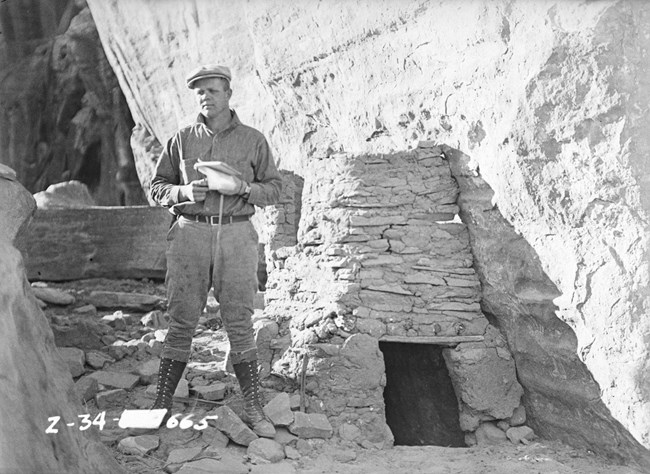

People have lived in and around Zion Canyon for thousands of years. It has been home to a number of native peoples including but not limited to the Archaic, Ancestral Puebloan, and Southern Paiute. These indigenous people built homes, raised families, and established communities on land that is now part of Zion National Park. Early Archeology

Archeology TodayToday, archeology in the National Park Service is very different than in Wetherill’s time. Sites are only excavated if there is a risk of damage from natural or human causes such as erosion, flooding, vandalism, or construction. Archeologists instead prefer to leave sites and artifacts undisturbed in order to preserve the context in which the objects were discovered and care for them through surveying, recording, monitoring, and stabilization. Tribal consultation is also an important part of this process. Consultation between associated tribes and park staff helps develop best management practices for the protection of archeological sites and significant cultural resources for future generations. Archeologists at Zion currently care for over five hundred sites within the park and regularly record new ones.

National Historic Preservation ActUnder section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, before the National Park Service changes anything about the park, we have to study how change might affect plants, animals, and history. In order to do that, archeologists survey the project area to see if work might affect buried artifacts. This assists both archeologists and project managers in minimizing or eliminating potential effects. If discoveries are made during the project, park archeologists secure and investigate the area in order to prevent damage. Any new discoveries are reported to state and federal agencies. Site StewardshipPark archeologists depend on the general public to act as site stewards and help protect cultural resources. Because looting and vandalism present such significant threats to archeological sites and artifacts, the National Park Service relies on volunteers to help document and monitor these important resources. Learn more about how to best preserve and protect the past.

Archeological Sites

Learn more about protecting archeological sites at Zion.

Artifacts

Unearth examples of what people in the past made, purchased, and collected.

Early European Americans in Zion

Find out more about the people who came to the canyon in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Museum Collections & Archives

Explore museum and archives collections of Zion. |

Last updated: January 4, 2026