Post (New York, New York), March 21, 1874, Genealogy Bank.

Image: “Two Schools for Negroes,” Evening Post (New York, New York), January 3, 1876.

[17] McCaskill, "William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891);" Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, iii-iv.

Image: Still, Still's Underground Rail Road Records, 368.