|

SILK CHUTES AND HARD FIGHTING: US. Marine Corps

Parachute Units in World War II

by Lieutenant Colonel Jon T. Hoffman (USMCR)

Rendezvous at Gavutu

After four months of war, the 1st Marine Division was

alerted to its first prospect of action. The vital Samoan Islands

appeared to be next on the Japanese invasion list and the Navy called

upon the Marines to provide the necessary reinforcements for the meager

garrison. In March 1942, Headquarters created two brigades for the

mission, cutting a regiment and a slice of supporting forces from each

of the two Marine divisions. The 7th Marines got the nod at New River

and became the nucleus of the 3d Brigade. That force initially included

Edson's 1st Raider Battalion, but no paratroopers. In the long run that

was a plus for the 1st Parachute Battalion, which remained relatively

untouched as the brigade siphoned off much of the best manpower and

equipment of the division to bring itself to full readiness. The

division already was reeling from the difficult process of wartime

expansion. In the past few months it had absorbed thousands of newly

minted Marines, subdivided units to create new ones, given up some of

its best assets to field the raiders and parachutists, and built up a

base and training areas from the pine forests of New River, North

Carolina.

The parachutists and the remainder of the division

did not have long to wait for their own call to arms, however. In early

April, Headquarters alerted the 1st Marine Division that it would begin

movement overseas in May. The destination was New Zealand, where

everyone assumed the division would have months to complete the process

of turning raw manpower into well-trained units. Part of the division

shoved off from Norfolk in May. Some elements, including Companies B and

C of the parachutists, took trains to the West Coast and boarded naval

transports there on 19 June. The rest of the 1st Parachute Battalion was

part of a later Norfolk echelon, which set sail for New Zealand on 10

June.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

While the parachutists were still at sea, the advance

echelon of the division had already bedded down in New Zealand. But the

1st Marine Division's commander, Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift,

received a rude shock shortly after he and his staff settled into their

headquarters at a Wellington hotel. He and his outfit were slated to

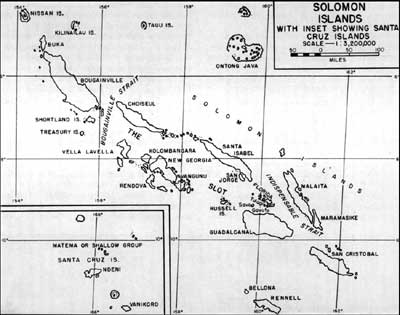

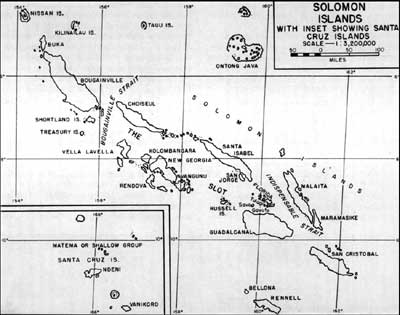

invade and seize islands in the southern Solomons group on 1 August,

just five weeks hence. To complicate matters, there was very little

solid intelligence about the objectives. There were no maps on hand, so

the division had to create its own from poor aerial photos and sketches

hand-drawn by former planters and traders familiar with the area.

Planners estimated that there were about 5,275 enemy

on Guadalcanal (home to a Japanese air field under construction) and a

total of 1,850 on Tulagi and Gavutu-Tanambogo. Tulagi, 17 miles north of

Guadalcanal, was valuable for its anchorage and seaplane base. The

islets of Gavutu and Tanambogo, joined by a causeway, hosted a sea plane

base and Japanese shore installations and menaced the approaches to

Tulagi. In reality, there were probably 536 men on Gavutu Tanambogo,

most of them part of construction or aviation support units, though

there was at least one platoon of the 3d Kure Special Naval Landing

Force, the ground combat arm of the Imperial Navy. The list of heavy

weapons on Gavutu Tanambogo included two three-inch guns and an

assortment of antiaircraft and antitank guns and machine guns.

By the time the last transports docked in New Zealand

on 11 July, planners had outlined the operation and the execution date

bad slipped to 7 August to allow the division a chance to gather its

far-flung echelons and combat load transports. Five battalions of the

1st and 5th Marines would land on the large island of Guadalcanal at

0800 on 7 August and seize the unfinished airfield on the north coast.

The 1st Raider Battalion, slated to meet the division on the way to the

objective, would simultaneously assault Tulagi. The 2d Battalion, 5th

Marines, would follow in trace and support the raiders. The 2d Marines,

also scheduled to rendezvous with the division at sea, would serve as

the reserve force and land 20 minutes prior to H-Hour on Florida Island,

thought to be undefended. The parachutists received the mission of

attacking Gavutu at H plus four hours. The delay resulted from the need

for planes, ships, and landing craft to concentrate first in support of

the Tulagi operation. Once the paratroopers secured Gavutu, they would

move on to its sister. The Tulagi, Gavutu-Tanambogo, and Florida

operations fell under the immediate control of a task force designated

as the Northern Group, headed by Brigadier General William H. Rupertus,

the assistant division commander.

|

Marine Parachute Pioneers

In October 1940, the Commandant sent a circular

letter to all units and posts to solicit volunteers for the

paratroopers. All applicants, with the exception of officers above the

rank of captain, had to meet a number of requirements regarding age (21

to 32 years), height (66 to 74 inches), and health (normal eyesight and

blood pressure). In addition, they had to be unmarried, an indication

of the expected hazards of the duty. Applications were to include

information on the Marine's educational record and athletic experience,

so Headquarters was obviously interested in placing above-average

individuals in these new units.

The letter further stated that personnel qualified as

parachutists would receive an unspecified amount of extra pay. The

money served as both a recognition of the danger and an incentive to

volunteer. Congress would eventually set the additional monthly for

parachutists at $100 for officers and $50 for enlisted men. Since a

private first class at that time earned about $36 per month and a second

lieutenant $125, the increase amounted to a hefty bonus. It would prove

to be a significant factor in attracting volunteers, though parachuting

would have generated a lot of interest without the money. As one early

applicant later put it, based on common knowledge of the German success

in the Low Countries, many Marines thought "that this was going to be a

grand and glorious business." Parachute duty promised "plenty of

action" and the chance to get in on the ground floor of a revolutionary

type of warfare.

To get the program underway, the Commandant

transferred Marine Captain Marion L. Dawson from duty with the Navy's

Bureau of Aeronautics to Lakehurst, New Jersey, to oversee the new

school. Two enlisted Marine parachute riggers would serve as his

initial assistants. Marine parachuting got off to an inauspicious start

when Captain Dawson and two lieutenants made a visit to Hightstown, New

Jersey, to check out the jumping towers. The other officers, Second

Lieutenants Walter S. Osipoff and Robert C. McDonough, were slated to

head the Corps' first group of parachute trainees. After watching a

brief demonstration, the owner suggested that the Marines give it a

test. As Dawson later recalled, he "reluctantly" agreed, only to break

his leg when he landed at the end of his free fall.

On 26 October 1940, Osipoff, McDonough, and 38

enlisted men reported to Lakehurst. The Corps was still developing its

training program, so the initial class spent 10 days at Highstown

starting on 28 October. Immediately after that they joined a new class

at the Parachute Material School land followed that 16-week coursed of

instruction until its completion on 27 February 1941. A Douglas R3D-2

transport plane arrived from Quantico on 6 December and remained there

through the 21st, so the pioneer Marine paratroopers made their first

jumps during this period. For the remainder of the course, they leapt

from Navy blimps stationed at Lakehurst. Lieutenant Osipoff, the senior

officer, had the honor of making the first jump by a Marine paratrooper.

By graduation, each man had completed the requisite 10 jumps to qualify

as a parachutist and parachute rigger. Not all made it through —

several dropped from the program due to ineptitude or injury. The

majority of these first graduates were destined to remain at Lakehurst

as instructors or to serve the units in the Fleet Marine Force as

riggers.

By the time the second training class reported,

Dawson and his growing staff had created a syllabus for the program.

The first two weeks were ground school, which emphasized conditioning,

wearing of the harness, landing techniques, dealing with wind drag of

the parachute once on the ground, jumping from platforms and a plane

mockup, and packing chutes. Students spent the third week riding a bus

each day to Highstown where they applied their skills on the towers.

The final two weeks consisted of work from aircraft and tactical

training as time permitted. Students had to complete six jumps to

qualify as a parachutist. The trainers had accumulated their knowledge

from the Navy staff, from observing Army training at Fort Benning, and

from a film depicting German parachutists. The latter resulted in one

significant Marine departure from U.S. Army methods. Whereas the Army

made a vertical exit from the aircraft, basically just stepping out the

door, Marines copied the technique depicted in the German film and tried

to make a near-perpendicular dive, somewhat like a simmer coming off the

starting block.

Marine paratroopers used two parachutes in training

and in tactical jumps. They wore the main chute in a backpack

configuration and a reverse chute on their chest. When jumping from

transport planes, the main opened by means of a static line attached to

a cable running lengthwise in the cargo compartment. Once the

jumpmaster gave the signal, a man crouched in the doorway, made his exit

dive, and then drew his knees toward his chest. The parachutist, arms

wrapped tightly about his chest chute, felt the opening shock of his

main canopy almost immediately upon leaving the plane. If not, he had

to pull the ripcord to deploy the reserve chute. (When jumping from

blimps, the parachutists had to use a ripcord for the main chute too.)

A parachutist's speed of descent depended upon his weight, so Marines

carried as little as possible to keep the rate down near 16 feet per

second, the equivalent of jumping from a height of about 10 feet. At

that speed a jumper had to fall and roll when hitting the ground so as

to spread the shock beyond his leg joints. Training jumps began at 1,000

feet, while the standard height for tactical jumps in the Corps was 750

feet. The Germans jumped from as low as 300 feet, but that made it

impossible to open the emergency chute in time for it to be

effective.

|

After a feverish week of unloading, sorting, and

reloading equipment and supplies, the parachutists boarded the transport

USS Heywood on 18 July and sailed in convoy to Koro Island in the

Fijis, where the entire invasion force conducted landing rehearsals on

28 and 30 July. These went poorly, since the Navy boat crews and most of

the 1st Marine Division were too green. The parachute battalion was

better trained than most of the division, but this was its very first

experience as a unit in conducting a seaborne landing. There is no

indication that planners gave any thought to using their airborne

capability, though in all likelihood that was due to the lack of

transport aircraft or the inability of available planes to make a

round-trip flight from New Zealand to the Solomons.

|