Last updated: January 12, 2026

Person

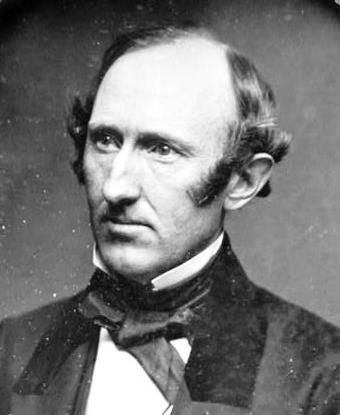

Wendell Phillips

Library of Congress

During a eulogy for Wendell Phillips given at Tremont Temple on April 9, 1884 the Honorable George L. Ruffin stated "No other class of people can with great propriety meet to pay tribute to the memory of Wendell Phillips than the descendants and representatives of those for whose freedom he labored so long."1 Phillips dedicated his life and career to the causes of abolition and social reform.

Born on November 28, 1811, Wendell Phillips came from a family with deep New England ties. Phillips enrolled at Harvard Law School in 1831, passed the Massachusetts Bar, and opened his own law practice in Boston in 1834.2

On October 21, 1835, Phillips witnessed from the window of his Court Street office a mob search for the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. The mob took to the streets, angered by Garrison's abolitionist newspaper The Liberator and by the abolition meeting scheduled for later in the day at the headquarters of the Female Anti-Slavery Society on Washington Street.3 Many accounts cite this October day as the spark for Phillips' work as an abolitionist.

Nicknamed abolition's "golden trumpet," one of Phillips' early successes as an orator came during a meeting at Faneuil Hall when he denounced the 1837 murder of the abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy by a mob. Enraged by a speech given by Massachusetts Attorney General James T. Austin, Phillips condemned Austin's comparison of the murderous mob to Boston's revolutionary patriots. Concluding his speech, Phillips stated,

Faneuil Hall has the right, it is her duty to strike the key note for these United States. I am glad for one reason, that remarks such as those to which I have alluded, have been uttered here. The passage of these resolutions in spite of them, will show more clearly, more decisively, the deep indignation with which Boston regards this outrage.4

Soon after this event Phillips gave up his promising law practice and "gave himself, heart and soul, to the cause of abolition."5

Wendell Phillips served with other prominent abolitionists, such as Lewis Hayden, on the Boston Vigilance Committee executive committee.6 Phillips actively advocated for disunion from the slave-holding South and in 1854 was indicted for his role in the attempt to aide freedom seeker Anthony Burns.7

During the Civil War, Phillips staunchly advocated for the raising of Black regiments, including the 54th Massachusetts. He gave many speeches in support of these regiments and encouraging men to join in the war effort.8

After the abolition of slavery, Phillips continued to be a staunch supporter of social reform and civil rights. Phillips fought for women's suffrage and at the 1873 New England Women's Tea Party, he notably stated "…Women shall have her share at the ballot-box. The founders of this great government are represented by them. They are the lineal descendants and representatives of 1776."9 In addition to his work for women's suffrage, Phillips also spoke in favor of equal rights for Native Americans, arguing that the fifteenth amendment granted them citizenship.10 In 1870, Phillips unsuccessfully ran for Governor of Massachusetts.11

On February 2, 1884 Wendell Phillips died after suffering from heart disease.12 Following his death, Reverend Joseph Cook wrote of Phillips in a Boston Globe article, "What cares he for our praise or blame? Fifty years hence men will not ask what Boston thought of Wendell Phillips but what did Phillips think of Boston."13

Footnotes

- Archibald H. Grimke, “A Eulogy on Wendell Phillips: together with the proceedings incident thereto, letters, etc.” (Boston: Press of Rockwell and Churchill, 1884), 5.

- According to Boston city directories, from 1845 to 1870 Phillips resided at 26 Essex Street and from 1872 to 1875 he is listed at 50 Essex Street. National Park Service maps place Wendell Phillips at 26 Essex Street. Directories also indicate that Phillips’ law office was located at 11 Court Street.

- James Brewer Stewart, Wendell Phillips: Liberty’s Hero (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986), 42.

- “Speech of Mr. Phillips,” The Liberator, December 15, 1837.

- Stewart, Wendell Phillips: Liberty’s Hero, 63.

- Austin Bearse, Reminiscences of Fugitive Slave Law Days in Boston (Boston: Warren Richardson, 1880), 6.

- Albert J. Von Frank, The Trials of Anthony Burns: Freedom and Slavery in Emerson’s Boston (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 331.

- Louis Emilio, History of the Fifty-fourth regiment of Massachusetts volunteer infantry, 1863-1865 (Boston: Boston Book Company, 1891) 21.

- New England Woman's Tea Party," The Woman's Journal 4, no. 51 (December 20, 1873) 1.

- James Brewer Stewart, Wendell Phillips: Liberty’s Hero, 31.

- Irving H. Bartlett, Wendell Phillips: Brahmin Radical (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 351-355.

- “Wendell Phillips: Death of an Apostle,” The Boston Globe, February 3, 1884.

- “Joseph Cook’s Tribute: Three Periods in Wendell Phillip’s Life,” The Boston Globe, February 5, 1884.