Last updated: March 12, 2025

Person

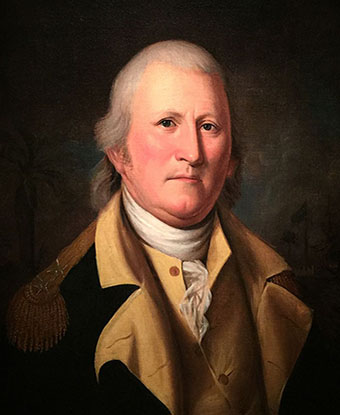

William Moultrie

National Portrait Gallery

William Moultrie, South Carolina’s famous Revolutionary War hero, successfully defended Charleston during the Battle of Sullivan’s Island on June 28, 1776, in which he dealt the Royal Navy a crushing defeat. After the war, he returned to politics, serving two terms as governor.

Born in Charleston in 1730, William Moultrie was the son of Dr. John Moultrie and Lucretia Cooper Moultrie. At age 19, Moultrie married Elizabeth Damarius de St. Julien, and the couple had three children, one dying in infancy. In 1752, he was elected to the Commons House of Assembly, beginning a political career that lasted until 1794. By 1761, he owned a rice plantation and about 200 enslaved people. The same year, during the Cherokee War, Moultrie was commissioned a captain in the South Carolina militia. By 1774, he held the rank of colonel. Moultrie’s military experience and social status resulted in his prominent role in South Carolina during the Revolutionary War.

As relations with Great Britain worsened in the 1770s, the American colonies prepared for war and increasingly debated on the merits of independence. As South Carolina’s capital, Charleston became a center for revolutionary activity. In 1775, a Provincial Congress was formed and elected Moultrie as a member.

In June he was made colonel of the 2nd South Carolina Regiment. At the time, there was no official American or South Carolina flag, so Moultrie designed one for his command. The dark blue flag resembled the color of his men’s regimental coats and also featured a white crescent in the top left corner. Moultrie proudly wrote in his memoirs that his flag became a symbol of defiance of the British and the “first American flag...displayed in South Carolina.”

Sullivan’s Island commanded the approach to Charleston Harbor. From the island, patriots could deny British warships entrance. In December 1775, a company of Moultrie’s regiment was ordered to secure the island and prevent British troops, on two ships blockading the harbor, from landing. Addtionally, Moultrie commanded troops who raided camps on Sullivan's Island where runaway enslaved people had fled to seek freedom and join the British war effort. Many were killed in the fighting, and the others were returned to slavery. When the colonel assumed command of the island in March 1776, he found a “great number of mechanics and negro laborers” at work using thousands of palmetto logs and sand to build a fort sufficient for 1,000 men.

On the morning of June 28, 1776 nine British warships, commanded by Commodore Sir Peter Parker, attacked the incomplete fort on Sullivan’s Island. Armed with only 31 cannons, Moultrie’s command faced over 270 British cannons. The fort’s palmetto log and sand walls absorbed much of the British fire and suffered little damage. After over nine hours of combat, the British fleet was defeated. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island ended in a decisive patriot victory.

Several days later, South Carolina’s legislature honored Col. Moultrie’s defense of Charleston by officially renaming the fortification Fort Moultrie. In September 1776, Moultrie was promoted to brigadier general in the Continental Army. Moultrie enjoyed further success later in the war. In February 1779, at the Battle of Beaufort, Moultrie commanded a largely militia force and defeated the British, boosting patriot morale after the British capture of Savannah, Georgia. In the spring of 1779, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, the commander of the Continental Army's Southern Department, took the bulk of the southern army to threaten Augusta, Georgia. Seizing the initiative, the British advanced on Charleston from Savannah. Moultrie led a skillful tactical withdrawal from Black Swamp where Lincoln had left him with a small force. This small force garrisoned Charleston and held off a brief British siege before Lincoln's force returned.

Another successful defense of Charleston proved impossible when he served under Lincoln in the siege of Charleston the following year. After Charleston surrendered in May 1780, Moultrie was imprisoned at Haddrell’s Point and at Snee Farm. He did admirable service in representing his fellow Continental Army POWs and advocating against their harsh treatment to the British commandant of Charleston, Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour. Moultrie was later sent to Philadelphia, where he was exchanged in early 1782.

After independence was secured, Moultrie returned to the General Assembly in 1783. Two years later, he was elected governor. He served until 1787, during which time his legislative and military experience proved valuable in dealing with various topics: reorganization of the state militia, management of the loyalist diaspora, creation of a county court system, and relocation of the capital from Charleston to Columbia.

Moultrie served a second term as governor, starting in 1792. Because of the increasing political tension between Federalists and Antifederalists, it proved to be a difficult term. Moultrie drew harsh criticism for his public support of the French Revolution and its representative in Charleston, Citizen Genet, who had attempted to license privateers and recruit volunteers to retake Louisiana from Spain for France. Criticism from President Washington’s administration ended Genet’s work and forced Moultrie to issue a proclamation forbidding South Carolinians from enlisting in any French military expeditions.

Leaving office in 1794, Moultrie retired from politics but stayed active with various organizations: the South Carolina Society, St. Andrew’s Society, South Carolina Jockey Club, and president of the state Society of the Cincinnati from its creation in 1783 until his death. In 1802, Moultrie published his Memoirs of the American Revolution, an incredibly valuable resource for students of the war. He died in Charleston on September 27, 1805.

Sources

Bragg, C.L. Crescent Moon over Carolina: William Moultrie & American Liberty. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2013.

Moultrie, William. Memoirs of the American Revolution. New York: David Longworth, 1802.