Last updated: September 13, 2025

Article

Siege of Charleston 1780

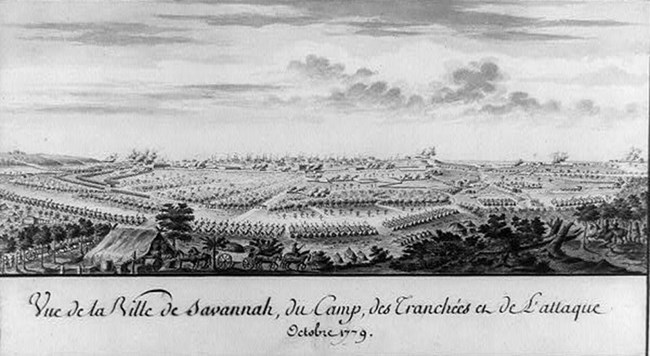

Wikimedia Commons

British Southern Campaign

Free from British attack since their victory at Sullivan's Island on June 28, 1776, southern states sent their soldiers and financial assistance to the northern theater. The last major battle in the northern theater, however, was fought in 1778 at Monmouth in central New Jersey. In 1779, the war in the north was largely at a stalemate. The British were bottled in New York, defending outposts on the Hudson River against patriot attacks, while the Americans waged a large campaign against the Six Nations in New York.

Lord George Germain, the Secretary of State for America, trusted reports of high loyalist sentiment in the southern colonies, which were exaggerated by former royal governors and notable loyalists. American loyalist support never matched expectations, frustrating British efforts in the region. Germain executed the decisions of the ministry and communicated the wishes of the king and his cabinet to the military commanders in America. Economic considerations and relative proximity to British possessions in the Caribbean also influenced the British shift in strategy. The wealth of the southern colonies helped finance the American war effort. Additionally, with the entrance of France into the war as an American ally in 1778, the British sought to protect their sugar islands in the Caribbean and conquer French possessions there.On December 29, 1778, a British expeditionary force of 3,500 men from New York, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell, captured Savannah, Georgia. They were later joined by a British force marching overland from British East Florida, commanded by Brigadier General Augustine Prevost. Prevost sent Campbell with 1,000 men to capture Augusta, Georgia on the Savannah River and to recruit local loyalists.

Library of Congress

By April, Lincoln had been reinforced by South Carolina militia. He decided to move toward Augusta. Leaving 1,000 men under the command of Moultrie at Purrysburg to monitor Prevost, he began the march north on April 23. Prevost, in response, led 2,500 men from Savannah toward Purrysburg on April 29. Moultrie fell back toward Charleston rather than engaging, and Prevost was within 10 miles of Charleston on May 10 before he faced American armed resistance. Two days later, he intercepted a message indicating that Lincoln, alerted to Prevost's advance, was hurrying back from Augusta to assist in the defense of Charleston. Prevost retreated to the islands southwest of Charleston, leaving an entrenched force at Stono Ferry to cover his retreat. Lincoln decided to attack the British rear guard. Lincoln's force, largely composed of untested militia, was repulsed by the British on June 20 in the Battle of Stono Ferry. The British, abandoning their attack against Charleston, marched south towards Beaufort.

The successful defense of Savannah against a Franco-American expedition in the fall of 1779 brought renewed British attention to expanding their southern campaign. Two months later, on December 26, 1779 a British fleet set sail for Charleston and conquest. The British fleet numbered over 100 ships, including 90 transports and five ships of the line, one fifty gun ship, two forty-four gun ships, four frigates, and two sloops. Over 8,700 men embarked to attack Charleston, which rivaled the size of General John Burgoyne's 1777 force, and included British infantry, cavalry, and artillery, Hessian infantry, and provincial loyalist units. British troops included two battalions of light infantry, two battalions of grenadiers as well as four Hessian grenadier battalions and 250 jaegers, armed with rifles. Jaegers were responsible for scouting, picket duty, and skirmishing. A detachment of the Royal Artillery proved invaluable for the siege of Charleston.

To help defend Charleston, General George Washington ordered his Virginia Continentals south just as they had begun construction of their winter quarters near Morristown, New Jersey. They marched 500 miles in twenty-eight days, hurrying to aid the Southern Department.

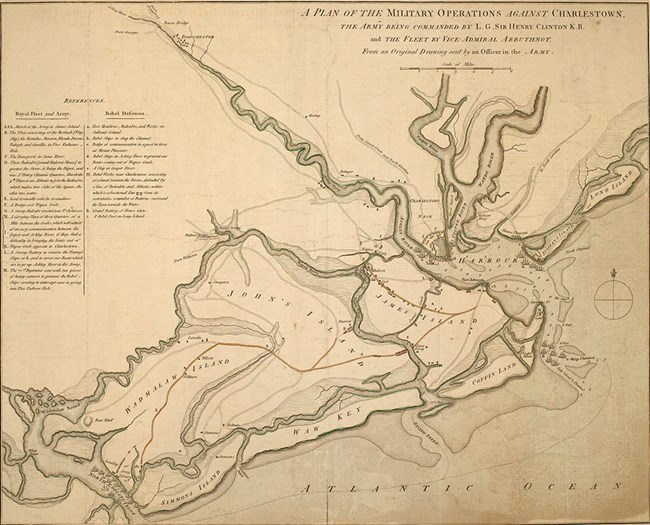

Royal Collection Trust

Severe winter weather, the beginning of the coldest winter on record, lengthened the voyage and damaged the British fleet. Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander-in-chief of forces in America and the army commander of the campaign, grew frustrated with the length and hardships of the voyage, blaming Admiral Marriot Arbuthnot, the naval commander of the operation. Captain Johann Hinrichs of the jaegers chronicled that of thirty-six days at sea on the Apollo, fifteen of them were stormy. He noted sourly that the men could not enjoy "a moment of sleep because of the fearful rolling and noise" in the cabins of the ships.1 Normally the voyage from New York to Savannah took ten days, but the severe weather delayed and ravaged the fleet, taking them five weeks to reach the Georgia coast. British forces were to land on one of the sea islands south of Charleston. They would then move troops overland via the sea islands and then up the Ashley River, using the navy's smaller transport vessels. Once across the Ashley River, the British and Hessians would lay siege lines across the peninsula and shut in the town from the north.

Light infantry and grenadiers landed first on Simmons Island (today Seabrook Island), an isolated location distant enough from Charleston and the Continental Army to ensure a secure landing, on February 11-12. The distance, however, featured difficult terrain. Hinrichs complained that the day's march to headquarters took them "through a wilderness of deep sand, marshland, and impenetrable woods where human feet had never trod! What a land to wage war in!"2 From Johns Island, the British and Hessians crossed over the Stono River unopposed by the defenders of Charleston to James Island. By March 1, the British controlled James Island. Two days later, they crossed the Wappoo Cut and established themselves on the mainland. They crossed over the Ashley River at Drayton Hall onto the Charleston Neck on March 29.

Brown University

Siege of Charleston

On April 1, the British began their first siege parallel. The American fortifications stretched across Charleston Neck between the two rivers; the focal point was a tabby hornwork, a remnant of which remains in Marion Square. On April 8, the Royal Navy forced their way past Fort Moultrie, giving them control of Charleston Harbor. On April 8, the promised reinforcements of 750 Virginia Continentals under Brigadier General William Woodford arrived, cheering the Charlestonians and defenders of the garrison.Two day later Clinton and Arbuthnot summoned the American garrison, offering them the chance to surrender; General Lincoln responded that "duty and inclination" dictated that he defend the city "to the last extremity." The British commenced their bombardment of Charleston on April 13, and the two sides exchanged artillery and small arms fire from then until the siege's conclusion. The completion of a second parallel on April 17 brought British guns even closer to Charleston.

Informed by his officers that their fortifications were too weak to hold and provisions were running low, Lincoln called a council of war to discuss their options. Some officers, including Brigadier Generals Lachlan McIntosh and William Moultrie, favored evacuation of the army, but civilian officials, led by Lieutenant Governor Christopher Gadsden and Thomas Ferguson of the Privy Council, strongly discouraged the attempt. Ferguson even threatened to turn the civilians of Charleston against the army. Ultimately, Lincoln and his officers offered terms of capitulation that would give the British the city and allow the American army to retreat to the backcountry. Clinton and Arbuthnot rejected these proposals.

The British, meanwhile, steadily surrounded and isolated the American army in Charleston. On April 14 a force under Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton smashed the American cavalry under Brigadier General Isaac Huger at Moncks Corner, giving the British access to the area east of the Cooper River. Clinton sent Charles Lord Cornwallis and a detachment of troops over the Cooper to block American escape attempts. When the Americans evacuated Lempriere's Point (Hobcaw) and the Royal Navy captured Fort Moultrie, the British effectively enveloped Charleston. The completion of their third parallel allowed them to hammer the city from even closer distance.

The surrender terms imposed by the British were harsh. Lincoln's army was refused the honors of war. Lincoln and his senior officers awaited exchange in relatively comfortable quarters while the soldiers and junior officers were confined in prison ships. Many of the 2,500 Continentals who surrendered did not survive their imprisonment. The British captured over 300 cannons and about 6,000 muskets, along with vast stores of gunpowder. Overall, the casualties in the siege were relatively low, with fewer than 300 killed and wounded on either side; an accidental explosion in a magazine after the surrender killed twice as many men as died in the actual siege.

The greatest British victory of the war elevated Sir Henry Clinton to the peak of his military career. Before Clinton left South Carolina for New York, he left the theater commander, Cornwallis, with specific instructions to safeguard Charleston and South Carolina. Clinton also committed a grave error on June 3, 1780, issuing a proclamation declaring that all men who had been given parole were released from that state and required to swear allegiance to the crown, and expected to serve when ordered by His Majesty's government. This mistake sent more Americans into the patriot ranks and left Cornwallis with a difficult task to impose British control throughout South Carolina.

Footnotes

1. Bernhard A. Uhlendorf, The Siege of Charleston: With an Account of the Province of South Carolina, Diaries and Letters of Hessian Officers (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1938), 119.2. Ibid, 183.

Sources

Borick, Carl. A Gallant Defense: The Siege of Charleston, 1780. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2003.O'Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson. The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution and the Fate of the Empire. United States: Yale University Press, 2013.

Uhlendorf, Bernhard A. The Siege of Charleston: With an Account of the Province of South Carolina, Diaries and Letters of Hessian Officers. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1938.