Part of a series of articles titled Suffrage in America: The 15th and 19th Amendments.

Previous: Voting Rights: Celebrations of Success

Article

Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003654393/

A century ago, people who demanded universal suffrage were considered idealistic, strange, or even dangerous. Now we take these ideas for granted as essential to American democracy. The dreams of previous generations have become the common sense of today.

Transforming ideas to policies is a slow process full of complex challenges. Progress is rarely steady; rather, it comes about in fits and starts.The Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments were major milestones but they did not end the struggle for voting rights. Subsequent legislation was needed to reinforce or provide additional protections for American citizens.

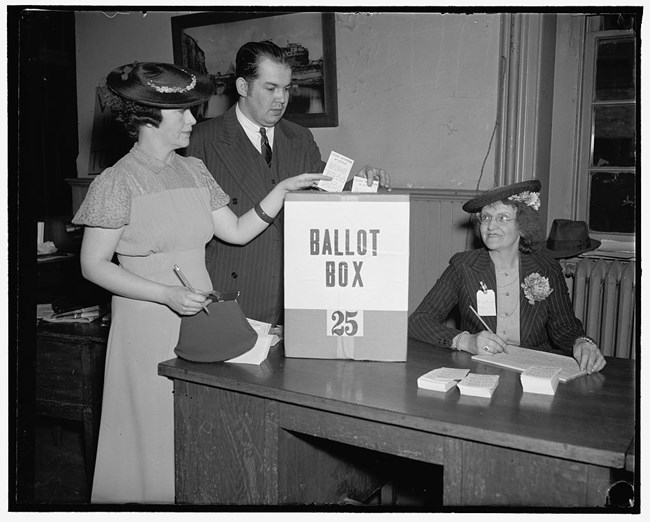

Library of Congress, Harris & Ewing Collection,

https://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/hec/24500/24529v.jpg

One of the most important is the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which addresses the disenfranchisement of African Americans. Beginning in 1890, Southern states adopted laws that made it extremely difficult for African-Americans to vote. These laws required people to pay voting taxes, demonstrate literacy, prove their good character, or perform other challenging tasks, before they were allowed to vote.

Individuals and groups such as the Ku Klux Klan intimidated Black men who had voted or tried to vote with beatings, lynchings, and setting fire to their homes, churches and schools. Because of these laws and threats, African-American voting declined in the South, in spite of the Fifteenth Amendment. For example, 67 percent of Black adult men in Mississippi were registered to vote in 1867, but only 4 percent were registered in 1892. As Black men lost the right to vote, they lost the ability to participate in elections and hold political office. The Civil Rights movement fought these Jim Crow laws and, with the support of President Lyndon B. Johnson, resulted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Throughout the twentieth century, more Americans called for similar protections for their right to vote. For example, Native Americans gained the right to vote when the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 declared that all Indians born in the U.S. and its territories are U.S. citizens. The Twenty-Third Amendment, ratified in 1961, gave American residents of the District of Columbia the right to vote. In 1971, the Twenty-Sixth Amendment lowered the voting age from 21 to 18.

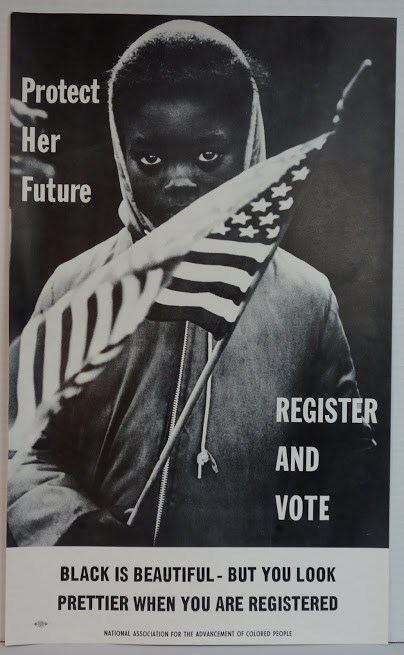

Library of Congress, Posters: Yanker Poster Collection

https://www.loc.gov/item/2016649203/

These changes to voting rights occurred over the course of a century. It takes dedication and persistence to achieve major national milestones like Constitutional amendments. Change happens because of the choices that ordinary people make about how they will use their time, resources, and talents.

Americans believe that the values of democracy, freedom, and equality are worth defending. These values were written into the United States’ founding documents, such as the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, the preamble of which reads:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Each generation of Americans faces a different environment and a unique set of economic, political, and social conditions. When we know this history, we can better understand how far we have come, how we got here, and what our future may hold.

Consider this:

Are you registered to vote? Click here to find resources on registering, voting, and elections.

Part of a series of articles titled Suffrage in America: The 15th and 19th Amendments.

Previous: Voting Rights: Celebrations of Success

Last updated: October 9, 2020