NPS / Gavin Emmons California condors, once widespread across the western United States, are just beginning their comeback into parts of their historic range. The Sierra Nevada mountain range has not seen the distinctive wingspan of a condor for the better part of 30 years, but today that is changing.

USFS / Allen Love Currently, there are no condors nesting in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, but they occasionally fly through the area. Since reintroductions began in the 1990s, sightings of condors have been reported throughout the parks, with a few officially confirmed. In 2014, four condors landed on the railings of the Buck Rock Fire Tower just outside the parks in Sequoia National Forest. And as recently as 2020, four condors were sighted flying over the Giant Forest, two of which landed in mountainous terrain. Through recent years, many more reports of condors, including those being tracked by GPS and radio transmitters, have been made of birds flying very close to or just into these national parks.

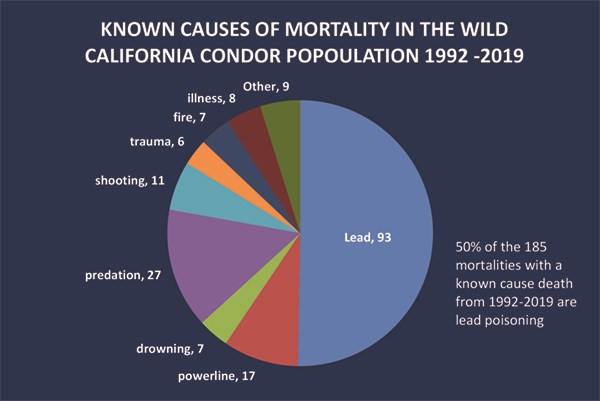

Source: California Condor Recovery Program 2019 Annual Population Status, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service The recovery of the California condor continues to move forward with success stories across the Western United States. We at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks look forward to a future where visitors can come here and not only see some of the largest trees, deepest canyons, and tallest mountains on earth, but also but also some its largest birds, including one that came back from the very brink of extinction. |

Last updated: July 2, 2020