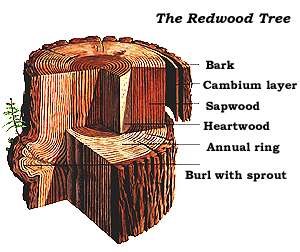

Superlatives abound when a person tries to describe old-growth redwoods: immense, ancient, stately, mysterious, powerful. Yet the trees were not designed for easy assimilation into language. Their existence speaks for themselves, not in words, but rather in a soft-toned voice of patience and endurance. From a seed no bigger than one from a tomato, California's coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) may grow to a height of 367 feet (112 m) and have a width of 22 feet (7 m) at its base. Imagine a 35-story skyscraper in your city and you have an inkling of the trees' ability to arouse humility. Some visitors envision dinosaurs rumbling through these forests in bygone eras. It turns out that this is a perfectly natural thought. Fossil records have shown that relatives of today's coast redwoods thrived in the Jurassic Era 160 million years ago. And while the fantastic creatures of that age have long since disappeared, the redwoods continue to thrive, in the right environment. California's North Coast provides the only such environment in the world. A combination of longitude, climate, and elevation limits the redwoods' range to a few hundred coastal miles. The cool, moist air created by the Pacific Ocean keeps the trees continually damp, even during summer droughts. These conditions have existed for some time, as the redwoods go back 20 million years in their present range. Growth Factors Resistance to natural enemies such as insects and fire are built-in features of a coast redwood. Diseases are virtually unknown and insect damage insignificant thanks to the high tannin content of the wood. Thick bark and foliage that rests high above the ground provides protection from all but the hottest fires. The redwoods' unusual ability to regenerate also aids in their survival as a species. They do not rely solely upon sexual reproduction, as many other trees must. New sprouts may come directly from a stump or downed tree's root system as a clone. Basal burls — hard, knotty growths that form from dormant seedlings on a living tree — can sprout a new tree when the main trunk is damaged by fire, cutting, or toppling. Undoubtedly the most important environmental influence upon the coast redwood is its own biotic community. The complex soils on the forest floor contribute not only to the redwoods' growth, but also to a verdant array of greenery, fungi, and other trees. A healthy redwood forest usually includes massive Douglas-firs, western hemlocks, tanoaks, madrones, and other trees. Among the ferns and leafy redwood sorrels, mosses and mushrooms help to regenerate the soils. And of course, the redwoods themselves eventually fall to the floor where they can be returned to the soil. The coast redwood environment recycles naturally; because the 100-plus inches of annual rainfall leaves the soil with few nutrients, the trees rely on each other, living and dead for their vital nutrients. The trees need to decay naturally to fully participate in this cycle, so when logging occurs, the natural recycling is interrupted. Understory Perhaps the most famous and spectacular member of the redwood understory is the brilliantly colored California rhododendron. In springtime, the rhododendrons transform the redwood forests into a dazzling display of purple and pink colors. Role of Fog Fog precipitates onto the forest greenery and then drips to the forest floor, providing a small bit of moisture during summer dry periods. Fog accounts for about 40 percent of the redwoods' moisture intake. Root System Large redwoods move hundreds of gallons of water daily along their trunks from roots to crown. This water transpires into the atmosphere through the trees' foliage. Powered by the leaves' diffusion of water, water-to-water molecular bonds in the trees' sapwood drags the moisture upwards. During the summer, this transpiration causes redwood stems to shrink and swell with the cycles of day and night.

NPS |