Retta: On a sweltering August day - August 26th, 1920 to be exact - Carrie Chapman Catt was in her office in New York when the phone rang.

“The Secretary has signed the proclamation.”

This is how she learned the news. As “quietly as that,” suffragist Maud Wood Park would later write. She was with Catt to witness what many considered the final step in the women’s suffrage fight that had lasted over seventy years. And it was a phone call. Park wrote, “We were all too stunned to make any comment.”

[music]

Of course, the Secretary of State was merely confirming what the suffragists already knew. The State of Tennessee had ratified the 19th amendment - or the Anthony amendment - as many were calling it by that time. And with that, they had enough states to make sure that the Anthony Amendment was adopted into the U.S. Constitution. The country would never be the same again.

The 19th Amendment officially eliminated sex as a barrier to voting. And it expanded voting rights to more people than any other single change in American history.

But, in the end, the Susan B. Anthony Amendment didn’t completely reflect Susan B. Anthony’s convictions about a citizen’s right to vote. Because again, it just says what states can’t do. It protects women from sex discrimination in voting...it doesn’t make sure that all citizens can vote.

So if you feel like the women’s suffrage story ending in a phone call is not the ending you were hoping for, might we suggest that the story is, in fact, not over.

This is And Nothing Less. It’s Episode 7: Failure is Impossible.

R: I’m Retta. RD: And I’m Rosario Dawson.

[THEME]

RD: So now what?

Imagine spending your whole life fighting for something. And then you get it. What now?

If you’re a suffragist in August of 1920, it’s hard to imagine what celebration looks and feels like. Because you’ve just won a battle.

R: And battles are bloody!

RD: But...winning the battle doesn’t mean you’ve won the war.

RD: Let’s remember one of our big myths from Episode 2 - That this fight was only about the vote. You also had rights for the poor, immigration rights, labor laws, marital rights. It goes on and on.

With sex eliminated as a barrier to voting, let’s see...Title 7 of the Civil Rights Act was a huge achievement to protect women from workplace discrimination. But we’d have to wait until 1964 for that. And the first woman was finally appointed to the United States Supreme Court, but not until 1981.

Battles in a war that has lasted for generations.

RD: But, let’s go back to that Fall of 1920. It was a presidential election year with a whole new set of Americans legally able to vote.

R: That sounds like a lot of change.

RD: Yes, but, you have to remember that, by this point, fifteen states had already granted women full suffrage. So women weren’t exactly entering the polls in one fell swoop. That said, big promises were made all around. Suffragists promised voters that women would clean up dirty politics with progressive reforms. And Anti-suffragists promised voters that dirty politics would compromise women’s morality.

Kristi Andersen: Many suffragists argued for women's right to vote on the basis that women would do good things, would have a good impact on that nation, particularly by sort of cleaning up things.

RD: Kristi Andersen is a political scientist and the author of After Suffrage.

Andersen: The notion was very common that women were quite different than men. They had different interests. They would act according to the public good. They would, you know, help children and protect the vulnerable. So I think there was the anticipation that that would happen and kind of excitement about it.

RD: In the end, Republican Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio defeated Democratic Governor James Cox, also of Ohio, in that 1920 November election.

Democratic President Woodrow Wilson had privately hoped for a third term, which was still a thing back then, but party leaders were unwilling to re-nominate the ailing and unpopular incumbent.

Andersen: The 1920 election itself was it was pretty much a foregone conclusion.

People were really tired of the war. They were not very positive about Wilson at that point. The wartime president, they wanted to get back to normalcy. And that's kind of what the rebuild. There was a postwar recession. And what the Republicans campaigned on essentially was, you know, it's a return to normalcy. You know, thank God the bad stuff is over. Let's get back to normal.

I still think women were generally excited to vote in the in that election.

R: So how many women voted?

RD: Well Andersen says that’s hard to answer.

Andersen: One part of the answer is we don't know really because unlike today where we know down to very small details who voted no because exit polls and surveys, there were no surveys. Voting places didn't keep count of how many men or how many women voted. Certainly the number of people voting went up between 1916 and 1920, I think from something like 18 and a half million to twenty six, almost twenty seven million people.

If you looked at the just the 1920 election, it wasn't magically, you know, a button was not pushed through as a lever was not pulled that allowed all women to vote.

And there were four or five southern states. I think Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama or South Carolina, which really didn't allow them to vote at all. They had, you know, the amendment wasn't ratified until August, and some states had prior registration deadlines. So you already had to be registered and they didn't. They refused to change those for women. So basically, women couldn't vote in the presidential election in those states and in many other localities, the election officials made it difficult or refused to make it easier for women to vote, to register to, you know, could get to the polls and so forth. So it would been hard to imagine that there would be a huge turnout among women in that particular election.

R: Full suffrage did expand opportunities for women to run for office. Though this wasn’t necessarily something suffragists included in their platform.

Andersen: The suffragists mostly did not talk about women being able to run for office as a possible result of suffrage. I mean that that I think they felt strategically wouldn't go over well. You know that. OK. Give the women right to vote, but we don't want them running things. And so that was not really talked about.

R: You did see women in elected office before the 19th Amendment, but after, the numbers jumped.

[music]

Between 1920 and 1923, at least 22 women became elected mayors of small towns in places like Red Cloud, Nebraska and Duluth, Georgia.

Bertha Landes became the first big city mayor of Seattle in 1926.

In Yoncalla, Oregon, the entire city council was replaced by women backed by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.

Even some anti-suffs ended up entering politics after ratification. Some women voted and some ran for office. Elizabeth Lowell Putnam was both the vice president of the Republican Club of Massachusetts and first woman elected president of the Massachusetts Electoral College.

Throughout the 1920s, states like New Mexico, New York, Kentucky and Indiana saw women elected to their offices of Secretary of State and treasurer.

Andersen: I found it really interesting to look at press coverage in the 20s as this started to happen, as women were elected more frequently to state legislatures and then to Congress and then to the Senate how they were described, what the fears were, what their perceptions were of how they were treated.

I think that much of the press coverage was in a way trying to reassure readers that the women, even though they had run for office, even though they were there was one about I think it was Florence Knapp, who was the secretary of state for New York, all elected. There was a newspaper article about her first appearance in front of the state assembly in New York. And they said something like “she was a vision in lavender dress. And her voice was carefully modulated and feminine,” you know, but she was standing up in front of the, you know, the probably male or maybe all male state assembly. So here she is in this position. But don't worry, she's still womanly and still wearing a nice dress and still, you know, speaking softly.

R: Whether or not it was feminine, women on every side of the aisle were also flexing their political muscle when it came to policy. Andersen: There were a lot of hopes for reforms, you know, regarding child labor and minimum wage in slums, improvement in education. And but one of the issues, one of the big kind of stumbling blocks was the debate among women, among activist women as to whether they should pursue these goals that lots of women shared, these kind of progressive goals, as a bloc of women coming to the electorate or through the parties, which is how things have always happened.

R: This debate was on display at one of the last meetings of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. This group rebrands itself as the League of Women Voters.

Andersen: Here were people like Carrie Chapman Catt who said politics takes place and policy is made by the political parties. And if we're going to have any power and we're going to get things done that we want to get done, we have to work through the political parties, not only. But certainly we have to work through the parties. Other people, Maude Wood Park, for example, who is the first president of the League of Women Voters, really thought that the league could take the lead in pulling together women, Republicans or Democrats. Because, you know, they all agreed more or less on some of these policy changes that they thought should be made and they should not necessarily stand outside the parties, but be that women should should put their energies into this women's movement essentially, rather than work through the parties.

[music]

R: One example of this “bloc strategy” was the formation of the Women’s Joint Congressional Committee or the WJCC.

Twenty organizations banded together including the League of Women Voters, the National Women’s Trade Union League and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.

And their first legislative win in 1921 was called the Sheppard Towner Maternity and Infancy Act. It provided funds to states for maternal and child health clinics to address the appallingly high mortality rates at the time.

RD: For the most part though, the power of a woman’s voting bloc did not appear overnight, as some had predicted. If it ever appeared at all.

[music]

In the early 1920s, women helped to only slightly increase overall voter turnout. And, according to historians, they rarely flipped elections in these early days.

The League of Women Voters needed to start a “Get Out the Vote” campaign as early as 1924. A mission that would continue for years to come.

R: At this point we have to ask ourselves about the women who didn’t vote. And why?

That’s coming up on And Nothing Less.

// Break //

R: We’ve made it to the 1920s. Victory! Let’s read some of the headlines.

“Is Women’s Suffrage a Failure?” Oh dear. Ok well that wasn’t a great one.

RD: where’s that from?

R: Good Housekeeping in 1924.

RD: Ok well this is from Harper’s in 1925: “Are Women a Failure in Politics?”

R: Oh my god c’mon guys!

RD: You and I know headlines exaggerate. But we’ve established that women weren’t exactly turning out in droves to vote after the 19th Amendment was ratified. Kristi Anderson said it’s hard to know exactly what was happening state by state because voting records were kept so differently.

In their book “Counting Women’s Ballots”, J. Kevin Corder and Christina Wolbrecht use a sample size of ten states from 1920 to estimate that just 36 percent of eligible women turned out to vote in 1920 compared with 68 percent of eligible men.

But now our question is - why.

R: Right. Is this a question of gender or sex at all? Is a better question - could all women vote even if they wanted to?

[Music]

RD: Let’s see if we can answer that.

By now we know that states control voting. Even after the Anthony Amendment is ratified, states have the ability to set voting restrictions. In some cases, really extreme restrictions.

Remember that after the 19th Amendment was certified in August 1920, some states' voter registration deadlines had passed, and they refused to re-open registration for newly enfranchised women.

Also, by the end of the 1920s, all of the southern states, plus 12 more outside of the south, required literacy or educational tests before you could vote. Not to mention poll taxes. These intentional roadblocks were a blow to black voters, as well as new English speakers, poor Americans and Native Americans. It was also hard on women.

R: Then there was the factor of citizenship, which marriage often complicated, and immigration always complicated.

RD: You mentioned marriage Retta...you’re gonna love this fun fact. In the early 1900s, if you were married to a man who wasn’t an American citizen, you lost your citizenship and your right to vote. I mean, the fun never stopped.

R: And for Native Americans, citizenship was even more complicated. Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, but many Native people would reject something they never asked for. In other words, they didn’t want to be forced to become citizens of the U.S. if it meant they had to abandon and disown their culture or land.

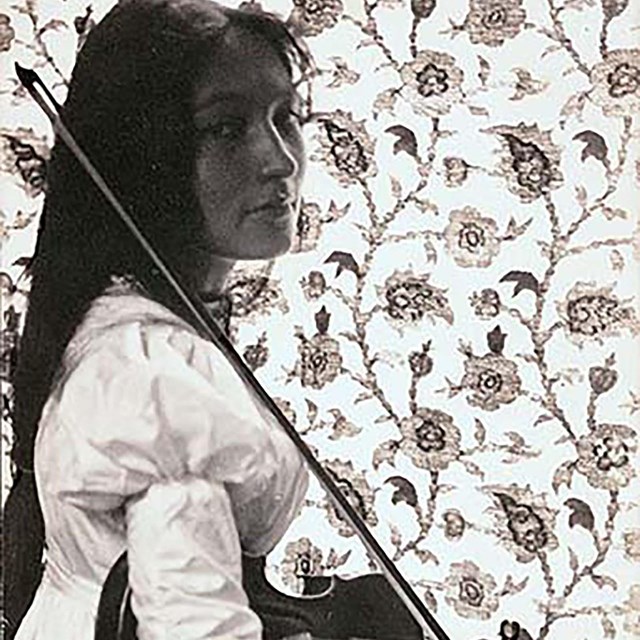

RD: And for women like Zitkala-Sa of the Lakota, who did want to vote in US elections, there were often additional barriers to the polls. While the Citizenship Act of 1924 granted, you guessed it, citizenship to Native Americans, it didn’t guarantee indigenous people the right to vote.

R: That decision stayed with the states. And that never violated the 19th Amendment. So Zitkala-Sa formed the National Council of American Indians in 1926, working to unite tribes across the US to fight for the right to vote for all Native Americans.

RD: She believed that Native Americans, as the original occupants of the land, needed to be represented in the current system of government. She ran voter registration drives, partnered with the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, and lobbied for legislation that she felt would benefit Native people.

R: Then you have Asian-born Americans whose citizenship and right to vote were denied through a series of laws for over a hundred years. This changed with the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943 and the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act in 1952.

RD: And perhaps no group of Americans have been more shut out of voting than African Americans.

Here’s historian Martha Jones.

Martha Jones: What we see after 1920 is that some American women win the right to vote with the 19th Amendment and many women do not. African-American women in northern and western states will win the vote in 1920. And will go to the polls. Become part of Republican Party politics with enthusiasm, with gusto, and very much become part of political machines and influence elections.

They'll run for office even, and at the same time in those southern states where black men have long now been disenfranchised, by 1920, black women will become equal to their male counterparts, equal in the sense that they, too, will be kept from the polls by poll taxes and literacy tests

RD: In 1920 some black women did manage to register to vote in the South, despite attempts to bar them. They fell through the cracks, you could say. But within a few years, that would get squashed. They were systematically subjected to the same tactics that black men had been for decades. One tactic was “white people first” registration, leaving African Americans to wait for hours. Another was forcing registrants to read passages from the constitution before being allowed to vote. Or worse, they were blocked from the polls by outright intimidation or violence.

And when some black women asked for help, from the organizations that had been dedicated to suffrage for decades, they were flatly turned away.

Lisa Tetrault: So you're gonna go to these suffrage organizations and you're gonna say, great, you know, I'm glad we got that obstacle removed, sex. But what about, you know, these three other ones I'm facing? RD: Here again is Lisa Tetrault, the author of The Myth of Seneca Falls.

Tetrault: And those are white organizations, those mainstream white organizations. Carrie Chapman Catt’s NAWSA and Alice Paul’s National Woman's Party. You're going to say, I'm sorry, but our fight is over. We can't help you. That's a race issue. That's not a gender issue. And so those organizations turn their back on the millions and millions and millions of women who are still facing restrictions at the state level. And those women will continue to organize for suffrage after 1920.

And for many of those women, they won't get a decisive victory until 1965 with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which will finally strike down those restrictions and allow them to register.

R: And for Tetrault and so many women and men who have dedicated their lives to suffrage history, it would be a mistake to think the story ends in 1920. That would be to ignore the women who were left behind that year. Who fought for equality but never got to enjoy it.

RD: Which is why our centennial commemoration has to be more than a celebration, according to our experts. It has to be a commitment to keeping the history alive. And a commitment to democracy.

First Alison Parker.

Parker: It has to be a recognition of the fact that voting rights are always something that are for hard fought for. And you can never assume that winning on a kind of superficial level is enough. You have to fight to enforce those laws and those constitutional amendments. And if you don't have a unified front, it's going to be much harder to do so for people who are racial minorities, if they don't have support from that white majority, they’re going to have a very hard time celebrating.

RD: And Martha Jones.

Jones: For me, the best thing that can come out of this anniversary year is a deepened understanding of how precious, how, fought for, how essential voting rights are and have been for a very long time in this country. I think the struggle around the 19th Amendment help us appreciate the ways in which arbitrary ideas about human difference, racism and sexism, have interfered with our arrival at some sort of more complete democracy.

RD: Elaine Weiss.

Weiss: I think it's a great opportunity for us to recognize what an extraordinary social and political movement this was and something that we're not taught very much that we have not been well versed in. That's been kind of dismissed like, “oh, yeah, I was just the women that got the vote.” This was an amazing civil rights battle, and that's what it was. It was like all rights battle.

RD: And Lisa Tetrault.

Tetrault: To me, it gives us an opportunity to talk about what it means to vote in this country, and we try to understand what the suffrage movement accomplished, and what it didn't accomplish. And in many ways, if we just take a triumphal approach to this, we think the story's over and it's just about remembering and not about calling us to action in the present when in fact, to me what the 19th Amendment didn't accomplish was securing any right to vote for any citizen. And if we tell the story about there being a right to vote that somehow people are invested with, we think that if people don't have access to the vote, they must have done something to abridge of their right. And in fact, that's not true.

And this centennial gives us an opportunity to revisit the health of our democracy and ask ourselves what have we won and what do we still need to fight for?

RD: For starters - women, their rights, and nothing less.

[riffing]

[music]

RD: I’m Rosario Dawson.

R: And I’m Retta Thanks for listening.

[CREDITS]

This was And Nothing Less, from the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission and PRX. This podcast was envisioned by W-S-C-C Executive Director Anna Laymon with support from Kelsey Millay.

The production team is Executive Producer Genevieve Sponsler, Producer & Audio Engineer Samantha Gattsek, and Writer & Producer Robin Linn. Our music is by Erica Huang.

The historical content used to create these stories was brought to you by the National Park Service -- teachers can download companion lesson plans at go.nps.gov/suffragepodcast.

For even more suffrage history, visit the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission at womensvote100.org.

[PRX AUDIO SIGNATURE]

Zitkala-Ša

Zitkala-Ša Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt Dr. Alice Paul

Dr. Alice Paul Places of Carrie Chapman Catt

Places of Carrie Chapman Catt National MonumentBelmont-Paul Women's Equality

National MonumentBelmont-Paul Women's Equality AlabamaBirmingham Civil Rights Nat'l Monument

AlabamaBirmingham Civil Rights Nat'l Monument Legacies of Woman SuffrageBeyond 1920

Legacies of Woman SuffrageBeyond 1920 What’s Next?

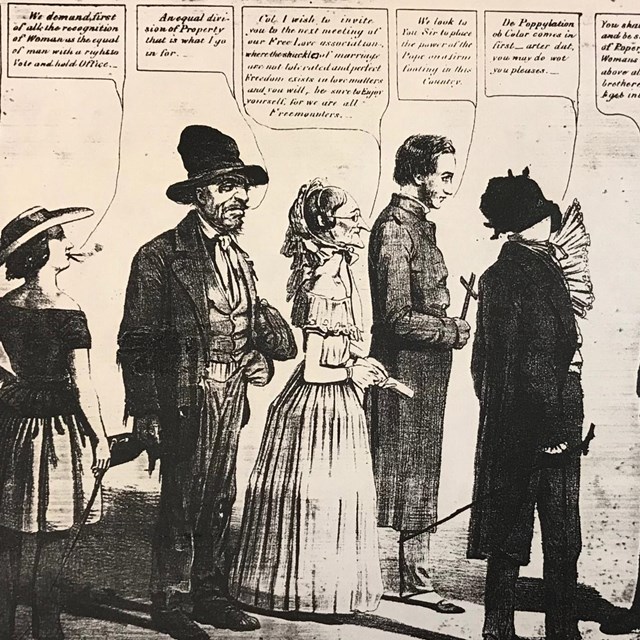

What’s Next? Anti-Suffrage in the United States

Anti-Suffrage in the United States Everything But The Vote Still To Be Won

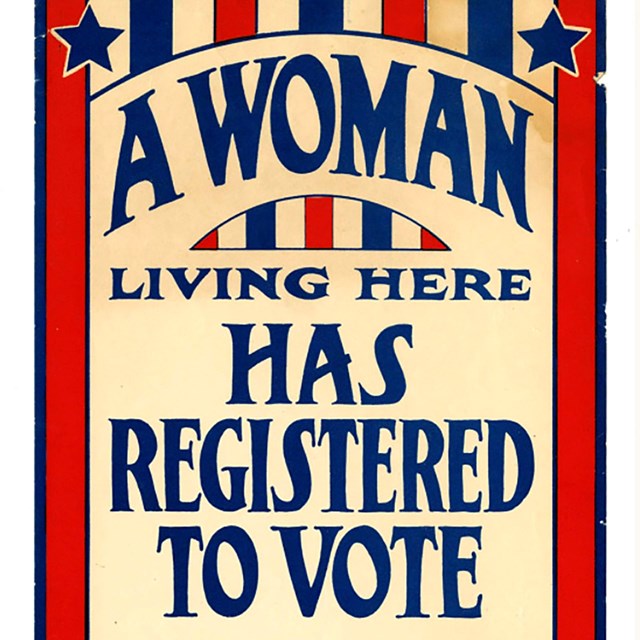

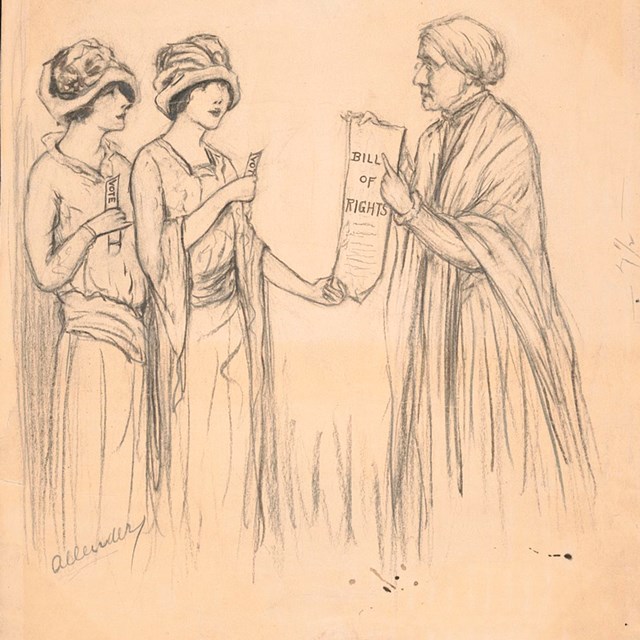

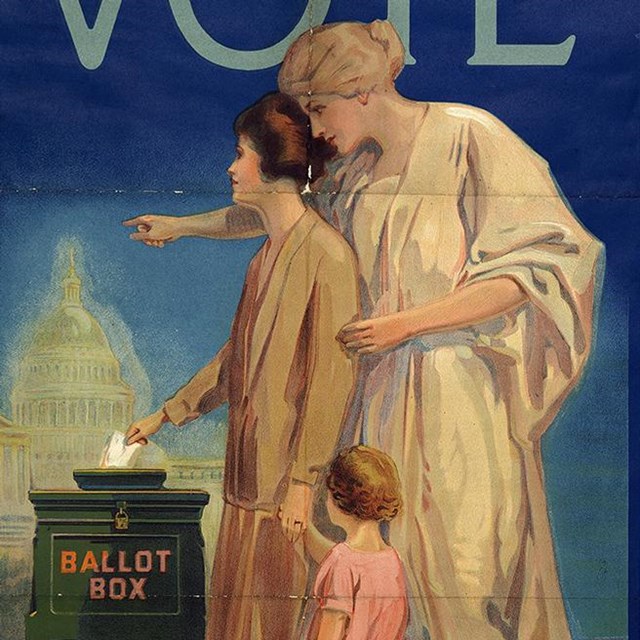

Everything But The Vote Still To Be Won League of Women Voters Poster, 1920

League of Women Voters Poster, 1920 Suffrage Proclaimed by Colby

Suffrage Proclaimed by Colby