| Marines in World War II |

|

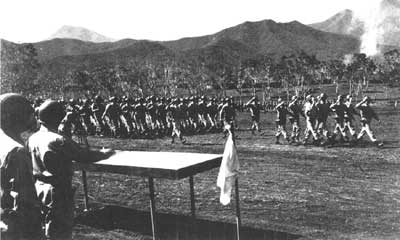

SILK CHUTES AND HARD FIGHTING: US. Marine Corps Parachute Units in World War II by Lieutenant Colonel Jon T. Hoffman (USMCR) Recuperation and Reevaluation The 1st Parachute Battalion arrived in New Caledonia and went into a "dreadful" transient camp. For the next few weeks the area headquarters assigned the tired, sick men of the orphaned unit to unload ships and work on construction projects. Luckily Lieutenant Colonel Williams returned to duty after recovering from his wound and took immediate steps to rectify the situation. The battalion's last labor project was building its own permanent quarters, named Camp Kiser after Second Lieutenant Walter W. Kiser, killed at Gavutu. The site was picturesque; a grassy, undulating plain rising into low hills and overlooking the Tontouta River. Wooden structures housed the parachute loft and messhalls, but for the most part the officers and men lived and worked in tents. The two dozen transport planes of VMJ-152 and VMJ-253 occupied a nearby air field. The parachutists made a few conditioning hikes while they built their camp and began serious training in November. The first order of business was reintroducing themselves to their primary specialty, since none of them had touched a parachute in many months. They practiced packing and jumping and graduated to tactical training emphasizing patrolling and jungle warfare. The 1st Battalion received company on 11 January 1943, when the 2d Battalion arrived at Tontouta and went into bivouac at Camp Kiser. The West Coast parachute outfit had continued to build itself up while its East Coast counterpart sailed with the 1st Marine Division and fought at Guadalcanal. During the summer of 1942, the 2d Battalion had found enough aircraft in busy southern California to make mass jumps with up to 14 planes. (Though "mass" is a relative term here; an entire battalion required about 50 R3D-2s to jump at once.) The battalion also benefitted from its additional time in the States, as it received Johnson rifles and light machine guns in place of the reviled Reisings. However, the manpower pipeline was still slow, as Company C did not come into being until 3 September 1942 (18 months after the first parachutists reported to San Diego for duty). The battalion sailed from San Diego in October 1942, arrived at Wellington, New Zealand in November, and departed for New Caledonia on 6 January 1943.

As the 2d Battalion prepared to head overseas, it detached a cadre to form the 3d Parachute Battalion, which officially came into existence on 16 September 1942. Compared to its older counterparts, the 3d Battalion grew like a weed and reached full strength by the end of December. The battalion commander, Major Robert T. Vance, emphasized infantry tactics, demolition work, guerrilla warfare, and physical conditioning in addition to parachuting. At the beginning of 1943, the battalion simulated a parachute assault behind enemy lines in support of a practice amphibious landing by the 21st Marines on San Clemente Island. The fully trained outfit sailed from San Diego in March and joined the 1st and 2d Battalions at Camp Kiser before the end of the month. At the end of 1942, the Marine Corps had transferred the parachute battalions from their respective divisions and made them a I Marine Amphibious Corps asset. This recognized their special training and unique mission and theoretically allowed them to withdraw from the battlefield and rebuild while the divisions remained engaged in extended land combat. After the 3d Battalion arrived in New Caledonia in March 1943, I MAC took the next logical step and created the 1st Parachute Regiment on 1 April. This fulfilled Holland Smith's original call for a regimental-size unit and provided for unified control of the battalions in combat and in training. Lieutenant Colonel Williams became the first commanding officer of the new organization. Just when things appeared most promising for Marine parachuting, the Corps shifted into reverse gear. General Holcomb and planners at Headquarters had not shown much enthusiasm for the program since mid-1940 and apparently began to have strong second thoughts in the fall of 1942. In October, Brigadier General Keller E. Rockey, the director of Plans and Policies at HQMC, had queried I MAC about the "use of parachutists" in its geographic area. There is no record of a reply, but I MAC later sent Lieutenant Colonel Williams in a B-24 to make an aerial reconnaissance of New Georgia in the Central Solomons for a potential airborne operation. In early 1943, I MAC dragged its feet on planning for the Central Solomons mission and the Navy eventually turned to the Army's XIV Corps headquarters to command the June invasion of New Georgia. In March, the Navy decided that Vandegrift would take over I MAC in July, with Thomas as his chief of staff. They had suffered the loss of some of their best men to the parachute and raider programs during the difficult buildup of the 1st Marine Division and both believed that "the Marine Corps wasn't an outfit that needed these specialties." They made their thoughts on the subject known to Headquarters.

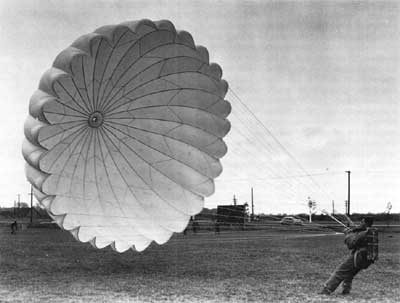

The chronic shortage of aircraft also continued to hobble the program. In the summer of 1943 the Corps had just seven transport squadrons, with only one more on the drawing boards. If the entire force had been concentrated in one place, it could only have carried about one and a half battalions. As it was, three squadrons were brand new and still in the States and another one operated out of Hawaii. There were only three in the South Pacific theater. These were fully engaged in logistics operations and were the sole asset available to make critical supply runs on short notice. As an example, the entire transport force in New Caledonia spent the middle of October 1942 ferrying aviation gas to Guadalcanal, 10 drums per plane, in the aftermath of the bombardment of Henderson field by Japanese battleships. They also evacuated 2,879 casualties during the course of that campaign. Senior commands would have been unwilling to divert the planes from such missions for the time required to train the crews and parachutists for a mass jump in an operation. The Army's transport fleet was equally busy and MacArthur would not assemble enough assets to launch his first parachute assault of the Pacific war until September 1943 (a regimental drop in New Guinea supported by 96 C-47s).

The regiment was unable to do any jumping after May 1943 due to the lack of aircraft. The 2d Battalion's last jump was a night drop from 15 Army Air Corps C-47s. The planes came over Tontouta off course. Unaware of the problem, the Marines jumped out onto a hilly, wooded area. One parachutist died and 11 were injured. Thereafter, the parachutists focused on amphibious operations and ground combat. Lieutenant Colonel Victor H. Krulak drew rubber boats for his 2d Battalion and worked on raider tactics. In late August, I MAC contemplated putting them to work seizing a Japanese seaplane base at Rekata Bay on Santa Isabel, but the enemy evacuated the installation before the intended D-Day.

Near the end of April 1943, Rockey suggested to the Commandant that the Corps disband the parachute school at New River and use its personnel to form the fourth and final battalion. He estimated that production of 30 new jumpers per week at San Diego would be sufficient to maintain field units at full strength. The reduction in school overhead and the training pipeline would relieve some of the pressure on Marine manpower, while the barracks and classroom space at New River would meet the needs of the burgeoning Women's Reserve program. Major General Harry Schmidt, acting in place of Holcomb, signed off on the recommendations. Company B of the 4th Battalion had formed in southern California on 2 April 1943. Nearly all of the 33 officers and 727 enlisted men of the New River school transferred to Camp Pendleton in early July to flesh out the remainder of the battalion. Transport planes were hard to come by in the States, too, and the outfit never conducted a tactical training jump during its brief existence.

|