Last updated: January 8, 2025

Article

Bunker Hill Memory

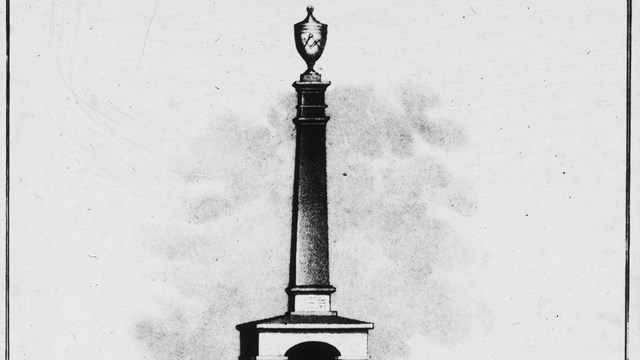

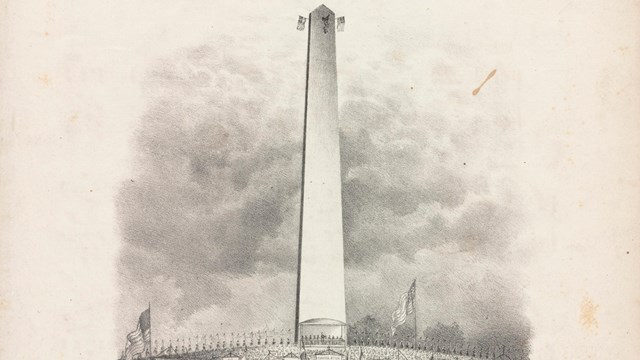

On June 17, 1775, New England soldiers faced British armed forces for the first time in a pitched battle at the Battle of Bunker Hill. During the American Revolutionary War and beyond, Bunker Hill remained a powerful symbol for the cause of American liberty. In 1823, The Bunker Hill Monument Association (BHMA) formed to create a lasting testament to the Battle.

Since the completion of the Monument in 1843, the obelisk has watched over Charlestown. It stands as an icon of Boston’s landscape and a powerful reminder of its Revolutionary history.

Throughout its existence, the Monument has meant something different to every person who has visited it. Though initially championed by members of the BHMA as a patriotic symbol of the American Revolution, their intentions do not solely define what the monument means. Horatio Greenough, an artist who helped design the monument, reflected on what it meant to him. He wrote:

“The obelisk has to my eye a singular aptitude in its form and character to call attention to a spot memorable in history. It says but one word, but it speaks loud. If I understand its voice, it says, Here! It says no more.”1

If we unpack Greenough’s words, the Bunker Hill Monument serves as an invitation rather than a statement. It marks the location of the Battle of Bunker Hill, but it does not tell its visitors how to remember or commemorate it.

This online feature invites you to explore the different meanings people have placed on the monument by reading a variety of quotes from four different time periods. As you reflect upon these voices, consider:

- What messages from the past do you see embodied in the Monument?

- What does the Monument mean to you today?

- How can we learn from the legacies of the Monument to help us shape our shared future?

1775-1825

1825-1843

1843-1893

1893-Today

Historical Memory

Historical Memory is an established area of study within the history field, and the concept refers to the ways that people understand and interpret their shared past. Historic memory is a living, changing concept, shaped by many different groups of people. Historian Michael D. Hattem says of the concept that:

Historical memories are built on specific interpretations of the past — either created or adopted — primarily for the purposes of forging group identity. A shared past, embedded with their ideals, principles, and sense of unity, allows a group to reproduce its identity.2

Monuments play a significant role of the formation of this memory, and also serve as a tool to study that memory. "Far from only being cold piles of stone, monuments have the potential to teach us how the process of commemoration has created a history of its own."3 This way of thinking about the past frames this online feature, encouraging you to think about how people have understood the Bunker Hill Monument and have found their own meanings and uses of it.4

Footnotes

- Horatio Greenough, quoted in Sarah J. Purcell, “Commemoration, Public Art, and the Changing Meaning of the Bunker Hill Monument,” The Public Historian, Spring 2003, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.1525/tph.2003.25.2.55.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Aa900678f03cd372f2b0f357d32c3cd11&ab_segments=0%2FSYC-6451%2Ftest&origin=&acceptTC=1, 64.

- Michael D. Hattem, Past and Prologue: Politics and Memory in the American Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 5.

- Sarah J. Purcell, "Commemoration, public art, and the changing meaning of the Bunker Hill Monument," The Public Historian 25, no. 2 (2003), 57

- For further reading on the concept of Historical Memory, see Alfred F. Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999); Hattem, Past and Prologue; Purcell, "Commemoration"; David Glassberg, “Public History and the Study of Memory,” The Public Historian 18, no. 2 (1996);