|

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

A frenzied boomtown during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897-98, today Dyea is all but a ghost town. Step off the beaten path and get to know modern and historic Dyea. A visit to Dyea provides a great opportunity to experience the nature and wildlife of Southeast Alaska, but this scenic area in the Taiya River Valley is a far cry from what Dyea was like at the turn of the 20th century. Dyea became a boomtown during the Klondike Gold Rush because it was the start of the famous Chilkoot National Historic Trail. Thousands of people poured through Dyea on their way to the gold fields. An Important Trade RouteExactly when Dyea was established is uncertain. Oral history accounts indicate that at one time it was a small permanent village. However, in the decades before the gold rush Dyea was a seasonal fishing camp and staging area for trade trips between the coast and the interior. In fact, the name Dayéi means “to pack.” The Chilkoot pass is one of only three passes that can be used all winter in the northern Lynn Canal area.The Chilkat Tlingit people from Klukwan used this corridor to trade with the interior First Nations people. It was their main trade route to the interior and they did not permit others to use the pass. They provided goods from the interior to Russian, Boston, and Hudson's Bay trading companies. Their control reached beyond Dyea, even burning Fort Selkirk in the Yukon in 1852 when the Hudson's Bay Company attempted to trade directly with the interior First Nations people. In 1879, U.S. Navy Commander L.A. Beardsley reached an agreement with the Chilkat Tlingits whereby miners would be permitted to reach the Yukon via the passes but would not interfere with their regular trade. Tlingit guides accompanied the first party over in May 1880, and transported the miners' gear for a fee. This trip set the foundation for the Tlingit packing business, which thrived during the gold rush.

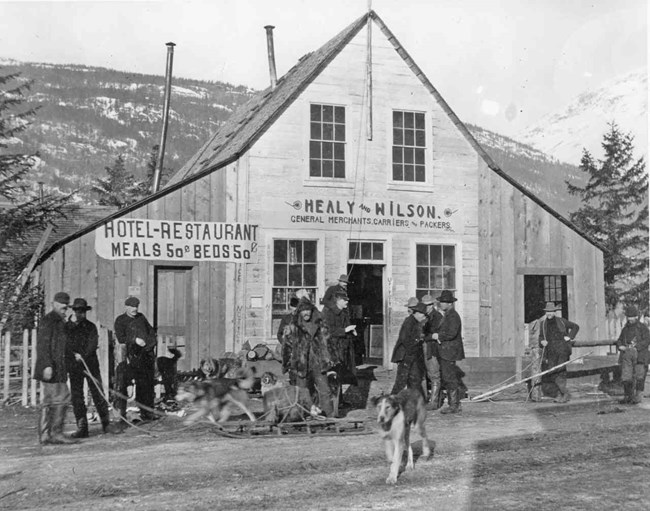

National Archives, BR-1-A-10C Healy & Wilson Trading PostDyea's status changed with the establishment of the Healy & Wilson trading post in the mid‑1880s. Before coming to Alaska, John J. Healy had been a hunter, trapper, soldier, prospector, whiskey trader, editor, guide, Indian scout, and sheriff. He was living in Montana Territory when he heard about the early, pre-Klondike Yukon gold strikes; dropping everything, he headed north. Edgar Wilson was Healy’s partner and brother-in-law. Not much is known of him. Wilson may have arrived in Dyea a season or two before Healey’s appearance, laying the groundwork for the trading post. An early map shows the Healy & Wilson trading post consisting of a wood‑frame trading post, which was a combination store and residence, a barn and nearby garden. The Tlingit Village was located just upriver. The post was an important supply and information point for prospectors heading into the Yukon basin before the Klondike Gold Rush. Alaska Natives and First Nation peoples gathered there, particularly in the spring, to help prospectors pack their outfits over the Chilkoot Pass.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George & Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55749b. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

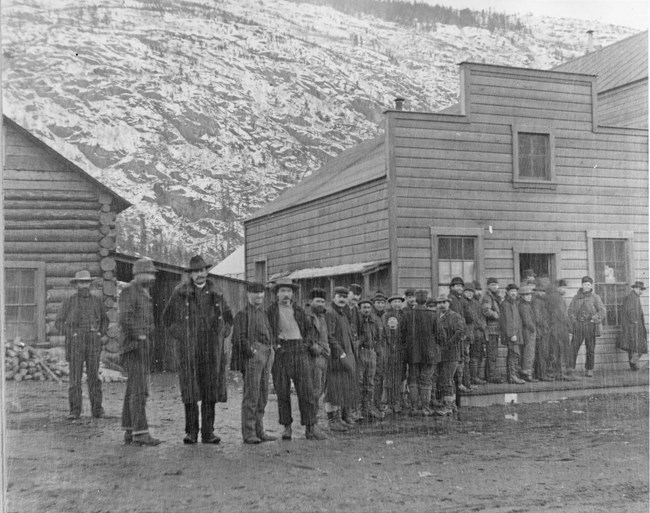

National Archives, BR-1-A-10B Boomtown DyeaDyea's real boom began in the fall of 1897. When word of the wealth of the Klondike strike splashed onto the world's newspapers in mid‑July 1897, traffic up the Inside Passage grew to a frenzied pace. For months, jammed boatloads of prospectors disembarked in Dyea and streamed north over the Chilkoot Pass. Few people remained in the area very long. As late as September 1897, Dyea was still nothing more than the Healy & Wilson trading post, a few saloons, the Tlingit encampment, and a motley assemblage of tents. In October, speculators mapped out a townsite, but Dyea's biggest growth did not begin until the Yukon River system started to freeze up and the winter storms slowed traffic on the Chilkoot Trail. Without the ability to dash up the trails, people began spending more time in Dyea and it became more town-like.

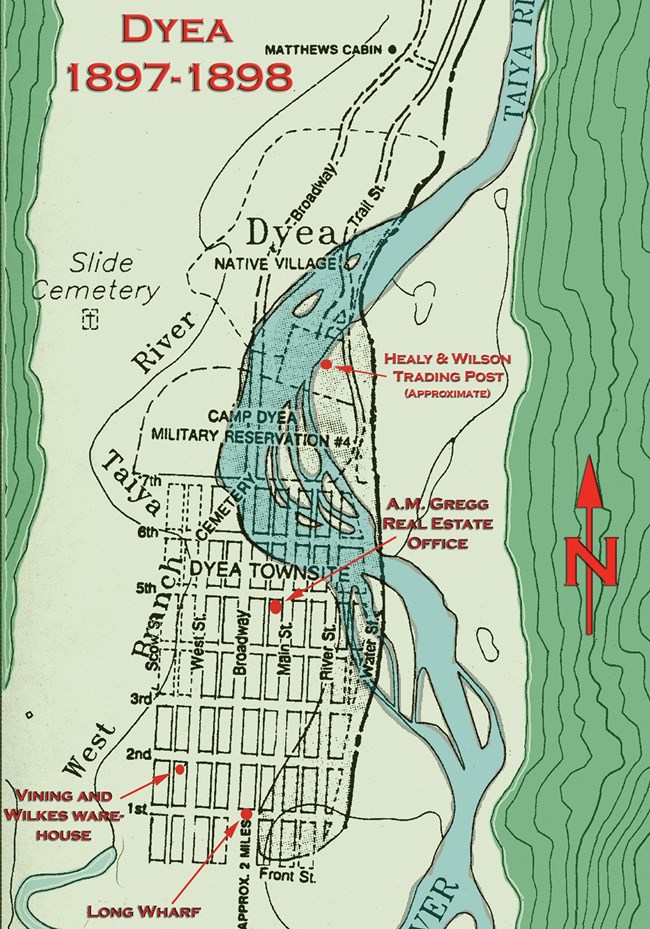

During the winter of 1897-1898, Dyea was large in size and multifaceted in function. The downtown area was about five blocks wide and eight blocks long. At the height of its prosperity, the town boasted over 150 businesses, with the large majority of them being restaurants, hotels, supply houses, and saloons. Manufacturing was limited to two breweries. Attorneys, bankers, freighting companies, photographers, steamship and real estate agents were also plentiful. To care for your health, there were drug stores, doctors, a dentist, two hospitals, and three undertakers. Although the town doesn’t appear to have had any type of formal government, a Chamber of Commerce developed as did a volunteer fire department (but without a building) and a school that ran from May 1898 – June 1900. To connect with the outside world, the town had two newspapers (the Dyea Trail and the Dyea Press) and two telephone companies, one that ran its line up the Chilkoot Trail to Bennett and the other that ran its line to Skagway. There were also two wharfs, many warehouses and freight sorting areas, and a sawmill. The town also had one church, of the Methodist-Episcopalian denomination. Camp Dyea Immediately north of downtown was Camp Dyea. U.S. Army troops first arrived here about March 1, 1898, and soon their tents were scattered across a large field south of the Healy & Wilson trading post. When the troops arrived in Dyea, they paid little attention to the site where they established their camp. But drainage problems existed at the site, the nearest potable water was over a half‑mile away, and the camp was not directly accessible by water. Therefore, the troops sought out another location. In October 1898 they moved three miles south along the west side of Taiya Inlet. There the army secured the Dyea‑Klondike Transportation Company dock and buildings to use. North of Town North of the downtown area River Street wound along the banks of the Taiya River up to the Healy & Wilson store, the mid-part of town. Beyond that, the traveler on River Street encountered the Tlingit Village, and other boomtown stores scattered along the road. Near the northern end of town, approximately two miles from the high tide line another business center catered to southbound traffic. Dyea officially ended at the Kinney Bridge. Dyea's DownfallDyea competed on fairly even terms with Skagway through the winter of 1897‑1898, but in the spring, Dyea began to lose its competitive edge. On April 3, 1898, there was a massive snow slide, known as the "Palm Sunday Avalanche," on the Chilkoot Trail. This disaster happened north of Sheep Camp and killed over 70 people. This brought worldwide negative publicity and some travelers steered away from Dyea. The opening of the Yukon River brought a mass exodus from the town as the stampeders left for Dawson.

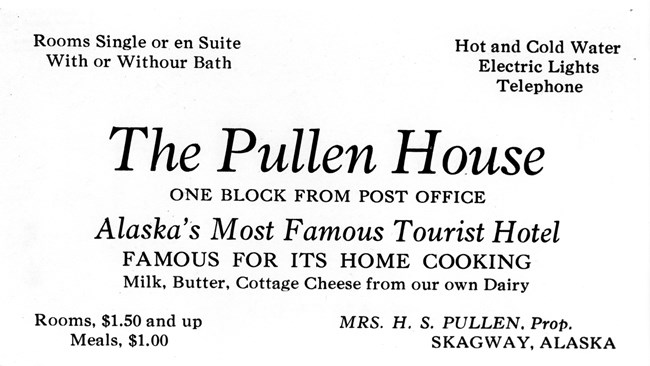

After the Gold RushOnce people left town, the valley began to show opportunities as a farming area. Four operators there raised vegetables for the Skagway market in 1900, and a few continued intermittently for another forty years. Joseph Waughn, William Matthews, Ernest Richter, Mary Hart, Emil Klatt and William Maksym all claimed land in Dyea before 1915. All relinquished their land to or were bought out by Harriet Pullen, the well‑known Skagway hotel owner.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George & Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 59771a. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. It appears that the only buildings for which any substantial evidence is left were re‑used by farmers or other homesteaders after the gold rush. Many ruins still remain at the old townsite but identification of the ruins is difficult and many questions still remain. The town is now a major archeological site. In February 1978, the National Park Service bought much of the old townsite of Dyea.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 59777g. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. |

Last updated: July 9, 2025