Part of a series of articles titled World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska.

Article

World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska - Chapter 3: Funter Bay Mine, pt. 2

Current Condition

Compared to the five other WW II Aleut relocation camps, where most buildings have been razed or removed, most of the Funter Bay mine buildings have decayed in place. Thus its remains are the most evocative of the six sites. Inland are the mine workings and equipment, while the shoreline holds the mine camp that had been occupied by St. George villagers. The buildings described here as “standing”are those with effective roofs making them usable; those described as ruins may have one or more standing walls but are nonetheless well on their way to becoming archaeological features. Other features are grouped for discussion according to whether they are along the shoreline (part of the mining camp) or inland (part of the mine workings). Alaska Tidelands Survey 712, made in 1970, plots the buildings evident at that time and forms a good base map for describing the 2008 circumstances (Figure 72).

Standing Buildings

Standing buildings at the Admiralty Alaska Gold Mine include a modern prefabricated metal utility shed, historic Building T that has been remodeled into a home, the two-story bunkhouse (Building L), a small shop (Building M), and three small sheds. The prefabricated building has an arched roof and walls made of windowless metal panels with ribbed joints, with a vehicle entrance at one end (Figure 73). The building was erected 20’-30’ from shore at the south end of the site in about 2005. Other storage sheds consist of two small gable-roofed buildings clad in T-111 serving Building T, and an older (but not wartime) gable-roofed shed immediately southwest of the Quonset hut. The latter building is sided and roofed with corrugated metal sheeting, and is windowless (Figure 74).

The only other new construction at the site since the Aleut experience is a frame addition to Building T, the Funter Bay residence of Sam Pekovich, who caretakes the site on behalf of the Admiralty Alaska Gold Mining Company. The composite building is an attractive one-story dwelling with the addition’s north gable end attached to Building T’s south gable end (Figure 75). Both components have a metal roof. The addition is clad with T-111, while the original building is unclad and has nail-stains on the weathered horizontal boards that show the stud patterns.The older building has an enclosed entry facing the water and another facing inland, each with a simple plank exterior door. Both front and back doors are original wartime fixtures (compare Figures 62 and 76). Whereas the building once had only six-pane fixed windows (Figure 62), now all but two in the front entry have been replaced with single-pane windows (Figures 75-76).

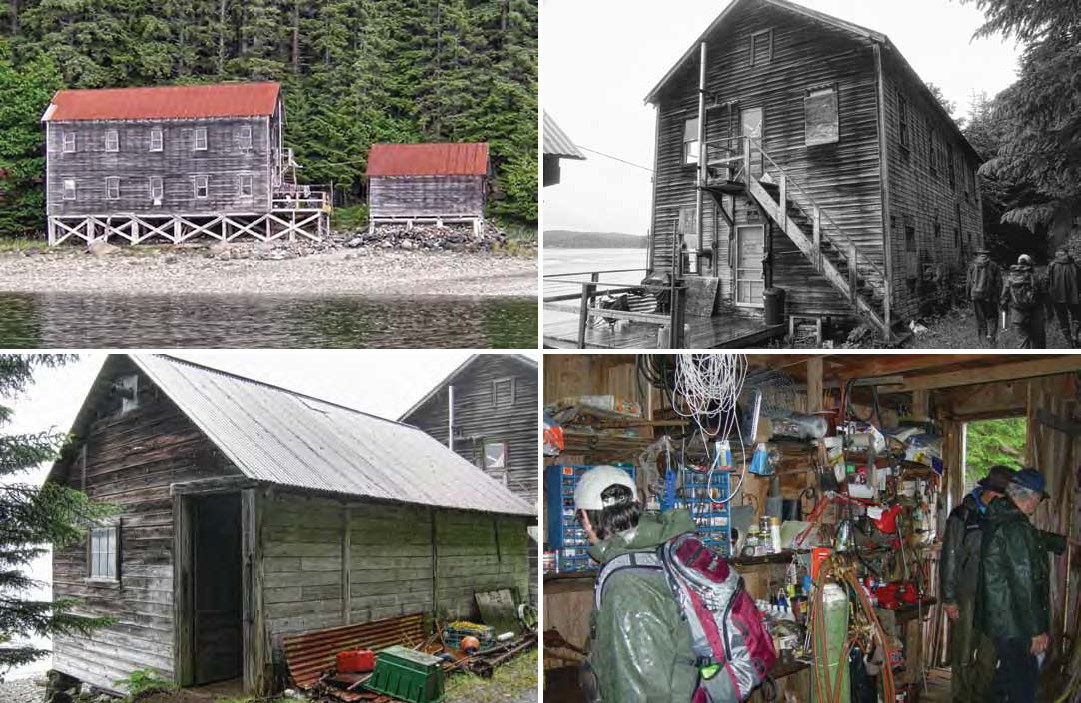

Standing side-by-side as a conspicuous part of Funter Bay’s built environment are the mine’s original two-story bunkhouse and warehouse/ shop (Figure 77). The bunkhouse (Building L) is a simple wood frame gable-roofed building on pilings over the upper intertidal zone. Five equidistantly spaced windows penetrate the east and west eave elevations on both floors to create two long identical parallel walls. Each gable end has symmetrically spaced windows upstairs and downstairs, with a door centered on each floor of the south elevation (Figure 78). The north elevation has no doors. The interior was not inspected, but the building style is typical of simple two-story bunkhouses built by canneries and mines in southeast Alaska, with its long axis parallel to shore (Mobley 1993:34-41, 1999:1625; 2009:42). The building’s materials consist of drop siding, red-painted corrugated metal roofing, and 1/1 sashed windows replacing original 6/6 sashed units. Most of the north- and east-facing windows are boarded over. The south gable end has exterior stairs to the second floor and a stovepipe from the first floor up to the roofline (Figure 78). In 2008 the building was inhabited, and has been sporadically for the last couple decades, according to Sam Pekovich.

Immediately south of the two-story bunkhouse (Figure 77) is original Building M. The building is of the same materials as the bunkhouse, with dilapidated drop siding, red-painted corrugated roofing, and a single six-paned window penetrating the south gable wall (Figure 79). It still functions as a warehouse/shop as it did 70 years ago (Figure 80).

Building Ruins

Classed as ruins are buildings ranging from those with deteriorated roofs, walls, and/or foundations making them too dilapidated to be of use, to buildings consisting of little more than rotten boards protruding from the forest floor.

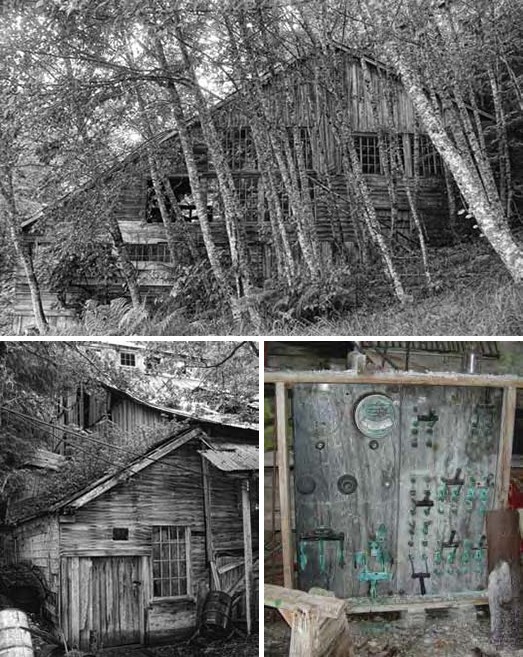

The most prominent ruin in 2008 was the mill (Building Q), a large wood frame building with several floor levels and roof angles (Figure 81). Though its walls and roof appeared relatively intact during the field investigation,the building’s interior was a dangerous jumble of collapsed beams and equipment that precluded anything more than a glimpse from inside one door. According to Sam Pekovich, snow collapsed the building during the winter of 2008-2009. Construction materials consisted of 12” x 12” posts and beams, 2” x 12” planks, and smaller lumber.The majority of the building’s window frames were in place and more than half the glazing was intact, with most windows – including a massive bank on the south elevation – being fixed 16-pane examples (Figures 81-82). Some of the building’s siding was of vertical planks, and some were horizontal (Figure 82).

The 100-hp diesel engines mentioned by Chipperfield (1935) were still in place in 2008, on the bottom floor midway along the south wall. A large Westinghouse switchboard with copper breakers remained in the building (Figure 83). A large metal lathe and drill press were positioned in the southwest corner of the building. Visible from the building’s southwest corner door was an ore hopper on the second level. An ore elevator visible through a window had its manufacturer stenciled on the side: “J. Jacob Shannon & Co., Pasadena, N.J.” (internet references indicate the firm was a prominent farm and mine equipment manufacturer based in Philadelphia in the early 1900s).

Two small cabins shifting into the ruin category are similar in design. Each is a single-story frame building with gable walls perpendicular to the shore and a shed-roofed entry facing south (Figures 84-85). One of the two (Building A) has a second shed-roofed room on its north end (Figure 84). Each of the cabins has vertical plank siding, corrugated metal roofing, and windows with four and six panes. The second of the two cabins (Building J) still shows remnants of red paint (Figure 85). Building A’s interior (Figure 86) is similar to that of Building J, with tattered beaverboard walls and ceilings. Its domestic function is evidenced by a derelict wood stove, a built-in ironing board, a wire-chain-spring bed frame, and a kitchen with counter space and pantry shelves.

Plotted as Building N in 1942 is a one-story building variously used as a residence and an office. The building is of frame construction with drop siding and a corrugated metal roof (Figure 87). The roofing metal – which appears to be only a few decades old – is too short, and rotten wood shingles protrude from under it at the eaves. A roof extension protects a small entry centered on the wall facing the waterfront. The entry has a five-panel wood door and a four-pane window; other windows are 1/1 sashed examples.

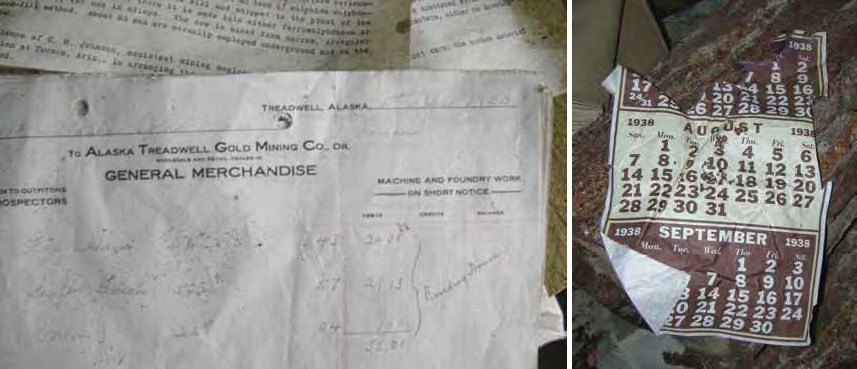

During the Aleut experience the main approach to the mine was by way of the north dock (Figure 58), which disembarked passengers to the tramway/boardwalk running the length of the camp and deposited them before three buildings in a row. Remains of the three – Buildings B, C, and D – were easily distinguishable in 2008. Building B is a shed-roofed building with vertical plank siding and a decided list away from the water due to foundation failure (Figure 88). The porch upon which federal officials were photographed in 1942 (Figure 65) is no longer evident. During the internment Father Feodosiy lived in the building (Figure 66). The 1970 map (Figure 72) labels it “store building,” meaning either a warehouse or a commercial retail establishment – both are logical functions given its position at the foot of the dock. The building floor holds a jumble of documents that predate World War II (Figure 89). Ore reports and similar mining documents are mixed with other scraps of paper. A receipt dated December 1, 1920, from the company store at the Treadwell Mine in Juneau, lists the purchase of 56 lbs. of ham, 52 lbs. of bacon, and 25 lbs. of onions (Figure 90). A calendar displaying the months of July, August, and September was dated 1938 (Figure 91).

Immediately south of Building B are the remains of Buildings C and D – a pair of pyramidal hip-roofed residences that stand out from the mining camp’s other gable-roofed buildings (Figure 58). Both have failing foundations, roofs, and walls, and both are being reclaimed by forest vegetation (Figure 92). The 1942 map (Figure 59) says Building D was “used as hospital,” but nothing inside would suggest that function.

The wash house built in late 1942 for St. George villagers (Figure 70) is slumping into the intertidal zone north of the two-story bunkhouse. The one-story frame building’s foundation is giving way, and the north end is little more than a jumble of boards, but the south end is more intact (Figure 93). The building still displays evidence of its six-pane windows, drop siding, and five-panel wood doors, and inside a few shelves and other furnishings can be seen (Figure 94).

Another ruin of a building constructed during the war is on a bench upslope, or east, of the boardwalk alignment.Building U is listed on the 1942 map (Figure 59) as a new six-family dwelling with six contiguous rooms. In 2008 it consisted of a wide rectangular swathe of planks embedded in the forest floor (Figure 95). Here and there a window or door frame can be seen, and obviously the roof collapsed in place, but few structural details can be discerned. Furniture fragments or artifacts were lacking. The 1942 archival photograph (Figure 69) relays more immediate information about the building’s appearance than does its archaeological context.

One Quonset hut is located along the waterfront side of the shoreline tramway/boardwalk, between Building M (Figure 74) and a post-war corrugated utility shed. The exterior wooden partitions at each end are badly deteriorated, and the building leans to the north (Figure 96). It was used mostly for firewood storage in 2008.

Shoreline Features

A pedestrian at the mining camp in 2008 could not help but notice the long path, some of which is graveled for vehicle traffic, along the waterfront between the buildings and ruins (Figure 97). The path is the current reflection of the wartime boardwalk and tram track (Figures 59, 65, 72). Rails for the tramway have been removed from the camp, but eventually they reappear on the inland section leading to an aerial tram station.

Another feature evident in 2008 is a large steel oil tank located upslope from the boardwalk (Figure 72). The tank is about 18’ in diameter and 12’ high, with a prominently beveled upper rim. According to Sam Pekovich, the tank postdates World War II and is unused. A second tank is stored in pieces nearby.

Parts of two historic water systems were observed in 2008. One feature consists of a simple 2” steel pipe conducting water to a tap in the north part of the camp from a small spring upslope. The second system is evidenced by a small rectangular plank and sheet metal box or dam buried in a creekbed upslope from the mill, that once diverted water into a pipe and on to the camp. Though not labeled, the feature is drawn on the 1942 map as serving two toilets at the high tide mark (Figure 59). Sam Pekovich described a 3’ diameter pipe that once extended from the dam to the mill.

Suggested by only a few rotten boardsin 2008 was the stairway leading up the mountainside from the boardwalk to the six-room bunkhouse (Figure 72). Since the bunkhouse (Building U) was built for Aleut use in 1942, the stairway was likely built then, too. The uppermost portion of it shows in an archival photograph (Figure 69).

Artifact scatters around the mining camp reflect the accumulation, storage, and discard patterns of the mine owners, and several collections of building material and machinery were noted in passing. One machine displaying a bank of three pistons, with the word FLECK cast into the metal, is embedded in the forest floor near the old office (Building N). The Fleck Brothers Company of Philadelphia manufactured steel industrial machines and supplies in the early years of the twentieth century (Williams Company 1911). Elsewhere a metal object – perhaps a cowling for a Pelton wheel – was observed with the manufacturer’s name cast into it: B.D. STURDEVANT, BOSTON. Internet and other sources (Williams Company 1911) indicate the company was in business at least between 1884 and 1915.

The 2008 reconnaissance did not inspect the intertidal zone for features. Areas identified offshore as fill on the 1970 map (Figure 72), no doubt consisting of mine tailings, now appear to be part of the natural beach. Sam Pekovich and his brother Andrew maintain private floats offshore to moor watercraft and aircraft, roughly corresponding to the old dock location, but historic piling patterns in the intertidal zone were not noted.

Inland Mining Features

The 2008 field investigation included brief inspection with Sam Pekovich of mining equipment inland from the mining camp. The tramway was followed upslope, past the mill, to the place where the steel rails meet an overhead tram system (Figure 98). The overhead tram station consists of a tripod of steel pipe supporting a steel cable – still taut – along with the winching equipment. Built to serve workings far up the slope of Robert Barron Peak, the system has long been inoperable.

While the overhead tram appears to have been powered by a gasoline or diesel engine, evidence of two other power systems was observed inland near the lower workings. One is a steam engine (Figure 99). The other is a large Pelton wheel, fed by 700’ of 3’ diameter pipe narrowing to a 1” nozzle (Figure 100). According to Sam Pekovich, “it took three mules and five Serbs to roll the flywheel up here from the beach.”

The lower workings consist of numerous mining features centered around two adits (Figure 101). Each adit entrance contains steel rail from the tram system, and one has an ore cart blocking the way. Both are obviously too dangerous to enter and are signed to that effect. Waste rock from the adits forms an artificial bench upon which the remains of buildings can be discerned, but in 2008 they consisted of little more than rotten plank piles over metal equipment and debris. That equipment includes an electric locomotive (Figure 101), a mucker, and drills and bits. Off the waste rock at a slightly lower elevation are other building ruins, one of which contains an air compressor. Vehicles noted in the vicinity included a tractor and a two-ton Chevrolet dump truck with dual wheels.

Summary

The Admiralty Alaska Gold Mine at Funter Bay is still owned by the Pekovich family and their fellow stockholders, as it was before and during the Aleut experience there. One building has been maintained and expanded upon as the residence of Sam Pekovich, and several utility buildings have been erected in recent decades. Wartime buildings still in good enough shape to use consist of the two-story bunkhouse and an adjacent shop. Otherwise the mine’s original cabins and other buildings are quickly leaving the architectural realm to become part of the archaeological record. The mill collapsed some months after the 2008 field investigation.

Most of the wartime buildings could be identified, even though deteriorated. Referring back to the 1942 map (Figure 59), Buildings A, B, C, and D were distinguishable. Building E is completely gone, and Building F burned in 1942. Building G – built soon after the villagers arrived – is in poor condition. Building H/I is gone and in its place is a stack of wood and metal material. Nearby Building J is unusable but still has standing walls. Building K is gone but Building L (the two-story bunkhouse) and M (the adjacent shop) are standing and in use. Building N is almost whole but is not usable. Buildings O and P (two outhouses) and Building V were very small and built at the upper tide line, and no traces of them were seen in 2008. Building Q (the mill) is now collapsed. Building T exists, and – with an addition – serves as a residence. Buildings R and S are gone, and that location now holds a prefabricated utility building. The mine’s lower workings hold no buildings but most of the original machinery has been left to deteriorate in place.

The mine workings are not directly relevant to St. George villagers’ wartime experience, which centered instead on the mining camp along the shoreline. Eleven of the camp’s main wartime buildings can be detected in their original location, even if some are becoming archaeological features. Despite the camp’s general deterioration, the majority of the building remains and features of the Admiralty Alaska Gold Mine are discernible and still convey much of the site’s wartime layout and feeling.

Last updated: February 28, 2025