Part of a series of articles titled World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska.

Article

World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska - Chapter 5: Wrangell Institute

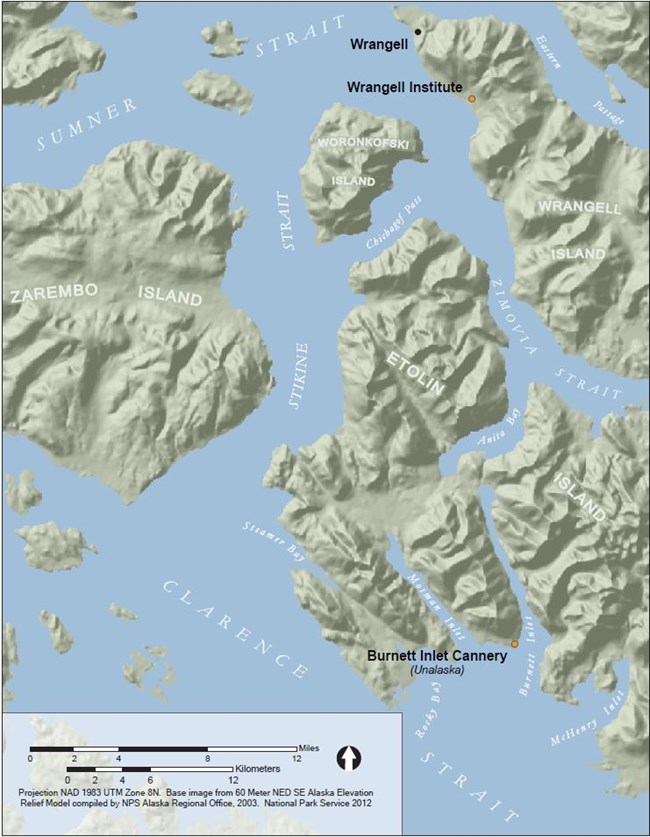

While Aleuts from Atka and the Pribilof Islands were taken directly to their wartime camps, the others were housed during late summer of 1942 in a tent city on the grounds of the Wrangell Institute – a large territorial boarding school on Wrangell Island near the town of Wrangell – until facilities at the Burnett Inlet cannery and Ward Lake CCC camp were readied. Like its neighbors, Wrangell Island is mountainous and cloaked in deep forest (Figure 147). At Wrangell the huge outflow of the Stikine River meets the deep channels of Frederick Sound, Sumner Strait, Stikine Strait, Zimovia Strait, and Eastern Passage radiating out like spokes on a wheel (Figure 148), supporting a rich marine life. In the early 1800s the availability of sea otter and other furs encouraged the Hudson Bay Company and Russian American Company to develop posts for trading with the local Tlingit. The town of Wrangell survived to become one of southeast Alaska’s few population centers, cyclically relying on furs, fishing, mining, logging, and tourism during the 1900s and into the subsequent millennium.

Early Years

By the 1930s Alaska had a history of church- and government-sponsored Native boarding schools and orphanages at Sitka, Eklutna, Seward, Holy Cross, Unalaska, Kanatak (in Bristol Bay), and elsewhere. The Territorial Commissioner of Education had announced the intention to build an industrial school in southeast Alaska as early as 1924 (Parks 1932:95). In October of 1932 the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs began classes at the new Wrangell Institute, a large complex overlooking Shoemaker Bay several miles south of Wrangell (Figures 148-149). The school was described as “one of the pet projects of the Roosevelt Administration” (Yzermans 1979:55). An appropriation of $171,000 was made to clear the land and erect the first five buildings (Parks 1932:95).

Initial enrollment consisted of 71 high school students drawn mostly from southeast Alaska. Students were expected to obtain a vocational education, and school maintenance tasks formed part of the instruction. Home building, nursing, commercial fishing, and home economics were among the list of trades taught (MacPherson 1998a). In 1937, prior to his 1941 appointment as Curator of the Alaska Territorial Library and Museum (a position he held until 1965), Edward L. Keithahn began teaching at the Wrangell Institute (Alaska State Library 1996). He authored articles and books on Alaska topics including totem poles (Keithahn 1945), and supervised the student-carved totem poles that can be seen in early photographs of the school ( Jordan 1966). Though ostensibly not affiliated with any religious organization, Wrangell’s Catholic priest took an interest in the school and incorporated it into his parish (Yzermans 1979:55-56).

National Archives Pacific Alaska Region RG75 (BIA) Box 14 4/8/8(3)

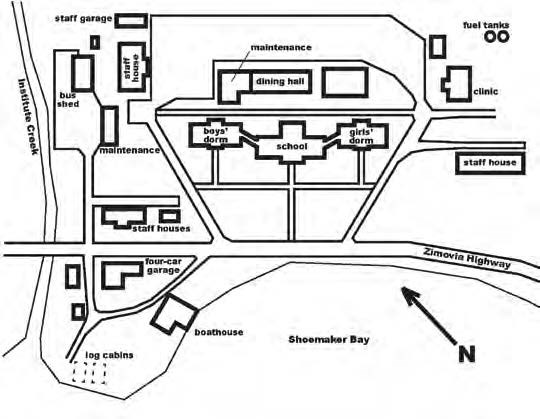

The size of the Wrangell Institute’s land parcel has been reported as 171 acres or 141 acres (MacPherson 1994,1998a), with development concentrated in a cleared rectangle measuring approximately 1000’ x 500’ (Figure 149). Centrally located was a large school building connected by enclosed walkways to large flanking two-story dormitories – boys on the left (northwest), girls on the right (southeast). With the school measuring 110’ long, the dormitories 144’ long, and the walkways spanning about 30’ between the buildings, the enclosed space was over 450’ long. Other buildings bounded large rectangular yards and parking lots; and eventually driveways, sidewalks, and terraces added more geometry and symmetry to the plan (Figure 150). Reports compiled in 1944 by the federal government describe a compact campus with about a dozen significant buildings. Most of the building materials were standardized: walls of 2”x 6” studs, shiplap, with stucco on the outside surface and metal lath and plaster (or plasterboard) on the inside surface; roofs of 2” x 8” rafters overlain with shiplap and asphalt shingles; and 2” x 14” joists for the basement floor and 2” x 10” joists for the first and second floors, overlaid by shiplap and 1” x 4” hardwood flooring.

The school building was a 17,620 square-foot, two-story building with a half-basement, and a one-and-onehalf story flat-roofed gymnasium on a concrete pad centrally attached to the back of the building. The main building had a simple hipped roof with a central bell tower (Figure 149); a central cross-hipped entrance block with three arched penetrations and a central entry facing the waterfront. Three oil-fired boilers in the basement provided steam heat to radiators in the school and adjacent dormitories. The basement also contained two shops. The first floor held four classrooms, two offices, and the gymnasium, while the second floor held four more classrooms, an assembly room, and a library. When inventoried in 1944 the school building had drinking fountains in the halls but no bathrooms – likely bathrooms in the boys and girls dormitories were relied upon. The girls and boys dormitories were built from the same plans as mirror images of each other, attached to the school by covered walkways with arches matching those of the school and dormitory entrances (Figure 149). Like the school, the dormitories had two stories, but the girls dormitory had only a partial basement and the boys had none at all. Like the school, they had a simple hipped roof with a central cross-hipped entrance block and arches facing the waterfront. The first floor of the girls dormitory contained a kitchen, a separate dining room, a social room, and “two rooms used for sewing and cooking classes,” according to the property inventory form. On the second floor were two large dormitory rooms, a bathroom, two private rooms, and a three-room apartment for the girls dormitory supervisor. The first floor of the boys dormitory contained a laundry, two social rooms, a bathroom, and three private rooms, while the second floor held two large dormitory rooms, storage rooms, and a three-room apartment for the boys dormitory supervisor. Unique to the boys dormitory was a “smoking room” on the second floor. Each of the dormitories contained more than 12,500 square feet of space, housing a maximum of 96 boys and 83 girls.

All photos: National Archives Pacific Alaska Region RG75 (BIA) Box 14 4/8/8(3)

Some Wrangell Institute teachers and employees lived in Wrangell and commuted to work, but others lived on the grounds in a ten-unit apartment complex at the north end of the clearing (Figure 151). The staff house was a two-story building with a partial basement containing a laundry room and the oil-fired boiler for the steam heating system. Two- and three-room units were available, and the lobby was designed as a social area. The building contained over 3,000 square feet of space. The apartment’s architecture matched the school and dormitories, with a hipped roof and a central cross-hipped entrance block with three arches.

The medical clinic was completed in 1932, a year after the school, dormitories, and staff house were built. It was a one-story building with a basement and attic apartment at the south end of the clearing. The building’s hipped roof and central cross-gabled entrance block with three arches matched the architectural details of its companions. The side opposing the entrance also had a cross-gabled block and a rear entrance, and the roof had a small shed-roofed dormer (Figure 152). The small basement held an oil-fired boiler for the steam heat system, while the first floor contained a clinic and five small wards, a “diet kitchen,” an office, a room for the attendant, and three bathrooms. The nurse lived in an attic apartment with a living room, kitchen, and bathroom.

In 1934 the school built a vehicle garage, and the following year they built two more. The first was a one-story L-shaped building constructed on the shore side of the highway, with four enclosed bays facing the campus (Figure 153); another two open bays were added on the shore side (facing Shoemaker Bay) in 1936 (Figure 150). Students and staff made the building with a hipped roof to match the other buildings, and poured two concrete grease pits into the floor. The original building measured 20’ x 43’, while the addition measured 20’ x 23’. One of the two garages built in 1935 was also a four-car design with a hipped roof, open bays, and a shop area, with the addition of a gasoline pump and a 500-gallon fuel tank, lubrication oil dispensers, and an air compressor (Figure 154). The building measured 20’ x 45’, or 900 square feet. It was situated near the large staff apartment and intended to house staff vehicles. The second 1935 garage was a small 11’ x 18’one-story building with a hipped roof.

All photos: National Archives Pacific Alaska Region RG75 (BIA) Box 14 4/8/8(3)

The ten-unit apartment building was not the only staff housing available by World War II. In the late 1930s the CCC began construction of two 22’ x 30’ log cabins behind the six-car garage, near the shore (Figures 155-156). Left uncompleted by the CCC,one was finished by students and staff in 1941 and the other in 1942. Each cabin contained a living room, kitchen,bedroom, and bathroom, and was heated by a wood stove. The main gabled roof was complemented by shed roofs over a door at each gable end.

At the water’s edge students and staff built a 20’ x 60’ boathouse on a concrete foundation, where vessels could be winched for repair and storage using a 40’ marine ways (Figure 157). Archival photographs indicate construction in 1938. Shiplap siding protected the exterior walls, and asphalt shingles protected the roof. The large bay facing the water had tall plank doors to keep out the elements, but a shed-roofed extension of posts and trusses on the north side of the building was left open (Figure 158). Rather than following the lead of the Sheldon Jackson boarding school in Sitka,which had its own fishing boat to help feed the campus, the Institute built watercraft rigged solely for transportation, according to Richard Stokes.

National Archives Pacific Alaska Region RG75 (BIA) Box 14 4/8/8(3)

Simple wooden boats named Institute 1 through 3 reached lengths of 40’ (Figure 159). By 1942 the CCC had completed a dock and floats for the school (The Wrangell Sentinel 1942a).

The 1944 property inventory listed several other campus features, including a small building to house fire hose, and the two 20,000 gallon oil tanks and pumphouse that served the individual buildings (Figure 160). Near the waterfront staff and students also built an open fish-cleaning station in the Adirondack style, with cedar shakes on spruce poles and a concrete slab foundation (Figure 161). Nearby was an elevated smokehouse of similar construction, with “plank catwalks for hanging fish” (Figure 162). The 1944 inventory also includes photographs of a timber dam approximately 15’ high and perhaps 40’ long – probably constructed northeast of the campus up Institute Creek and used to collect domestic water. As the 1944 photographs illustrate, unlike the other locations where Aleut evacuees found themselves, the Wrangell Institute was a fully-functioning federal facility at the beginning of World War II.

All photos: National Archives Pacific Alaska Region RG75 (BIA) Box 14 4/8/8(3)

Top left: National Archives Still Picture Branch; Bottom left: Alaska State Library Butler/Dale collection PCA306.2266; Right: National Archives Still Picture Branch

World War II and the Camp Experience

The Aleut experience at the Wrangell Institute was of two kinds. Villagers from Unalaska, Nikolski, Makushin, Akutan, and Kashega arrived there directly as fresh evacuees from the Aleutian Islands before being forwarded to their ultimate wartime destination (Figure 163). Then, after being settled in their camps, children from the relocated villages were sent to the Wrangell Institute for schooling.

The Alaska Steamship Company’s vessel SS Columbia arrived at Wrangell Institute on July 13,1942, to deliver 160 Aleuts into the custody of the Alaska Indian Service – the U.S. Department of the Interior’s agency for administering Native affairs in the territory. The six-village contingent consisted of 41 people from Akutan, 18 from Biorka, 20 from Kashega, eight from Makushin, 72 from Nikolski, and one from Unalaska (Kohlhoff 1995:80-81). Military and political matters delayed evacuation of Unalaska, and reports differ on the event details. On August 1,1942, 137 Unalaskans arrived at Wrangell Institute on board the Alaska Steamship Company’s vessel SS Alaska according to Kohlhoff (1995:84), while Kirtland and Coffin (1981:35) state that 111 Unalaskans arrived there on July 26 – one week earlier.

The Juneau office of the Alaska Indian Service began making arrangements in mid-July to receive Aleut evacuees at the Wrangell Institute (Kohlhoff 1995:80). The broad terraced grounds were to become a temporary city. More than twenty large pyramidal military tents were erected along the existing sidewalks, each on its own tent platform (Figures 163-165). The entry of each tent faced southwest, towards the sidewalk and the beach beyond. Each tent was equipped with a small camp stove – photographs show both sheet-metal and cast types – stationed in a long row outside the tents on the opposite side of the sidewalk. Obviously used for cooking rather than heating, the stoves’ locations indicate a concern for fire danger among the closely packed dwellings. Canvas patches are visible on some tents. According to one evacuee, women and children were assigned to live in tents (Figure 165), eight per tent, with one cot per tent, while men and boys slept in the vacant dormitories (Kohlhoff 1995:101). The Wrangell Institute tent camp was intended to be struck in the fall of 1942, after better accommodations were readied elsewhere (and before returning students arrived to begin the new school year). Villagers from Unalaska spent less than a month there before moving to the cannery at Burnett Inlet (Kirtland and Coffin 1981:35). Villagers from Akutan, Biorka, Kashega, Makushin, and Nikolski built a barge (probably using the Institute’s boathouse) that was then filled with building supplies and towed to Ketchikan by the USS Penguin in late August (some remember an Institute vessel pulling the barge); 25 villagers accompanied the barge while the remainder traveled to Ketchikan on-board an Army transport vessel (Kohlhoff 1995:103-104).

By early September the tent camp was gone and the Wrangell Institute started its regular school year, beginning the 1942 fall enrollment with an unprecedented number of Aleut students. Lee McMillan’s log at Funter Bay recorded the USFWS’s Brant leaving October 17 for the Institute, bringing 20 Pribilof Islands schoolchildren, their two schoolteachers, and the schoolteachers’ children, and the children were also enrolled the following year (Kirtland and Coffin 1981:62). Children from other evacuation camps also attended school at the Wrangell Institute (Kirtland and Coffin 1981:63), but “the record of enrollment of children from Killisnoo, Ward Cove and Burnett Inlet has not been discovered.”

Last updated: February 14, 2021