You’re hiking eight hundred and fifty feet above the hot canyon floor, moving carefully through a narrow slot canyon and enjoying an occasional breath of cool air, when suddenly, something wondrous comes into view. A ribbon of rock arched proudly against the blue desert sky. Freestanding rock, that compels you to stop and wonder. How did it come to be? Why doesn’t it fall? What does this arch tell me about the incredible geology of Zion National Park? For centuries people have been drawn to these unusual geologic formations. Depending on their cultural background, people throughout human history and prehistory may have felt fear or spiritual awe at the sight of such a large hole in rock, put there by some mysterious force, or perhaps an unfriendly deity. It is equally certain that individuals from other cultural backgrounds saw only grace and beauty in these natural spans. Still, it is a rare human being who can gaze upon a natural arch, or bridge of stone, and not be touched by being in the presence of something special. Rock shouldn’t take flight in the sky, but when it does, in scorn of physical laws, people take notice. A natural arch is formed when deep cracks penetrate into a sandstone layer. Erosion wears away the exposed rock layers and the surface cracks expand, isolating narrow sandstone walls, or fins. Water, frost, and the release of tensions in the rock cause crumbling and flaking of the porous sandstone and eventually cut through some of the fins. The resulting holes become enlarged to arch proportions by rockfalls and weathering. Architecturally, arches are the most stable load bearing structure, but through weathering, eventually all arches collapse, leaving only buttresses that will inevitably give way to the unyielding forces of erosion.

Photo by Chad Utterback Among the many arches in Zion, two stand out: Crawford Arch and Kolob Arch. Crawford Arch is the most visible, clinging to the base of Bridge Mountain a thousand feet above the canyon floor, and pointed out to casual observers by an interpretive sign located on the front patio of the Human History Museum. For years, rangers in Zion told visitors that this span was a natural bridge (thus the mountain’s name). The Natural Arch and Bridge Society identifies a bridge as a subtype of arch that is primarily water-formed, so by geologic standards it is an arch and in the last years of the twentieth century was referred to as “The arch on Bridge Mountain.” To avoid confusion, the National Park Service eventually named the span Crawford Arch in honor of the Crawford family--among the first Mormon settlers called to the canyon, who toiled and farmed beneath its watchful gaze. Although undoubtedly seen by Zion’s Native Peoples for centuries, the names they gave to this arch in the sky have been lost in the mists of time.

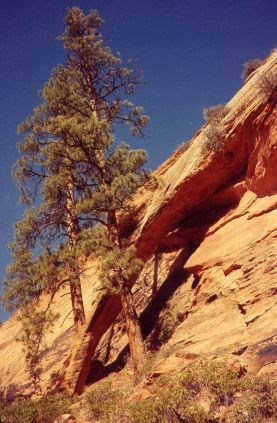

The other famous arch in Zion is not so easily seen. Located deep in the backcountry of Zion National Park’s Kolob Canyons District, and hidden in a small side canyon, sits Kolob Arch, perched high on the canyon wall with a majestic curve like a giant condor’s wing. Because of its remote location and virtual inaccessibility, Kolob Arch for years has challenged cowboys, rangers, hikers, climbers, and photographers alike. For most of the twentieth century many believed that Kolob was in fact the world’s largest freestanding arch, leading to years of debate and the motivation for various parties of adventurous thrill seekers to climb on and around the massive span in hopes of securing a defensible measurement. Despite its isolated location, Kolob Arch has become a favorite backcountry destination for thousands of visitors to Zion. They discover what most arch seekers will tell you: while beauty awaits every seeker at the end of the path, the reward begins unfolding at the trailhead. Along the trail to Kolob Arch lies some of the most beautiful scenery in Zion. Geology becomes art as the La Verkin Creek, with its soothing sounds of life-giving water, sculpts some of the most colorful canyon walls in Southwestern Utah. Awe inspiring views of the Kolob Terrace along the trail give a tired hiker many places to stop and recharge while gazing upon the high plateau country of Zion. Wildlife abounds in these protected canyons and hikers will encounter reptiles, birds, and mammals. Seven miles along the trail, one is rewarded with a sight not seen by most of Zion’s four million annual visitors, the impressive expanse of Kolob Arch. Most experts now agree that Kolob Arch is not the world’s largest span in terms of measurement by width and size, but visitors concur with the claim that it is certainly one of the most beautiful and massive arches in creation surrounded and protected by the majestic scenery of Zion. Zion National Park holds countless splendors of geology, plants, and animals, but it is the wondrous arch that never fails to mystify. We draw in a sharp breath, our mouth opens in awe, and our heart leaps up as we gaze at these impossible, wondrous spans of rock taking flight. |

Last updated: August 2, 2022