Preservation laws, ranging from the National Historic Preservation Act to state and local ordinances, play an important role in protecting historic places. So do the community groups and individuals who advocate for the historic places that are meaningful to them. Together, they can do a lot to protect the places that express our history and heritage. The examples below show both successes and failures in historic preservation. When sites are lost, it is sometimes because the laws at the time were not set up to protect a historic place, such as the Garrick Theater. Other times, commercial pressures proved insurmountable, such as with the Univision Building. The loss of an important place may have a silver lining, by creating stronger community support for historic preservation that can save other valuable places.

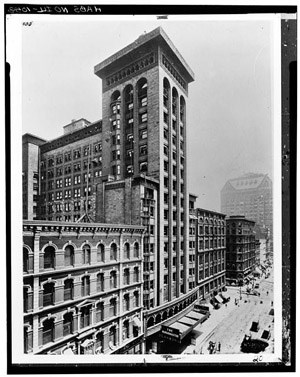

NPS/Historic American Buildings Survey

Lost: Garrick Theater

Documented for the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS IL-1058), 1961.

Demolished, 1961.

Chicago's Garrick Theater was built in 1891 as a lavish opera house for the German Opera Company. Designed by Adler & Sullivan and known originally as the Schiller Theater, it was among Chicago's most acclaimed architectural treasures.

But by 1960, with urban renewal in full swing, the Garrick's grandeur had faded considerably. "Cheap rents," writes author Richard Cahan, "attracted private detectives, phrenologists, and ne'er-do-well attorneys." There had been successive bad remodels, the ground floor occupied by a Ham n' Egger restaurant. But beneath all that, Sullivan's vision could still be seen.

The Garrick had the architect's signature colonnaded arches and terra cotta on its outer face, which gave the effect, in Cahan's words, of "a fluid, undulating skin." The theater itself, which started in the waning days of opera and then became a prominent venue for vaudeville, was surrounded by offices. When it was scheduled for demolition, an outcry ensued.

Local photographer Richard Nickel began photographing the Garrick Theater inside and out, trying to capture its beauty in advance of the wrecking ball. Though Chicago had formed a landmarks commission in 1957, it was largely ineffective. Nickel appealed to the media and to the mayor's office. Scholars, architects, and curators from around the world protested the impending destruction of the building. Frank Lloyd Wright's widow sent a letter to Mayor Daley.

The Garrick was suddenly a hot topic. Daley had a hearing in the city council chambers, with the developers denied a demolition permit while alternatives were considered. The developers sued. The building's fate hung in the balance for months, but in the end it was torn down, the wreckage laid out in a giant shed at Chicago's Navy Pier, including the plaster ornaments and pieces from the proscenium of the theater.

While the Garrick Theater was lost, the fight over its demolition signaled an increasing awareness of Chicago's past. The city would lose more landmarks in the ensuing years, but people were paying attention now. The loss of the Garrick was a step on the path to the creation of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 and Chicago's Landmarks Ordinance.

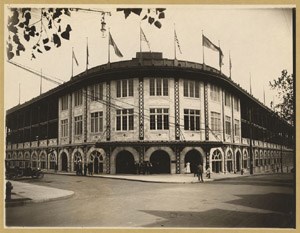

Library of Congress

Lost: Forbes Field

Demolished, 1971.

In the revered tradition of neighborhood ballparks, Pittsburgh's Forbes Field was one of the greats. Built in 1909, it was among the first made of concrete and steel, signaling the end of the old wooden stadiums. In a city known for its work ethic, Forbes Field bespoke a serious approach to leisure. The exterior was elaborate, the outfield vast. A review of the time stated, "For architectural beauty, imposing size, solid construction, and public comfort and convenience, it has not its superior in the world."

The stadium was home to the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1909 to 1970. In the summer of 1921, it was the site of the first radio broadcast of a major league game. It was here that Babe Ruth hit his final home run. In later decades, a new generation of fans thrilled to the heroics of Roberto Clemente and his teammates; Forbes was the scene of one of the game's immortal moments, when the Pirates' Bill Mazeroski hit a home run to win the thrilling 1960 World Series in game seven against the Yankees. The University of Pittsburgh's towering Cathedral of Learning served as an observation deck for fans on the outside.

At the dawn of the 1970s, big changes in the steel industry were underway, and Pittsburgh faced an uncertain future. Almost as a ritual goodbye to the past, Forbes Field was demolished, replaced with a high tech arena with Astroturf at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers. Three Rivers Stadium was part of the multi-purpose megastadium wave of the 1970s. Like Forbes, these giants were eventually considered obsolete, most demolished for parks trying to recapture the character of the old fields. As a reminder of a time long gone, parts of Forbes Field have been preserved. The flagpole, home plate, and parts of the ivy-covered outfield walls remain on what is now the University of Pittsburgh campus.

Jimmy Emerson, DMV (Flickr). Photo shared with a Creative Commons license.

Saved: Granada Theater

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, 1985.

Built in the grand style of its day, the Granada Theater of Emporia, Kansas, was the work of the Bowler Brothers, nationally known theater designers. The ornate Spanish Colonial Revival structure, erected in 1929, screened first-run films and hosted vaudeville acts and beauty pageants. But by the '60s, it was in decline, closing in 1982.

Its listing in the National Register of Historic Places was the first step in a comeback, culminating in a three-year, $2.6 million campaign launched by the Emporia Granada Theatre Alliance. Today, with the help of the National Park Service-administered preservation tax credit program, it once again draws crowds, its decorative plaster and terra cotta fully restored. New terraces on the main floor allow for seating flexibility to accommodate not only movies, but concerts, conferences, wedding receptions, and dinner theater. Local arts and cultural groups have joined to make the Granada a force in revitalizing downtown Emporia.

National Park Service/NHL Program

Saved: Farnsworth House

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, 2004.

Designated a National Historic Landmark, 2006.

Documented for the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS IL-1105 series), 2009.

The Farnsworth House, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's modernist masterpiece, is a glass and steel structure on a wooded lot in rural Illinois. It was unprecedented in its day and continues to challenge conceptions of how domestic spaces relates to its natural setting.

There were several concerns about the auction, one that the building's small size and relatively simple construction might encourage an owner to disassemble and move it elsewhere. Since the context is so much a part of the design, this would have been an irreparable loss.

The Fox River runs along the property and while the architect could have chosen to build on higher ground, he instead immersed the structure in its wooded setting. Van der Rohe produced something that was revolutionary for its time: a 1,400 square-foot living space that has the appearance of a single room whose boundaries with the outside fade to nearly nothing. Floor-to-ceiling windows enhance the effects, as do the slender steel beams and columns. Interior supports are concealed in the arrangement of a closet, bathroom, and fireplace enclosure, all encased in wood to harmonize with the setting. The design was an attempt to alleviate what Van der Rohe saw as the alienating effects of techno-industrial society.

The Friends of the Farnsworth House had lobbied the state to purchase the house and though several million dollars were appropriated for that purpose, the deal never went through. Now under ownership of the Trust, it is operated as a museum by Landmarks Illinois. It is open to the public and its resource center is a repository of information about the groundbreaking creation with books, periodicals, photographs of the construction and original furnishings, and an interactive tutorial on Mies van der Rohe's career. There are also oral histories—available on DVD—from people who were involved with the project.

National Park Service/TULE

Saved: Internment Camp at Tule Lake

Documented for the Historic American Buildings Survey (various survey numbers), 1988 and 1997.

Designated a National Historic Landmark, 2006.

Proclaimed a National Monument, 2008.

As a relic of the fear and prejudice that prevailed in the wake of Pearl Harbor, the internment camp at Tule Lake has no equal. Of the 10 camps built during WWII, the sprawling northern California complex was the focal point of dissent and a stage where the consequences of internment played out. For that reason—and because of its exceptional state of preservation—Tule Lake was designated a National Historic Landmark, placing it among the most revered places in America.

Little has changed since the end of the war. Barbed wire fences still trail through the open fields. The foundations of the guard towers are visible in the tall grass, and many structures remain.

As in all the camps, the transition from freedom to confinement was a shock. Communal bathrooms, crowded mess halls, and barracks with little privacy disrupted traditional family life. Parents felt that they were losing control of their children.

Within five months of the camp's opening there was a strike to protest the food. This was followed by other strikes over work arrangements and living conditions. Trouble escalated when the authorities produced a questionnaire intended to gauge the loyalty of the detainees and their suitability for the draft. Many answered no to military service to keep their families together. A question asking if they would repudiate Japan was seen as a trick, since first generation Japanese-Americans could not become citizens and feared that a yes answer would leave them without a country.

The result was that the Army determined that many of the internees were disloyal and Tule Lake was turned into a maximum security prison. Strife mounted and there were soon incidents of violence not only between internees and guards, but among the internees themselves.

In 1944, President Roosevelt signed the "denationalization bill," which allowed internees to renounce their U.S. citizenship. Many did, seeing it as the only way to avoid the draft and the breakup of their families. When the war ended, many found themselves awaiting deportation. The irony was that those who had chosen America as their home now faced the prospect of starting over in a devastated Japan. Civil rights attorney Wayne Mortimer Collins took up their cause, engaging the Justice Department in a long fight to restore the internees' citizenship, which was finally won.

Today, the National Park Service is working with the state of California to protect the remaining buildings at Tule Lake. Former internees and community activists began organizing pilgrimages in 1974, partly as a way to educate the public that seemed to have forgotten. The pilgrimages continue today.

Lost: Univision Building

Demolished, 2013.

Residents watched with great sadness when the Univision Building, a mid-20th-century modern structure in downtown San Antonio, was demolished. The building was home to the very first Spanish-language television station in the United States and was a great symbolic importance to the area's Latino community.

The Univision Building is a good example of how a place can exceed its architecture and embody cultural experience. For San Antonio's Latino community, the building played an important role in civil rights and served as a landmark of the city's Mexican-American heritage.

KCOR founder Raoul Cortez, a Mexican-American, started the station in 1955. The Spanish-language production was successful even though one of three households in America did not own a television. The Univision Building gave a sense of identity and an affirmation of the Latino community. It was also one of the few mid-century modern designs in downtown San Antonio.

The building was torn down to make way for a $55 million luxury apartment complex. Residents and activists fought to save it and even got a judge to temporarily issue a restraining order on its demolition. But in the end, the project went ahead and the Univision Building was lost.

There is hope that this event will begin a broader conversation about San Antonio's historic structures and what they mean, particularly to Latino communities. Said Tanya Bowers, director of diversity at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, "If anything, this occurrence reinforces the need for more education."

Last updated: November 1, 2023