Last updated: January 16, 2023

Person

Benjamin Roberts

Boston Public Library

A Black printer and writer for Boston area newspapers, Benjamin Franklin Roberts fought for equal access to education for his children. Though slavery had been abolished in Massachusetts in the late 1700s, segregation still influenced every part of public life, including education. By the time Benjamin Roberts’ children began attending school, Boston had a two-tiered system: multiple neighborhood public schools for its White students and one public school for its Black students.1

The Roberts family valued community activism, a tradition going back to Roberts’ grandfather, James Easton. In 1776, Easton enlisted in the Continental Army and helped establish the breastwork on Dorchester Heights above the town of Boston. Not much is known about Easton’s service, but he served until 1780 and later moved to Brockton, Massachusetts. As he and his wife, Sarah, raised their family, they instilled a sense of duty into their children. Beginning in 1800, the Eastons staged protests against segregation in their church. The family protested at least six times against discrimination in various churches throughout Massachusetts.2

Roberts continued that family tradition by advocating for equal education for two of his children: Sarah and Benjamin Jr. After entering his daughter into the Otis School, a local school for White children, in 1848, Roberts decided to enroll his eldest son into the same school. This plan ultimately failed and resulted in both children being denied access to their right to join an integrated classroom.3 Roberts hired two lawyers, Robert Morris and Charles Sumner, and sued on behalf of his daughter Sarah in the case Roberts v. City of Boston. Though Sumner and Morris argued against this segregation to the best of their ability, the courts ruled against them in 1850.

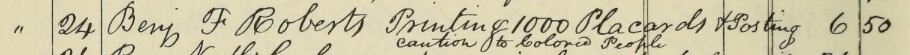

Throughout his life, Roberts used his talents as a writer and printer to advocate for his community. Following the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, he printed the Caution Colored People of Boston broadside warning of slave catchers in the city.4 He also supported seven petitions between 1843 and 1873 advocating for interracial marriage, for equal education, against capital punishment, and for the removal of the word "color" from the statute books.

In his April 10, 1850 petition on equal education, Roberts asserted his Boston roots and ancestry as the "grandson of one of the Soldiers of the Revolution." He condemned the injustice of "having two sons and three daughters who are all banished from the schools nearest their residence on account of not wearing a skin quite as pale as the children of their neighbors and doomed to take the benefit of an exclusive school or none…"5

By the time Massachusetts integrated public schools in 1855, the Roberts family had moved to Chelsea. Benjamin Roberts brought his printing press with him and continued to print books and pamphlets for local Black authors and causes. On September 6, 1881, Benjamin Roberts died of epilepsy.6 Today, he is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.7

Footnotes

- While there were a variety of schools for Black children to attend in the city of Boston, the Abiel Smith School was the first public school, established in 1835. For a background on Boston schools available prior to 1835, please refer to pages 9-11 in The Smith School House Historic Structure Report.

- George R. Price and James Brewer Stewart, "The Roberts Case, the Easton Family, & the Dynamics of the Abolitionist Movement in Massachusetts, 1776-1870." Massachusetts Historical Review 4 (2002): 89-115. Accessed November 13, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25081172.

- Digital Archive of Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions, Massachusetts Archives, “House Unpassed Legislation 1851, Docket 3139, SC1/Series 230, Petition of Benjamin F. Roberts,” Harvard Dataverse, February 5, 2017. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi%3A10.7910%2FDVN%2FZEDHH.

- Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston, Dr. Irving H. Bartlett collection, 1830-1880, W. B. Nickerson Cape Cod History Archives, 18. https://archive.org/details/drirvinghbartlet19bart/page/18/mode/2up.

- Digital Archive of Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions, Massachusetts Archives, “House Unpassed Legislation 1850, Docket 2556, SC1/Series 230, Petition of Benjamin F. Roberts.” Harvard Dataverse, February 5, 2017. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi%3A10.7910%2FDVN%2FMBSYO.

- "Massachusetts Deaths, 1841-1915, 1921-1924," entry for Benjamin F. Roberts, 06 Sep 1881; citing Boston, Massachusetts, v. 330 p. 216, State Archives, Boston; FHL microfilm 960, 221.

- Friends of Mount Auburn, “African American Heritage Trail – Benjamin Franklin Roberts: Mount Auburn Cemetery.” Mount Auburn Cemetery African American Heritage Trail Benjamin Franklin Roberts Comments, February 1, 2013. https://mountauburn.org/aaht-roberts/.