Last updated: May 29, 2024

Article

The Sarah Roberts Case

The following article was originally published on Smith Court Stories, a digital classroom for teachers and students. Please visit the digital classroom for more articles about Education at Smith Court.

Within ten years of the Abiel Smith School’s opening at 46 Belknap (now Joy) street, the school had fallen into disrepair. By 1846, the Smith School required significant improvements, for

The school rooms are too small, the paint is much defaced, and every part gives evidence of the most shameful negligence and abuse. There are no recitation rooms, or proper places for overclothes, caps, bonnets, etc. The yards, for each division, are but about fifteen feet square, and only accessible through a dark, damp cellar.[1]

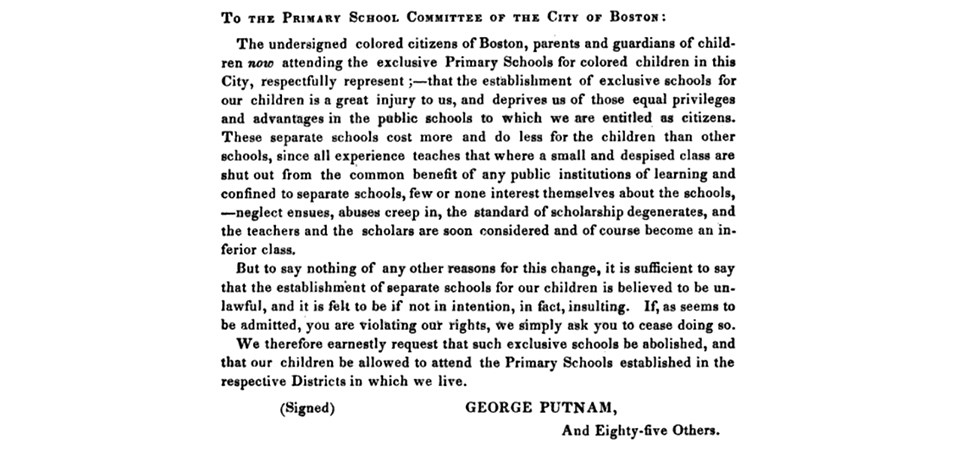

While the African American community had first supported educating their children within a Black school, they soon saw the significant discrepancies due to segregated education. In response to this apparent inequality, community members launched petition drives to urge the Boston Primary School Committee to desegregate local primary and grammar schools. Petitions launched in 1844, 1845, and 1846 all failed to achieve their goal.[2] The 1846 petition and its response demonstrate the contention between the Black community and the Primary School Committee. The petitioners wrote

the establishment of exclusive schools for our children is a great injury to us, and deprives us of those equal privileges and advantages in the public schools to which we are entitled as citizens. These separate schools cost more and do less for the children than other schools…[3]

They went on to decry that school segregation "is believed to be unlawful," and urged the committee "that such exclusive schools be abolished."[4]

Report to the Primary School Committee

In response, the Majority opinion of the Committee refused to submit to the petitioners' demands, using racist language to confirm the need for separate schooling of White and Black schoolchildren. They argued that Black schoolchildren’s "peculiar physical, mental, and moral structure, requires an educational treatment, different, in some respects, from that of white children."[5]

As if tempting fate, the Boston Primary School Committee wrote that the petitioners could take their case to court if they found the Committee's ruling unjust: "The law is open, and [the petitioners] can procure redress at the hands of the civil Courts."[6] The Committee did not have to wait long before one of those petitioners, Benjamin Roberts, took that challenge.

Sarah Roberts v. City of Boston

In 1847, local printer Benjamin Roberts applied to the Boston Primary School Committee for his daughter, five year-old Sarah Roberts, to attend a school located close to their house on Andover Street, a school that educated White children. The Committee denied his request four times on the basis that Sarah could attend the local school for Black children instead. Frustrated by the fact that Sarah had to pass five schools for White children on her walk to the Abiel Smith School, the closest school for Black children, Roberts entered Sarah into the school nearest her house in 1848. After the school ejected her, Benjamin Roberts filed a suit against the city under the following 1845 statute:[7]

Any child, unlawfully excluded from public school instruction, in this Commonwealth, shall recover damages therefor, in an action on the case, to be brought in the name of said child, by his guardian or next friend, in any court of competent jurisdiction to try the same, against the city or town by which such public school instruction is supported.[8]

Courtesy of Social Law Library, Boston, Massachusetts

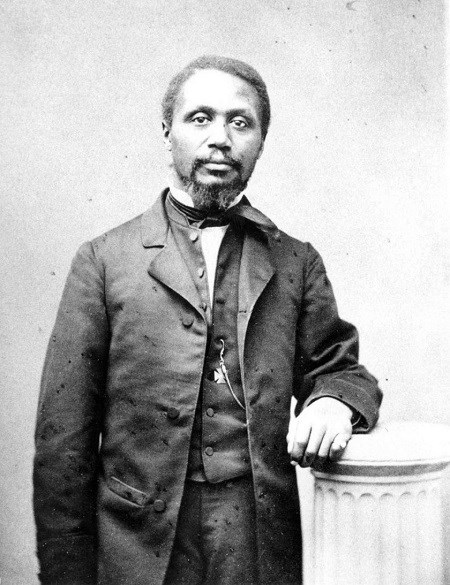

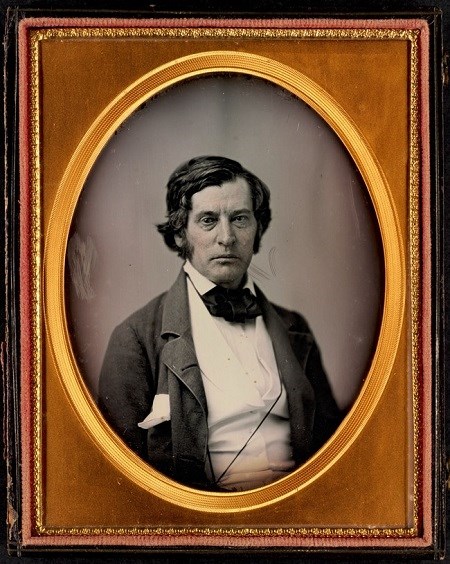

For his case, Benjamin Roberts turned to attorney Robert Morris, one of the first African American men to pass the bar in Massachusetts. Historians Paul and Stephen Kendrick note that Morris "framed [the case's] initial arguments," specifically applying the statute to Sarah Roberts' case.[9] Morris then sought a young Charles Sumner, future abolitionist Massachusetts senator, as his co-counsel to help apply Sarah's case to the greater need for equal schools.[10] Morris and Sumner represented Benjamin and Sarah Roberts when the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court heard the case on November 1, 1849.[11] At this hearing, Sumner gave a fiery speech that spoke to the injustice of segregated schooling. He began by reminding the judges that the Massachusetts constitution explicitly states, "all men, without distinction of color or race, are equal before the law."[12] Sumner then applied this understanding to the school system:

The legislation of Massachusetts has made no discrimination of color or race in the establishment of the public schools. The laws establishing public schools speak of “schools for the instruction of children” generally, and “for the benefit of all the inhabitants of the town,” not specifying any particular class, color or race.[13]

Considering this, Sumner argued school segregation on the basis of race "is a violation of equality."[14] He concluded that the Boston Primary School Committee had no power to determine the school a child may attend on the basis of race.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library

Sumner ended his argument by articulating the danger of segregated education:

The separation of the schools, so far from being for the benefit of both races, is an injury to both. It tends to create a feeling of degradation in the blacks, and of prejudice and uncharitableness in the whites.[15]

Despite Robert Morris and Charles Sumner's best efforts, Judge Lemuel Shaw of the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled on the side of the Boston Primary School Committee in 1850.[16] While Judge Shaw recognized Sumner's use of the Massachusetts Constitution in proving equality before the law, he believed this equality varied depending on the person. Shaw declared:

But, when this great principle comes to be applied to the actual and various condition of persons in society, it will not warrant the assertion, that men and women are legally clothed with the same civil and political powers, and that children and adults are legally to have the same functions and be subject to the same treatment...What those rights are, to which individuals are entitled...must depend on laws adapted to their respective relations and conditions.[17]

Judge Shaw concluded that the Boston Primary School Committee had the power to designate schools for children to attend, and he even supported the notion of school segregation:

The committee… have come to the conclusion, that the good of both classes of school will be best promoted, by maintaining the separate primary schools for colored and for white children, and we can perceive no ground to doubt, that this is the honest result of their experience and judgement.[18]

In doing so, Judge Shaw provided precedent to the "separate, but equal" argument seen in later legal cases, most notably Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, which helped solidify Jim Crow segregation throughout the country.[19]

This ruling posed a significant setback for the equal schools movement in Boston. Despite the new obstacle put forth by the judicial system, many African Americans and their allies continued to work for school desegregation. Due to the work of many dedicated activists, including William C. Nell the Massachusetts legislature finally outlawed public school segregation in 1855 in a significant and widely celebrated win for the equal schools movement.

Footnotes

[1] "City Document No. 28: Report of the Annual Visiting committees of the Public Schools of the City of Boston" (Boston, 1846), p. 151, as printed in Leonard W. Levy and Harlan B. Philips, "The Roberts Case: Source of the 'Separate but Equal' Doctrine," The American Historical Review 56, no. 3 (1951): 511.

[2] "Report to the Primary School Committee, June 15, 1846, on the Petition of Sundry Colored Persons, for the Abolition of the Schools for Colored Children," (Boston, June 15, 1846).

[3] "Report to the Primary School Committee," 2.

[4] "Report to the Primary School Committee," 2.

[5] "Report to the Primary School Committee," 29.

[6] "Report to the Primary School Committee," 4.

[7] James Oliver Horton and Lois Horton, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1999), 78-79; Levy and Philips, "The Roberts Case: Source of the 'Separate but Equal' Doctrine," 510-518; Douglas J. Ficker, "From Roberts to Plessy: Educational Segregation and the "Separate but Equal" Doctrine." The Journal of Negro History 84, no. 4 (1999): 301-14; Sarah C. Roberts vs. The City of Boston 59 Mass. 198, 5 Cush. 198 (1849).

[8] "An Act Concerning Public Schools," in Acts and Resolves Passed by the General Court (Session Laws, Boston, 1845).

[9] Paul Kendrick and Stephen Kendrick, Sarah’s Long Walk: The Free Blacks of Boston and How Their Struggle for Equality Changed America (Boston: Beacon Press, 2004) 116.

[10] Horton and Horton, Black Bostonians, 78-79; Kendrick and Kendrick, Sarah’s Long Walk.

[11] Horton and Horton, 78-79.

[12] Sarah C. Roberts vs. The City of Boston 59 Mass. 198, 5 Cush. 198 (1849).

[13] Sarah C. Roberts vs. The City of Boston 59 Mass. 198, 5 Cush. 198 (1849).

[14] Sarah C. Roberts vs. The City of Boston 59 Mass. 198, 5 Cush. 198 (1849).

[15] Sarah C. Roberts vs. The City of Boston 59 Mass. 198, 5 Cush. 198 (1849).

[16] Court case records do not contain the arguments of Peleg W. Chandler, the City Solicitor. Donald M Jacobs, "The Nineteenth Century Struggle Over Segregated Education in the Boston Schools." The Journal of Negro Education 39, no. 1 (1970): 76-85.

[17] Sarah C. Roberts vs. The City of Boston 59 Mass. 198, 5 Cush. 198 (1849).

[18] Sarah C. Roberts vs. The City of Boston 59 Mass. 198, 5 Cush. 198 (1849).

[19] Ficker, "From Roberts to Plessy," 301-14.

Tags

- boston african american national historic site

- african americans

- boston

- education

- school desegregation

- abiel smith school

- smith court

- beacon hill

- african american history

- african american history and culture

- education history

- women and education

- civil rights

- massachusetts

- shaping the political landscape

- desegregation in the cradle of liberty

- unfinished 250