Part of a series of articles titled World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska.

Article

World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska - Chapter 4: Killisnoo Herring Plant, pt. 2

Current Condition

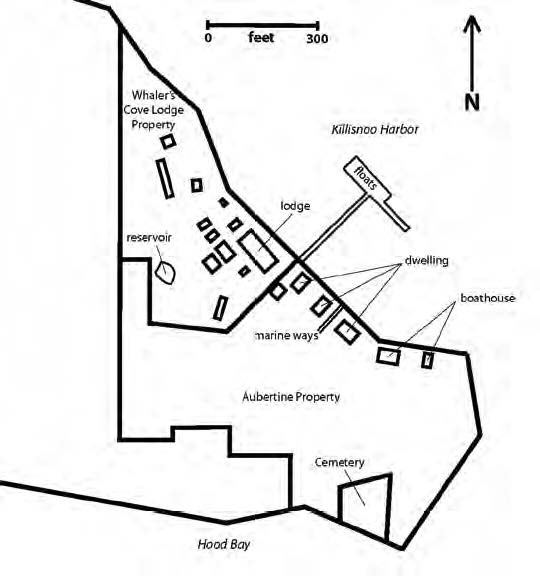

The site of historic Killisnoo is now primarily split between the Whaler’s Cove Lodge and the Aubertine Trust (Figures 117-119). The lodge property extends from the midpoint of the beach fronting Killisnoo Harbor (Figure 118) northwest almost to the point guarding the harbor (Figure 119), where a new cabin has been built on Lot 1N of the Jacobson subdivision. Abutting the lodge property and extending southeast to the opposite point are the home and associated buildings of Tom and Chris Aubertine (Figure 117). Subdivision lots in the interior of the island were not investigated. Evidence of old Killisnoo among the modern developments consists of features on land, features and artifacts in the intertidal zone, archaeological deposits, and artifacts collected for display by the lodge-owners. There are no buildings or even building ruins from old Killisnoo. The old Killisnoo cemetery immediately south of the former industrial area is a separate but related site component (Figure 120).

Modern buildings overlying the historic site of Killisnoo belong to Whaler’s Cove Lodge and the Aubertine Trust. Owner Tom Aubertine was a willing onsite guide (Figure 116), pointing out historic Killisnoo features on his property and the adjacent cemetery. Historic features on the Aubertine parcel were recorded, but buildings in use were not closely inspected. Five buildings are strung out more or less equidistantly along the harbor side of the Aubertine property, consisting of two boathouses and three dwellings. The most easterly building is a small boathouse, not far from where the herring plant’s boathouse was plotted in1891 (Figures 106-107). Next to it is a much larger boathouse (Figure 120); both buildings are sided and roofed in metal. Closer to the lodge are three dwellings in a row: a log cabin, flanked to the northwest by two frame cabins.

The lodge grounds were inspected, as was the second-growth forest along the shore further northwest. Owner Richard Powers authorized access to the lodge property and discussed the building history. Whereas Killisnoo’s three historic use zones along the shore from southeast to northwest were industrial, commercial, and then residential, in 2008 those zones roughly correspond to the Aubertine Trust property, the Whaler’s Cove Lodge facilities, and the second growth forest.

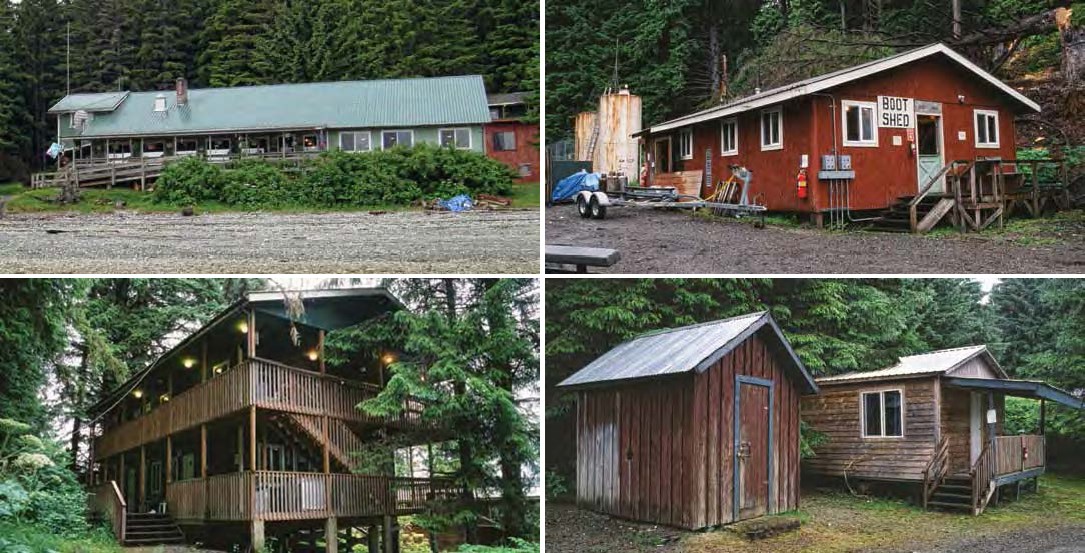

Whaler’s Cove Lodge includes buildings of log, frame, and metal construction, with few unifying architectural themes, reflecting its gradual development as a seasonal fishing resort (Figures 121-125). The largest and most central building is the lodge (Figure 121), with a cafeteria, lounge, kitchen, gift shop, and other spaces. A power house and a shop – two large utility sheds (Figure 122) – are located inland. Other utility sheds, cabins, and two larger residential units are of frame construction (Figures 123-125). All the buildings are built on land above the high tide mark (Figure 126). A floating dock leads to a floating small boat facility, but it is seasonally operated and the floats are stowed on shore for winter.

The boundary of historic Killisnoo (SIT-014) has not been formally defined by archaeological survey, nor was the brief 2008 investigation sufficient to do so. Observations made the length of the shoreline facing Killisnoo Harbor (Figures 117-119) indicate that historic archaeological deposits potentially exist from one end to the other, though recent development has disturbed some areas.

Features on Land

A dense second-growth spruce-hemlock forest covered much of Killisnoo in 2008, reflecting the late 1800s clearing there (Figures 104-105); by the early 1940s the forest was already encroaching upon the facility (Figures 110, 112). Amid the modern forest are patches of bushes and shrubs marking past disturbance footprints (Figure 118), but their meaning is not obvious. Less ambiguous features observed on land were the ruin of a marine ways, the lodge’s current reservoir, and large and/or stationary artifacts.

A linear clearing perpendicular to shore on the Aubertine property represents a marine ways – a track used to haul boats out of the water for storage and repair (Figure 127). The clearing is about 20’ wide and extends from the shore about 60’-80’ into the forest fringe (Figure 120). A gravel track about 8’ wide runs through the center of the alignment. Along the grade to the southeast are the remains of two large plank and plywood cradles mounted on steel railcar chassis. The cradles where they contact the boat hull are upholstered in carpet. Several lengths of regular-gauge rail protrude from beneath the two railcars, and several notched logs are associated with the collection. The condition of the clearing, gravel track, and plywood-and-carpet cradles suggested manufacture and operation decades ago. Owners Aubertine and Powers stated that the system included 4-5 rails salvaged from the Kanalku coal mine on Admiralty Island combined with rails and cars from a mine in Idaho, installed at Killisnoo long after World War II by Carl A. Jacobson, Jr., and Powers himself. The track and gear have not been used since the early 1990s.

In 1891 Killisnoo had a reservoir plotted on USS 5 midway between the school (labeled “S.H.” in the upper left of Figure 107) and church (Figure 106). The island’s feeble seeps were channeled to it by way of intersecting ditches, some over four feet deep to bedrock, according to historic photographs. The ditch and reservoir system and a creek across Killisnoo Harbor (requiring a boat to access) were used by Atka villagers as water sources (Kohlhoff 1995:120). A secondary reservoir about 150’ south of the one plotted in 1891 (Figure 107) must have been in use by then, as such a feature was enlarged by Richard Powers to serve the lodge. In 2008 a grassy embankment retained a small pond of dark water, backed up to a few spruce and hemlock trees (Figure 128). Water retention has been improved with a black pond liner. Evidence of the reservoir’s historic origins was lacking.

At least eight boilers were observed in the former Killisnoo industrial area. Three (Figure 129) are located just inside the treeline immediately next to one of the boathouses on the Aubertine property. Another five or six boilers were found another 30’ further inside the treeline (Figure 130). The large artifacts are rusty and overgrown with vegetation, and appear to have not moved for decades.

Several rusty artifacts from the herring plant have been moved and landscaped into the grounds of the lodge, but only one large stationary machine was noted in its original position. Located near the boundary of the lodge and Aubertine properties is a steam engine on a concrete pedestal, mounted with the power shaft parallel to the shore (Figure 131).

Intertidal Features and Artifacts

Killisnoo’s intertidal zone was not extensively inspected in 2008. Piling stubs ground flush and buried beneath the beach gravels are likely present offshore, as are isolated artifacts, and local resident Frank Sharp as well as Richard Powers mentioned sport divers bringing up historic artifacts from the harbor where the dock was located. But the only features recorded in 2008 consisted of an extensive scatter of industrial debris on a long reef marking the southeast end of the beach (Figures 132-133), and a pair of pilings.

Within the reef scatter are remains of two boilers, cable, chain, pulleys and gears, vehicle axles and tire rims, barrel hoops and other sheet metal items, angle iron, pipe and wire in various diameters, and some glass and ceramic items. Metals represented include iron/steel, copper, brass, and lead alloys. The scatter shows in a 1945 photograph of the Aleut departure (Figure 112), so it holds more than 65 years of antiquity. Industrial debris from Killisnoo has been discarded there into recent decades, according to Tom Aubertine.

The pair of pilings consists of one at the vegetation line onshore and another about 20’ offshore perpendicular from it, approximately 80’ southeast of the marine ways. Tom Aubertine believes these mark the former location of Killisnoo’s original historic marine ways.

Terrestrial Archaeological Deposits

Several localities within the current resort have disturbances revealing black organic deposits and historic artifacts. Intact deposits revealed by natural exposures (primarily the rootwads of fallen trees), were observed in two places. The most extensive evidence is northwest of the resort where the historic village of Killisnoo was destroyed by the 1928 fire. Large metal artifacts like stove parts protrude through the forest floor. Smaller artifacts noted on the surface included leather and ceramic items (Figures 134-135), as well as enamelware utensils. Second-growth timber covers most of the area and the sod and moss were sufficient to hide most cultural features, but clam shell clusters showed in several places. Bits of rotten planks could be discerned – sometimes in isolation and sometimes in clusters defining a building footprint. Near the far northwest end are several concentrations of rotten planks from buildings that either escaped the 1928 fire or were built later.

The second deposit of archaeological interest is an exposure of densely packed shell less than 50’ inland from the old marine ways (Figure 136). Overlying the shell and worked into it was a layer of crusty black bunker fuel visible in 2008; since then bioremediation has almost totally removed the oil, according to Richard Powers.

Scavenged Artifacts

In addition to a few large industrial artifacts landscaped into the grounds for the enjoyment of lodge patrons, smaller artifacts have been collected for display. Arranged on the southeast exterior wall of the lodge is a collection of firearm parts – mostly metal barrels and actions – recovered during lodge development (Figure 137). One specimen has a fire-warped barrel, and the sheer number of specimens (at least 30 on display) attests to the speed of the 1928 fire – people had no time to salvage essential items such as shotguns and rifles.

Almost as useful were the large saws needed not only to provide firewood for domestic use but to cut the large quantities of industrial boiler cordwood. As with the firearms, the large number recovered and displayed at Killisnoo gives a sense not only of how common the tool was in the typical Killisnoo household but also of the speed of the fire that prevented their owners from saving them. A one-story frame cabin immediately southeast of the lodge, named the Hasselborg Cabin after one of Admiralty Island’s notable historic characters (Orth 1967:409), has its entrance flanked by saw blades (Figures 138-139).

Last updated: February 14, 2021