Part of a series of articles titled World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska.

Article

World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska - Chapter 4: Killisnoo Herring Plant, pt. 1

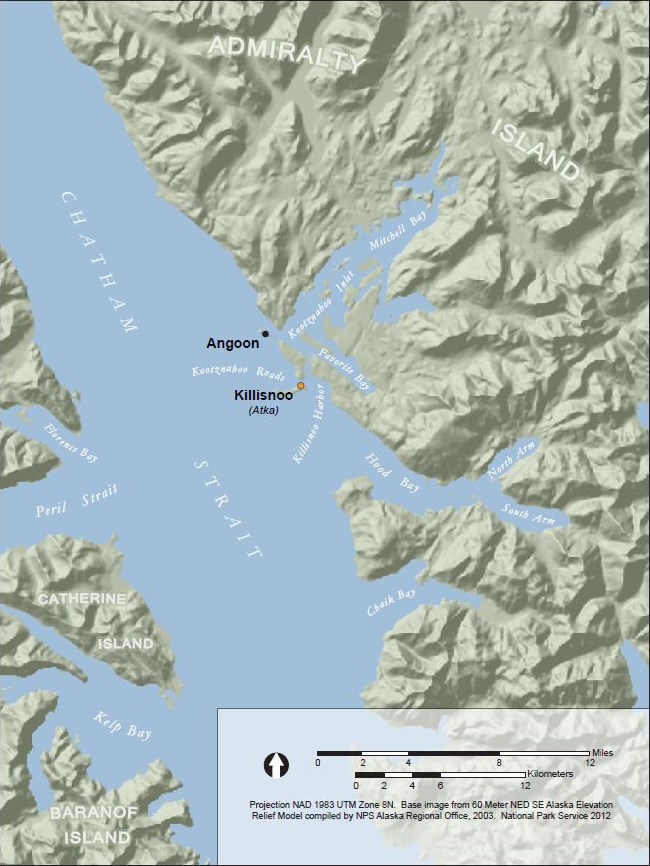

Villagers from Atka were housed during the war in the defunct herring factory at Killisnoo, near Angoon (Figure 102). Over 50 miles south of Funter Bay on the west side of Admiralty Island is a rich marine environment where the mouths of Mitchell Bay, Hood Bay, and Chaik Bay look across Chatham Strait at the entrance to Peril Strait (Figure 103). The lushly forested hills and mountains enclose many streams with large salmon runs. In the 1800s herring were plentiful and had long been a traditional staple of the local Tlingit Indians. Humpback whales plied the waters of Chatham Strait, preying on krill, herring, and other marine species. The rich marine resources attracted the attention of the Northwest Trading Company, which in 1878 established a station on the island of Killisnoo (Figure 103), near the Tlingit village of Angoon (de Laguna 1960:49). The Killisnoo herring plant was one of American Alaska’s first industrial enterprises.

Early Years

The company constructed extensive wharf and warehouse facilities (Figure 104), began rendering herring oil and processing the fish waste into fertilizer – then called “guano” in reference to bat dung – in 1879, and began a whaling station the following year (de Laguna 1960:162). Native men from nearby Angoon were employed in the commercial whaling operation, leading to an infamous matter in 1882 involving Killisnoo, Angoon, and the U.S. Navy. Bare facts of the incident are that: a whaling gun exploded, killing a shaman employed on the boat, leading to a work strike by the Natives and the demand of restitution (the condition for return to the company of their whaling boat and two non-Native employees), scaring the non-Natives at Killisnoo, who contacted the U.S. Navy, which responded with several vessels armed with howitzers and gatling guns, culminating in the shelling of Angoon and its villagers, the burning of the village and 40 dugout canoes, and resulting Native deaths (Reckley 1982).

Left: Alaska State Library Vincent Soboleff collection PCA1-243. Right: Courtesy of Richard Powers, Whaler’s Cove Lodge.

Seasonal Native settlement was subsequently encouraged at Killisnoo, and soon a dense cluster of Native houses, sheds, and smokehouses formed northwest of the commercial buildings (Figures 104-105). The local Tlingit joined a multicultural workforce of Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, and Swedes that lived year-round at Killisnoo.

Killisnoo became one of the first federally surveyed tracts in the Alaska Territory when U.S. Deputy Surveyor Charles W. Gorside mapped the facility in 1891 as USS 5 – the “Trading and Manufacturing Site” of the Alaska Oil and Guano Company (Figures 106-107). At that time a collection of about 40 “Indian Huts” at the northwest end of the site housed the families of the local Native work force. On the hillside south of those buildings was the territorial school, then a small reservoir, and south of the reservoir was the Russian Orthodox church and a fenced churchyard. Downslope from the church, at the water’s edge, was a supply house and the agent’s house. Southeast of the church were a group of buildings labeled in 1891 as “Russian Houses.” Between those buildings and the shore were five small buildings, plus two small covered wells, and at the high tide line were two larger buildings of which one was the company store. Moving southeast along the shoreline from the store there was a gap of about 75’ before the large industrial buildings of the plant began. Archival photographs show Killisnoo to be almost completely deforested by the late 1800s, with less than a dozen tall old-growth trees left standing.

An enlargement of the 1891 plat shows the array of industrial facilities at the Killisnoo plant (Figure 107). Prominent was a wharf perpendicular to the shore, extending 300’ into Killisnoo Harbor. As the wharf approached the shore it broadened to create – including buildings – a work/storage space measuring more than 100’ x 150’ on pilings over the inter-tidal zone. At the shore end of the wharf was a boiler room on land, attached at one corner to a large building partly over the intertidal zone labeled “Factory.” At the northeast corner of the complex was a “press house” and a “salting house.” At the southeast corner was the cooperage, or barrel-making shop, and a building labeled “Day H.” – perhaps the crew mess hall. Scattered among these buildings were four others labeled “Guano H.,” where product in various stages of manufacture was stored. Continuing southeast along the shore from the factory complex were a small smoke house, a barrel storage yard, and a boathouse (Figure 107). At its zenith the Killisnoo herring plant was one of Alaska’s largest industrial enterprises, with a bustling harbor and even a steam whistle to call the crews to work.

Killisnoo continued in operation in some form through the following decades, processing herring, whales, and sometimes other marine products. In 1928 almost all of the housing burned to the ground, leaving only the industrial plant and a few nearby commercial/industrial buildings (de Laguna 1960:49). The story is told secondhand by Richard Powers that the fire began in a smokehouse when two small children, instructed to watch the smokehouse and not leave it under any circumstances, did as they were told and stood watching as the building caught fire and spread to the village. The effects were soon felt. The post office was shut down in 1930 after 48 years of operation (Ricks 1965). Census takers in 1930 found in the former community of Killisnoo, which had for 40 years a population of around 300 people, only three people (Orth 1967:519). After the fire the Tlingit work force moved back to Angoon, and the nearby cannery at Hood Bay became their primary source of income (Mobley 1999:13-44). Frederica de Laguna (1960:49) reports that prior to 1942 the Admiralty Island side of the channel across from Killisnoo (both sides of the channel were collectively called Killisnoo by the Tlingit) was home to a group of Japanese men who were subsequently interned elsewhere for the duration of World War II.

Last updated: February 14, 2021