Rosario Dawson: What many history books tell us begins in New York state -- at Seneca Falls -- ends, in a sense in Tennessee.

If the National American Woman Suffrage Association wanted a victory for the whole country, it would need three fourths of the states on board. But that meant winning the South.

Retta: So how easy was this gonna be?

RD: Well just to give you a sense…before 1920, the number of Southern states where women had full voting rights was...zero.

R: Ok so not an easy road.

RD: No. And if you remember, after World War One, President Wilson did finally lend his public support for a federal suffrage amendment. And he was himself a Southern son. But this didn’t move the Southern states. They still passed what they called “rejection resolutions.” These denounced a federal voting rights amendment for women as quote - “undemocratic and dangerous.”

R: Tell us how you really feel.

RD: And yet despite all signs against it, when it came to ratifying 19, the final piece of the puzzle was Tennessee.

How’d they get there? What made Tennessee so special? And what REALLY went on in the Jack Daniels suite?

That’s this episode of And Nothing Less...Episode 6: Southern Discomfort

I’m Rosario Dawson.

R: And I’m Retta.

[Theme]

Spruill: You have worked for 40 years and you will work for 40 years more and do nothing unless you bring in the South.

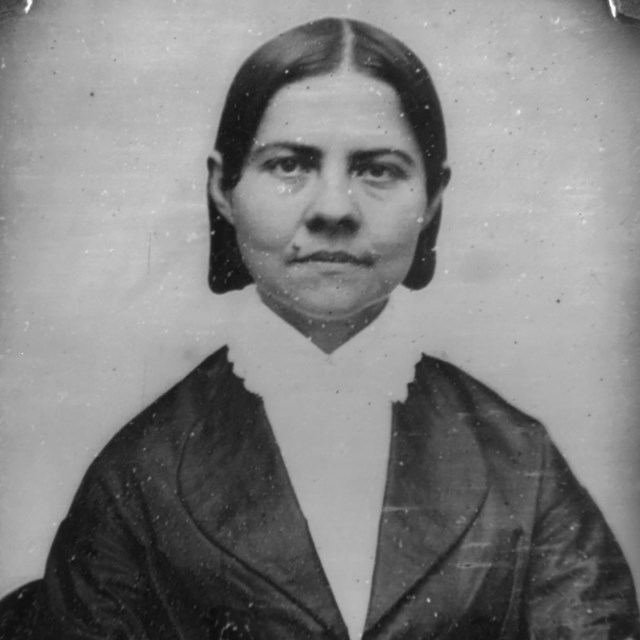

R: That’s Marjorie Spruill reading a warning that Southern suffragist Laura Clay sent to the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1892.

The Kentucky-born suffragist understood that the key to national victory for women was the South. And in some ways the South is also the key to understanding this history. At least Elaine Weiss sees it that way. So much so that she decided to write an entire book on suffrage in Tennessee.

Weiss: So all of the arguments that have been used for the last 70 years, all of the emotions, all of the political maneuvering is crystallized in these six weeks of hand-to-hand political combat in Nashville.

They were not imagining things when they thought if they don't win Tennessee, it might not happen. That momentum might not be with them. And what makes it also so important to analyze what happened in Tennessee is that it is a Southern state and most of the other Southern states had already rejected the 19th Amendment and the reasons that there are several reasons. But the most prominent are states’ rights. The idea of they didn't want the federal government telling them which of their citizens should be able to vote. And of course, that is going to cause problems for the rest of the century in the Southern states and continues to be a problem. And the offshoot of that argument is they don't want black women to vote.

R: Knowing what an uphill battle they would have, for many years national suffrage leadership just avoided the South, says Marjorie Spruill.

Spruill: They knew that the people who had political power in the South after Reconstruction were quite hostile to the woman's suffrage movement. They saw it as a spinoff of the anti-slavery movement, which is actually pretty fair. And so they saw suffragists as radicals. People who had no respect for natural hierarchies and for differences that the white southerners were trying to get people to recognize.

R: But, despite these hostilities, toward the end of the 19th century, more and more southern white women became dedicated to fighting for their rights. Women like Laura Clay, who were in a rarefied position to be able to work as an activist.

It was a white women's movement, largely least a formal organizations were led by white women. Black women were excluded.

These women who took up this cause in the 1890s really had to be from the elite and to have the kinds of protections that elite status gave them. And mind you, this was a rather small group of people.

They had more education. They had travel experiences that help to sort of break down provincial attitudes. And then also to have the leisure time and the money to not only support themselves, but support the movement. And then there was also, the idea that at a time when there was incredible hostility toward the women's suffrage movement, that elite status at least ensured that they would not be ostracized or victims of violence.

R: Laura Clay’s father was an abolitionist and he had been Lincoln’s ambassador to Russia. She would’ve been seen by many as an ideal Southern lady, but with a cosmopolitan worldview.

RD: But while suffragists in the south were progressive about a lot of things, race was not one of them, explains Marjorie Spruill.

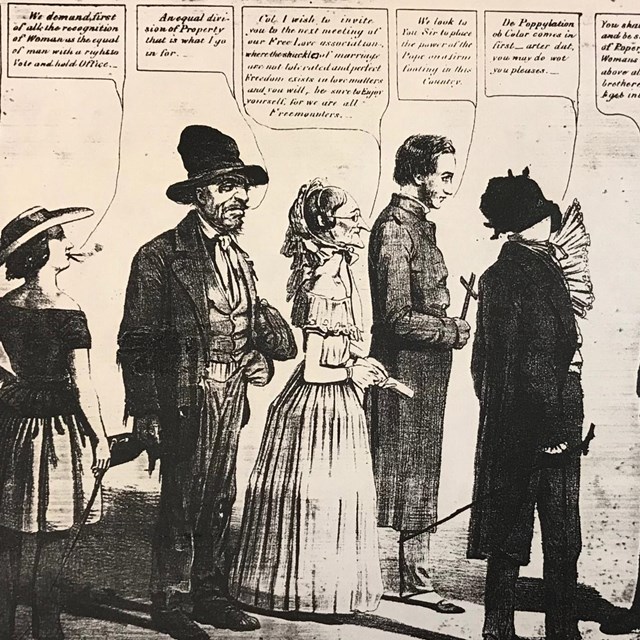

Spruill: The timing of the movement coming to the South had a lot to do with the racial politics of the South. And that in the 1890s they made a pitch for these white Southern legislators to enfranchise women as a way of solving their, quote, Negro problem, unquote. Because what was going on in the at the very time that woman suffragists are pushing for this massive expansion of the electorate. The Southern legislators are pushing really hard to shrink the electorate.

RD: What many Southern lawmakers wanted to do was find a way to somehow get around the 15th amendment.

And remember that’s the law -- coming out of the Civil War -- that protects the voting rights of citizens, regardless of race. But these states knew that if they just ignored this amendment, they’d be punished by Congress.

And so some white suffragists rolled out what Marjorie calls “the southern strategy.”

Spruill: They began to use an argument that ironically originated with Lucy Stone's husband, Henry Blackwell, a former abolitionist.

And that was the idea that the Southern states could enfranchise women. And since there were more white women in the South than African-American, that that would actually help them achieve their goal of restoring white supremacy.

And in fact, if you were to enfranchise women, that there would actually be seen as a liberalisation rather than a restriction of suffrage. And you could then, you know, have the means to preserve white political supremacy without risk.

It was it like pretty much everything else in in setting the south apart as different distinctive from other parts of the country then and now you can just about always trace back in some way to race.

RD: By 1910, however, it was clear that Southern politicians managed to solve the quote - unquote “negro problem” without giving any rights to women.

Spruill: And this particular period was one of the worst periods in the history of race relations in the country.

These newly empowered white conservatives move to drastically expand the Jim Crow agenda and to promote segregation much more than it had been before.

To street cars everywhere. There was already segregation when it came to schools, but it began to be to expand to more parts of the country.

And then there was the massive problem of the increase in the incidences of lynching in the late 19th, early 20th century.

And as the part of the agenda was to so terrorize the black community that they wouldn't challenge a lot of these changes. And so this was a really awful time.

R: And these issues made suffrage even more urgent for black women and men in the south.

While African Americans were largely shut out of the Southern Suffrage Movement, they were fighting for justice, civil rights, and equality in their own clubs.

“Lifting As We Climb,” was the motto of the National Association of Colored Women. And in 1912 it endorsed the women’s suffrage movement. Its president? A southerner named Mary Church Terrell.

Music R: Terrell was born to formerly enslaved parents in Memphis. After graduating from Oberlin College in Ohio, she became the first black woman to earn a position on the Board of Education in Washington D.C. But she never forgot her Southern roots, especially when it came to what motivated her about suffrage and justice.

In Memphis, Terrell and Ida B. Wells were both friends with a man named Thomas Moss. And in 1892 he and two business partners were lynched by a white mob.

Alison Parker: For both of these women, this 1892 lynching was a traumatic and a transformational event.

R: Alison Parker teaches history at the University of Delaware and is the author of an upcoming biography of Terrell called Unceasing Militant.

Parker: For Ida B. Wells, for many years, it turned her into quite singularly an anti-lynching activist. The same exact time that she became mobilized into action because of this, Mary Church Terrell was pregnant and living in Washington, D.C. and had a miscarriage. And she believed that her illness and her miscarriage was in part from the trauma that she experienced, learning about the death of her friend Thomas Moss in such a brutal way.

R: According to Parker, dealing with her family and her health crisis made it impossible for Terrell to focus all of her attention on anti-lynching.

Parker: She instead joined what was called the Colored Women's League of Washington, D.C., and started doing activism in terms of things like kindergartens and nursery schools and daycares and other kinds of institution building for black children and black women and men that were lacking because these kinds of institutions did not exist in the wider culture as provided for by, let's say, the District of Columbia.

RD: In her visits back to Tennessee and other southern states, Terrell noted the kinds of tactics that white suffragists were using. And despite early unity and talk of “votes for all”, when it came to the final push to ratify the 19th amendment in 1919 and 1920, the women’s rights movement was deeply divided, especially on the subject of race.

Lisa Tetrault: The movement never unifies, which is an interesting thing, you'd think you'd need a unified movement to create a victory.

But in fact, you don't. You just need sufficient pressure and sufficient luck.

RD: Lisa Tetrault is a professor of history at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. You remember her from our myths episode.

Tetrault: There are so many different factors that lead to the passage and the ratification eventually of the 19th Amendment. But one of them, I think we neglect to our peril is the ways in which the states were remaking democracy in the decades leading up to the 19th Amendment that I think made the 19th amendment more palatable to many to many white men who eventually agreed to vote for it.

Congresspeople are willing to vote for it because they realize the women they don't want voting. Often women of color will be ensnared in these other restrictions so that if they pass the 19th Amendment, it will be largely white women who get access to the ballot, not only, but largely because they won't have these other things ensnaring them.

RD: And this was the agreement when it came to finally getting the 19th Amendment passed. The Southern lawmakers needed to know that black women still wouldn’t be able to vote. And the suffrage movement assured them of it.

[Music]

RD: We’ll be back.

//

BREAK

//

[Music]

RD: We’re on Episode 6. Which means we’re not too far from the end of our race to ratification. Where exactly are we on our timeline?

R: Well, if you remember from our last episode, the Silent Sentinels began their public protests outside the White House in 1917. Their banners asked: MR. PRESIDENT, HOW LONG MUST WOMEN WAIT FOR LIBERTY?

R: And the women returned again and again. They were arrested and jailed, over and over again. Each time, their treatment would get worse and worse. Alice Paul and others began hunger strikes, and in response, some were violently force-fed. This lasted months, and you have to remember the country was also in the midst of a war. This was a public relations nightmare for the White House.

R: Finally, in late November of 1917, the suffrage prisoners were released. And in January 1918, President Wilson made his public announcement of support in favor of a federal amendment. And the next day - the House passed the suffrage amendment. But it fails in the Senate.

So the fight goes on for another year. Members of the National Woman’s Party light Watchfires for Freedom in front of the White House until the following Spring of 1919 when suffrage finally gets another chance.

R: And what exactly are watchfires?

RD: Retta, this is actually kind of a cool detail. This is when the suffragists would burn copies of the President’s speeches, making essentially a cauldron right outside of the White House Fence. Witchy, right?

R: I’m gonna have to remember that.

RD: So we’re in the Spring of 1919. Watchfires ablaze. And on May 21, 1919, the House once again passed the 19th Amendment. And this time, the Senate did too. On June 4, 1919, Congress finally passed the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. That’s what people had started to call it by then.

That left three-fourths of the states to ratify it. Back then that was 36 states of the 48 we had at the time.

R: Some states like Michigan and Wisconsin came quick and easy. California and Maine took a few more months. But the South? Well almost all of the Southern states rejected the 19th Amendment. Many using the usual rationales - states’ rights and racism.

RD: When Washington State finally came aboard in March 1920, that brought the ticker up to 35 states. Only one more was needed.

Certainly anything would have to be easier than a state in the South. But after Delaware rejected the amendment in June 1920, Tennessee became the best and only option, according to Marjorie Spruill.

Spruill: They were the only ones that were going to have a special session before the November 1920 election. RD: Now, this may seem like a small point -- but it was actually a HUGE hurdle that the suffragists had to overcome. Elaine Weiss explains --

Weiss: At the time, 1920. Many legislatures did not meet every year in full session. Some met only every two years. And one of the things of the Senate that those senators in the U.S. Congress who were opposed to granting women the vote, they delayed the passage through Congress with the understanding that if it came out in 1919, it would come out in it in a time when most states, their legislatures would not be in session.

RD: This meant that the suffragists would have to convince 30 governors to call their legislature BACK to the Capital to act on ratification….

R: [sarcastically].... Good luck with that!

Spruill: This was a big hurdle because a lot of governors complained, well, it's expensive. We have to pay per diem. We have to pay their transportation. We have to pay for secretaries and stenographers. And the suffragists said we'll pay for it. We'll pay for it. Well, well, we’ll act as stenographers. We'll be chauffeurs. We'll do anything. Call them back.

Some governors were afraid that when you call a special session, even if you say it's just to act on ratification of the 19th Amendment, other bills and other topics can be brought up. And some of the governors feared that there would be things they didn't want to have to deal with would come up in the legislature.

A few of the governors even feared they might be impeached if the legislature was called back. So in some cases, the suffragists really have to turn the screws to convince the governors to call a special session. And we see what happens in Tennessee. They have to work very hard. They have to put a lot of pressure. And even the White House gets involved in pressuring the governor to call a special session, he doesn’t want to do it.

And then, of course, they have to lobby. They have to lobby the legislatures.

RD: And Carrie Chapman Catt, the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, comes down to Nashville from New York to manage the strategy. And she wasn’t feeling great about it.

Weiss: Oh, she was miserable.

RD: Well this is Nashville in August after all. Here again is Elaine Weiss.

Weiss: She realizes that Tennessee could be the pivotal last state or it could be the beginning of the end of the momentum.

And then Alice Paul sends her lieutenant, Sue Shelton White, to run the Woman's Party campaign for Tennessee ratification. So you have two women's groups with the exact same goal, but totally different strategies, different staffs, separate headquarters and some real friction between them. And it teaches us something about how movements don't always work in in perfect harmony.

RD: And Elaine Weiss says you have to wonder if this friction helped or hindered the cause?

Weiss: I'm of the school that thinks that it needed both of those approaches. But Carrie Catt at this point is 62 years old. She's devoted at least 30 years of her life to suffrage at the highest levels. Her name is synonymous with the movement. And yet she sees her cause up for this really definitive fight. And she also sees her own legacy at stake. So she's a rather nervous leader as she arrives in Nashville. And she'll be kept in almost house arrest. She'll be kept in her quarters in the Hermitage Hotel because as a northerner, she is not welcome in Tennessee. And so she has to not show her face all that much. And-she is, you know, by the end by that last night before the vote, she is in perfect despair. She sees the political reality, a road, the advantage that she came in with. It's very painful.

R: One woman who would not make Catt’s stay in Nashville any more comfortable was Josephine Pearson. Even before Catt stepped off the train, Pearson’s colleagues warned her via telegram that they must be ready:

“Our forces are being notified to rally at once. Send orders - and come immediately.”

As the president of the Tennessee State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage AND the head of the state division of the Southern Woman’s League for the Rejection of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, she was more than prepared for the task.

Weiss: Josephine Pearson is just one of those fascinating women.

She is the most well-educated woman in the entire cast of characters. She has graduate degrees. She is a political science professor at small Christian women's colleges.

But she also comes out of the milieu that the religious milieu and the social milieu of Tennessee at the time. And she her mother was against the idea of women's suffrage. And there's a religious aspect that this goes against God's plan. It's very wrong. And there's also the social part that this is going to emasculate American men and make more masculine American women.

And so she convinces herself and convinces others that there are intellectual and social and moral reasons that women should not get the vote.

R: And her goal, writes Elaine Weiss, was to make Catt the living symbol of all that was alien and evil, ungodly and un-American, Bolshevik and detestably Yankee.

If that sounds like dirty politics, you ain’t heard nothing yet, according to Elaine Weiss.

RD: Like what?

R: Well, she says in the final weeks of the fight in Nashville there was booze, bribes and blackmail. Fistfights and kidnappings, betrayal and courage.

Spies roamed the hallways of the Hermitage Hotel, where both sides set up shop. And lawmakers at the Capitol buildings got fake telegrams. Weiss reports that the newspapers called it “Suffrage Armageddon.”

[Music]

Weiss: We begin with the governor, who is no friend of women's suffrage. He opposed it when he ran for election. He wants to avoid it at all costs. He's up for reelection in the fall. This is the last thing he wants is a fight over women's suffrage. And so he tries to duck at every opportunity and finally gets where it's cornered by not only the suffragists, but also by President Wilson and is forced to call the legislature back into session.

Then we have someone like the speaker of the House, Seth Walker, this very young, strapping. He's only 28 years old. And he is willing to be persuaded by, shall we say, less than sterling motives.

Bribery is a big theme in this in this story. And we see him change sides and betray the suffragists in a very dramatic way.

And then we have some fascinating men in the legislature who we see evolve. We see changed their minds sometimes for nefarious reasons. We see them being persuaded by what's called the liquor lobby. Again, that manufacture and sale of liquor has been prohibited, Prohibition’s in effect in the summer of 1920. But the liquor lobby is still trying to fight against women voting because they're hoping that if they can keep women away from the ballot box, even though Prohibition’s in effect, that it won't be enforced stringently as the law provides for. They establish one of the more comical aspects of the fight, which is they the set up a 24/7 speakeasy on the eighth floor of Hermitage Hotel where everybody's staying and they ply the legislators with liquor, especially Tennessee's favorite liquor, Jack Daniels.

It's called the Jack Daniels suite. And this is kind of hospitality suite where the legislators go to get drunk and to listen to reasons why they should not ratify the amendment. And there are great scenes of the legislators singing in the hallways and bouncing off the walls, and they have to be thrown into the showers before they can sober up to go in to vote. And Carrie Catt says it's this this the entire legislature drunk at it's told very matter-of-factly. Oh, yes. That's how we make big decisions here.

[Music playing underneath]

RD: The outcome of this big decision, which would change the outcome for women in the entire country, was in doubt, until the very last minute.

On the night before the final vote, the suffs were sure they did not have the votes. Even Carrie Catt said “we can only pray.”

And in the end, it came down to one single vote by the youngest member of the Tennessee House of Representatives. You remember, Harry T. Burn, from our first episode? With his red rose, but more importantly with his very persuasive letter from mom? Thanks to Burn’s tie-breaking vote, Tennessee ratified the suffrage amendment with 50 ayes.

On August 18, 1920 those 50 men agreed to this:

“The right of the citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

As the 36th state, Tennessee was the final one needed to ratify the 19th amendment into the U.S. Constitution. It was a longer and uglier battle than anyone had expected.

Days later, the Chattanooga Daily Times wrote, “Today the women and men who have won the struggle can look back with gratitude to the work of the courageous pioneers whose sole rewards were discouragement and ridicule.”

Women like Carrie Catt and Sue White.

R: But in the South, for so many women, this is only a partial victory. Mary Church Terrell, for example, would not be able to vote in her native state, Tennessee, in her lifetime.

Weiss: If you truly believe that we are a democracy, that we have created a government for and by the people.

If you accept that this is a nation based upon we the people. Then how do you justify that half of the nation was deprived of any voice in their government, deprived of the vote for 150 years. And then even after the 19th Amendment rectifies that egregious omission of the founding fathers. How do you explain that it will take another four decades, at least for African-American citizens in the Southern states. And this is not across America because in the North and the West and the Midwest African-American women and men could vote. But in the Southern states, they still are not able to exercise their constitutional protections because of Jim Crow laws. So how do you explain that?

And it takes, again, decades for subgroups to be given the vote or at least to be able their vote protected by the Voting Rights Act.

R: And one of the opportunities of this anniversary, says Elaine Weiss, is that we can look at how to fulfill the potential of this extraordinary social and political movement. Its failings, its successes and the work that still needs to be done, when it comes to empowering women and people of color.

[Fade up music]

And we’ll talk more about that - 1920, the victory and the aftermath - on our final episode of And Nothing Less. I’m Retta.

RD: And I’m Rosario Dawson

This was And Nothing Less, from the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission and PRX. This podcast was envisioned by W-S-C-C Executive Director Anna Laymon with support from Kelsey Millay.

The production team is Executive Producer Genevieve Sponsler, Producer & Audio Engineer Samantha Gattsek, and Writer & Producer Robin Linn. Our music is by Erica Huang.

The historical content used to create these stories was brought to you by the National Park Service -- teachers can download companion lesson plans at go.nps.gov/suffragepodcast.

Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt Mary Church Terrell

Mary Church Terrell Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Ida B. Wells-Barnett Harry T. Burn

Harry T. Burn Dr. Alice Paul

Dr. Alice Paul Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone Occoquan Workhouse

Occoquan Workhouse Hermitage Hotel, Nashville, Tennessee

Hermitage Hotel, Nashville, Tennessee The Places of Carrie Chapman Catt

The Places of Carrie Chapman Catt Woman Suffrage in the Southern States

Woman Suffrage in the Southern States Anti-Suffrage in the United States

Anti-Suffrage in the United States African American Women and the 19th

African American Women and the 19th Silent Sentinels

Silent Sentinels The Necessity of Other Social Movements

The Necessity of Other Social Movements Lobbying for Suffrage

Lobbying for Suffrage Suffrage in 60 SecondsDeadly Political Index

Suffrage in 60 SecondsDeadly Political Index Suffrage in 60 SecondsNAWSA vs. the NWP

Suffrage in 60 SecondsNAWSA vs. the NWP Suffrage in 60 SecondsHarry Burn

Suffrage in 60 SecondsHarry Burn Suffrage Asks Tennessee to Vote

Suffrage Asks Tennessee to Vote Josephine Pearson at Anti-Suffrage HQ

Josephine Pearson at Anti-Suffrage HQ Tennessee Senate Chamber

Tennessee Senate Chamber