NPS / Frank J Haynes The road construction that began in Yellowstone in the 1870s became the United States’ first large-scale road plan and served as a model for other parks, especially in its use of local materials. Even after Yellowstone could be reached by train in 1883, the difficulty of transport and road construction in a geologically and climatically challenging terrain required enormous labor and innovative engineering. The development of a road system was essential in making Yellowstone more accessible to the public. Over the years, advances in road standards and construction technology have led to changes in the roads’ appearance, but the overall design has remained largely intact, along with many historical features such as bridges, culverts, and guardrails. Hiram Chittenden The 300-mile, figure-eight road system that connects Yellowstone’s five entrances, developed areas, and major attractions remains largely the same as when engineer Major Hiram Chittenden finished his work on it in 1905. Through his role in designing Yellowstone’s roads, bridges, and other structures, Chittenden had a lasting effect on the appearance of our national parks. While stating that they should be maintained “as nearly as possible in their natural condition, unchanged by the hand of man,” he would use masonry and add or remove trees and other landscaping so that “the roads will themselves be made one of the interesting features of this interesting region.” Throughout the park, he replaced many wooden bridges with steel or concrete. His most difficult project was the replacement of the rickety trestle at Golden Gate with a 200-foot viaduct, a series of 11 concrete arches built into the cliff wall over a canyon. In 1902 he persuaded Congress to make the appropriation needed to complete the park’s road system. This included some of Chittenden’s signature achievements: the road over Sylvan Pass, the road to Mount Washburn (now called Chittenden Road), and the bridge over the Yellowstone River above the Upper Falls, which at last provided a means of getting to the east bank of the river without going all the way north to Baronett’s bridge. Over the years, the Golden Gate viaduct had to be reconstructed, and the bridge over the Yellowstone River was condemned in 1959. A campaign to preserve the original bridge by building the new Chittenden Memorial Bridge in a different place was thwarted by the discovery that Chittenden had used the only logical location. Before leaving Yellowstone in 1906, Chittenden was also responsible for overseeing the redesign of the park’s north entrance, including construction of the arch and, through irrigation, fertilization, and the planting of alfalfa, transforming 50 acres adjacent to Gardiner into a green field that would provide winter forage for pronghorn and other game animals. Today, efforts are being made to restore the field to its natural condition, but the Roosevelt Arch endures.

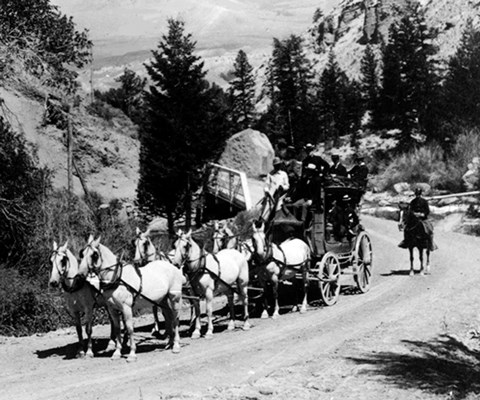

NPS Touring the Park At first, travel to and within the park was difficult. Visitors had to transport themselves or patronize a costly transportation enterprise. In the park, they found only a few places for food and lodging. Access improved in 1883 when the Northern Pacific Railroad reached Cinnabar, Montana, a town near the north entrance. A typical tour began when visitors descended from the train in Cinnabar, boarded large “tally ho” stagecoaches, and headed up the scenic Gardner Canyon to Mammoth Hot Springs. After checking into the hotel, they toured the hot springs. For the next four days, they bounced along in passenger coaches called “Yellowstone wagons,” which had to be unloaded at steep grades. Each night visitors enjoyed a warm bed and a lavish meal at a grand hotel. These visitors carried home unforgettable memories of experiences and sights, and they wrote hundreds of accounts of their trips. They recommended the tour to their friends, and each year more came to Yellowstone to see its wonders. When the first automobile entered in 1915, Yellowstone truly became a national park, accessible to anyone who could afford a car. More Information

|

Last updated: April 18, 2025