Last updated: January 14, 2026

Article

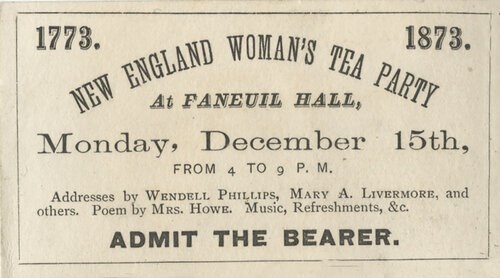

New England Woman's Tea Party

Courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum.

The women of New England who believe that “TAXATION WITHOUT REPRESENTATION IS TYRANNY,” and that our forefathers were justified in resisting despotic power by throwing the tea into Boston Harbor, hereby invite the men and women of New England to unite with them in celebrating the One Hundredth Anniversary of that event, in Faneuil Hall, on MONDAY AFTERNOON AND EVENING, DEC. 15, from 4 to 9 P.M.[1]

Three thousand women and men crowded into Faneuil Hall in response to that call from the New England Woman Suffrage Association. They came for a multitude of reasons. They came to find hope against the discouragement engendered by the movement’s recent failures to gain the vote, and by its increasingly angry splits. They came to contradict the statement overheard by William Lloyd Garrison that "the Woman Suffrage movement was retrograding and will soon disappear." They came also to make a public statement of the principles and philosophy of the movement and to issue a call for action.

Two banners decorated the Hall that day. One over the stage declared, "Taxation without representation is tyranny." The other on the right hand balcony professed, "Governments derive their just power from the consent of the governed." Lucy Stone spoke for many when she called to "make it keenly felt, and clearly understood, here and now, that the taxation of women without representation, is as great an injustice as was that done to men in the olden time."

The argument was clear: the Suffrage movement was claiming to be, in the words of Wendell Phillips, the "lineal descendants and representatives of 1776." Phillips argued that truly representing the founders required carrying their principles further, for the men of 1776 had fallen short of their own ideals. The men of 1776 had "shut their eyes on one side to women, and on the other side to the negro, and narrowed the great Republic of the last seventy years to a white male Republic."

Speaker after speaker declared that the women of this "white male republic" were oppressed by this failure. They were taxed without representation, denied guardianship of their children, denied the right to make a will without their husband’s consent, paid less than men for the same work, ignored in their state of poverty, and denied their just position as man’s equal. In this situation, Mary Livermore argued, women must "get to the underlying cause and obstacle of our hindrance… it is because we have no political rights which these Congressmen feel bound to respect." Livermore and others agreed that women could not simply rely on male kindness to correct these wrongs. Women would not gain justice until they gained the power of suffrage in and for themselves. When we have the vote, Livermore said, we will compel governments to address our needs. Legislators "would know how short would be the tenure of their office if they did not grant your petition."

ca. 1876-1895, Boston Public Library

The meeting also sent out a call for action to achieve the vote. Lucy Stone called upon women to treat the 1876 celebration of the American centennial as an occasion for protest, holding banners that read,

We are taxed, and we have no representation. We are governed without our consent. We are fined, imprisoned, and hung with no jury trial, by our peers. We have no legal right to our children, nor power to sell our land, nor will our money.

James Freeman Clarke pushed even farther. The original Tea Party he said was "breaking the law … plainly a riot… But it was breaking the lower law, and obedience to the higher law." It should be celebrated "as a declaration of faith in the spirit of justice, of law, of duty—as always being above the letter." Stephen S. Foster gave one example of what that celebration could mean when he declared, "I have paid the last cent of taxes voluntarily that I shall ever pay to a government which puts its foot on the necks of my wife and daughter."

In the coming years, women responded to this call with marches and petitions, with more tax resistance, by publicly and illegally casting ballots in elections, by chaining themselves to the White House fence, by hunger strikes and other radical acts of protest until they won their victory.

So what did this Woman’s Tea Party actually accomplish? On one level, very little. Women would not win the vote until 1920. Few if any of the people who came to Faneuil Hall in 1873 would even live to see the 19th Amendment ratified. But the hope expressed, the principles declared, and the call to action led and sustained the movement through increasingly violent opposition to its final success. That enduring hope, those principles, and the action resulting from them were honored in the speech Maud Wood Park gave in that same Faneuil Hall to celebrate the victory:

For the women it [the vote] means completed citizenship in the United States; for the United States it means making into living fact that ideal which has been implied in our Government since the beginning… A great price has been paid for our suffrage, a long, weary trail has brought us to this day, and we owe it to the women who have made today possible to be worth being enfranchised.[2]