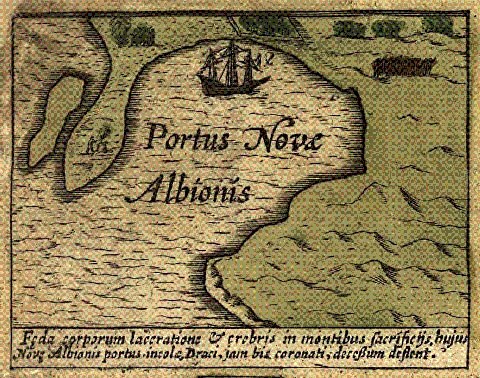

Public domain. Francis Drake's "Harbourgh"Perhaps no event in California's history has been as thoroughly debated as the landfall of Francis Drake's Golden Hind in 1579. His visit to a "convenient and fit harbourgh" has been narrowed by conjecture and evidence to at least three locations near Point Reyes. The evidence, the chaplain's diary, and shards of delicate porcelain—part of Drake's treasure—leads most scholars to the estuary and bay along the southern coast of Point Reyes peninsula which bear his name today. Drake's Early YearsDrake's landing in California was part of a much larger trip—"The Voyage of Circumnavigation"—in which he sought the Strait of Anián, the fabled Northwest Passage linking Europe to the rich lands of the East Indies via a route to the north of the Americas. It was a time of empire building for England, which trailed the earlier explorations and colonial expansion of its chief rival, Spain. His early years among the ships of the Thames Estuary were marked by the intensely emotional turmoil of the Protestant Reformation, which governed not only Europe's spiritual life, but also its political life. Drake's quest for new lands and riches took him on many voyages across the Atlantic. During his first three trans-Atlantic voyages, he sailed with John Hawkins, his second cousin and the man who is considered to have been the first English slave-trader. In 1568, during the third expedition, Hawkins' fleet was attacked by Spanish warships for engaging in illegal trade in the Caribbean Sea, including trading enslaved people. Hawkins lost four of six ships, and he and Drake narrowly escaped death. This event was a catalyst for Drake's hatred of Spain and preceded the many battles he waged against the Spanish. It was during his fourth trans-Atlantic voyage, in 1572, that Drake is said to have climbed a tree on the Isthmus of Panama and first glimpsed the Pacific. Captivated by this view, he swore to sail an English ship to those waters. The Start of the "The Voyage of Circumnavigation"Drake made good on this oath when he sailed from Plymouth in 1577 with a fleet of five ships and headed west amidst storms and mutiny. He reached the Port of St. Julian on the Argentinean coast in mid-1578 and overwintered there before rounding South America. Ferdinand Magellan, the first explorer to circumnavigate the globe and whose global sailing record would be eclipsed by Drake, had similarly overwintered in the harbor in 1520. Reaching the Pacific in September of 1578, Drake continued north, seeking the Northwest Passage and striking at ships and ports along the western coast of South America, a significant source of Spain's colonial wealth. His ship, the Golden Hind (which had originally been named the Pelican), was soon bulging with gold and silver, chests of rare porcelains from China, spices, and silks. Drake continued sailing north, moving further and further from the familiar and charted waters of Panama and Mexico. His northward search for the Northwest Passage is thought to have ended around 42 degrees north, near the current Oregon-California border, although some accounts have argued he may have reached what is now British Columbia. He then turned southward, the Golden Hind having sprung a leak that needed repair. By June 17, 1579, he had slipped southward to 38 degrees with the ailing ship, anchoring in the first calm waters he could find.

Public domain. Where was Nova Albion?While Drake spent only six weeks in this harbor, repairing and preparing the Golden Hind for the long voyage west across the Pacific, healthy debate among history buffs as to the exact location of the harbor has lasted centuries. The log of the voyage, complete with Drake's own watercolors, was presented to Queen Elizabeth I and declared the Queen's secrets of the Realm. Drake and his crew were sworn to secrecy upon pain of death, lest the Spanish might learn of Drake's activities. The diary of the ship's chaplain, Francis Fletcher, and interviews with Drake's cousin, John Drake, are the chief sources on what we now know about his visit to California. From their descriptions, it appears that the anchorage was the estuary that now carries Drakes name on the Point Reyes peninsula. Chaplain Fletcher noted the light colored cliffs near the estuary, which reminded the sailors of the white cliffs of Dover. He noted the "stinking fogges," which would be typical of summer weather on the Point Reyes peninsula.

Public domain. The Coast MiwokThe native inhabitants of the area greeted Drake's crew and, from examining the descriptions of these people, anthropologists have identified the Coast Miwok people of what in now Marin County as the people with whom Drake encountered. The Coast Miwok are thought to have believed these pale-skinned people from the sea were the spirits of their dead ancestors. They came often to visit the small encampment Drake had built while he completed his repairs, and it is thought that Drake gifted them with Chinese porcelains. The Plate of BrassOnce the repairs to the Golden Hind were completed, Drake claimed the land for England by setting up a stout post to which he nailed a metal plate engraved with his declaration and a sixpence and named the land Nova Albion. In 1936, a brass plate was found in Marin County at Limantour Beach. Historians believed that this plate, which carried a similar text as recorded from Chaplain Fletcher's diary, was final proof that Drake landed in Marin. However, the plate did not withstand the tests of time or science. Modern testing confirmed that the plate could not have been manufactured with the technology available to sailors in the late 1500s and must have been created much later. It wasn't until 2002 that the origin of the fake plate was finally uncovered. Today, the plate can be found in the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley as an object lesson in how hoaxes can be accepted as fact. PotsherdsWhile the original metal plate has yet to be found, the delicate blue and white Chinese porcelains given to the Miwok has provided modern scholars with additional evidence of the site of Drake’s Nova Albion. Over the years, bits and pieces of porcelain have been recovered from the beaches of Drakes Bay and nearby Miwok archaeological sites. Close inspection by the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco in the 1990s found that some of the pieces were scratched and worn as if tossed along sandy beaches. Other bits had sharp, unworn edges and had mostly been recovered from archeological sites. The worn pieces are believed to be from the San Agustin, a Spanish galleon that wrecked in Drakes Bay in 1595, while the sharp-edged, unworn shards are thought to be from Drake's earlier gifts to the Miwoks in that foggy June of 1579. Completing "The Voyage of Circumnavigation"Drake continued across the Pacific to Indonesia and then around Africa's Cape of Good Hope, completing the last leg "The Voyage of Circumnavigation" as he returned to England. The Golden Hind, bulging with treasures from the East Indies, arrived in Plymouth in September of 1580. In 1581, Queen Elizabeth I knighted Drake on board the Golden Hind in recognition of this journey. Sir Francis Drake continued a career of service to his queen, serving as Mayor of Plymouth and a Member of Parliament in the early 1580s before returning to the sea in 1585 to raid Spanish settlements in the Caribbean. Drake's Later YearsThrough the spring of 1586, Drake raided and plundered many Spanish colonies in the Caribbean before heading north along the Atlantic coast of North America. In June of 1586, Drake arrived at Roanoke Island in what is now North Carolina. There he found a 115-man English military detachment that had arrived there in 1585, at what is now Fort Raleigh National Historic Site. The military colony was on the brink of starvation and were anticipating an impending Algonquian attack. Drake had arrived just in time to rescue and transport them back to England. He didn't get to stay home long before he was dispatched by Queen Elizabeth I to lead an attack on the Spanish fleet at Cadiz in 1587. The expedition was a military success, with over one hundred Spanish vessels destroyed or captured and delaying King Philip's plan to launch his armada to invade England by a year. When the Spanish Armada did launch in 1588, Drake helped lead the successful defense of England as vice admiral in command of the English fleet. This victory helped pave the way for England to become a global superpower and helped Drake secure a reputation as one of the finest sailors in history. However, the defeat of the Spanish Armada was among the last of Drake's successful ventures. An expedition to attack Spain failed in 1589. He returned to the Caribbean in 1595, where he suffered many defeats, including the Battle of San Juan, which occurred on November 22. Castillo San Felipe del Morro (El Morro), now part of San Juan National Historic Site, defended the harbor of San Juan and good fortune was on the side of the Spanish. A miscalculation by Drake, together with the bravery of the defenders of El Morro led to a totally unexpected defeat for the English. Drake sailed on with his injured fleet to attack the port of Panamá in early January 1596, but was, once again, defeated. A couple weeks later, Sir Francis Drake died aboard ship of dysentery on January 28, 1596, and was buried at sea near Portobelo on the Caribbean coast of Panamá. |

Last updated: December 30, 2022