| Marines in World War II |

|

SILK CHUTES AND HARD FIGHTING: US. Marine Corps Parachute Units in World War II by Lieutenant Colonel Jon T. Hoffman (USMCR) Edson's Ridge On 9 September, Edson met with division planners to discuss the results of the raid. Intelligence officers translating captured documents indicated that up to 3,000 Japanese were cutting their way through the jungle southwest of Tasimboko. Edson was convinced that they planned to attack the unguarded southern portion of the perimeter. From an aerial photograph he picked out a grass-covered ridge that pointed like a knife at the airfield. He based his hunch on his experience with the Japanese and in jungle operations in Nicaragua. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas agreed. Vandegrift, just in the process of moving his command post into that area, was reluctant to accept a conclusion that would force him to move yet again. After much discussion, he allowed Thomas to shift the bivouac of the raiders and parachutists to the ridge to get them out of the pattern of bombs falling around the airfield.

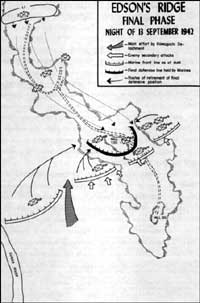

The combined force moved to the new location on 10 September and quickly discovered that it was not the rest area they had hoped to enjoy. Orders came down from Edson to dig in and enemy aircraft bombed the ridge on the 11th and 12th, inflicting several casualties. Native scouts reported the progress of the Japanese column and Marine patrols confirmed the presence of strong enemy forces to the southeast of the perimeter. The raiders and parachutists found the process of constructing defensive positions tough going. There was very little barbed wire and no sand bags or heavy tools. Men digging in on the ridge itself found coral just below the shallow surface soil. Units disposed in the flanking jungle were hampered by the thick growth, which reduced fields of fire to nothing. Both units were smaller than ever, as tropical illnesses, poor diet, and lack of sleep combined to swell the number of men in the field hospital. Those still listed as effective often were just barely so. Edson faced a tough situation as he contemplated how to defend the ridge area. Several hundred yards to the right of his coral hogback was the Lunga River; beyond it, elements of the 1st Pioneer and 1st Amphibious Tractor Battalions had strongpoints. More than a mile to his left was the tail end of the 1st Marine Regiment's positions along the Tenaru River. With the exception of the kunai grass-covered slopes of the ridge, everything else was dense jungle. His small force, about the size of a single infantry battalion but lacking all the heavy weapons, could not possibly establish a classic linear defense. Edson placed the parachutists on the east side of the ridge, with Company B holding a line running from the slope of Hill 80 into the jungle. The other two companies echeloned to the rear to hold the left flank. Company B of the raiders occupied the right slope of Hill 80 and anchored their right on a lagoon. Company C placed platoon strongpoints between the lagoon and river. The remaining raiders were in reserve near Hill 120. Thomas moved 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, into position between the ridge and the airfield and reoriented some of his artillery to fire to the south. Artillery forward observers joined Edson's command post on the front slope of Hill 120 and registered the guns. Kawaguchi's Brigade faced its own troubles as it fought through the jungle and over the numerous slimy ridges. The rough terrain had forced the Japanese to leave behind their artillery and most of their supplies. Their commander also detailed one of his four battalions to make a diversionary attack along the Tenaru, which left him with just 2,500 men for the main assault. To make matters worse, the Japanese had underestimated the jungle and fallen behind schedule. As the sunset on 12 September, Kawaguchi realized that only one battalion was in its assembly area and none of his units had been able to reconnoiter their routes of attack. The Japanese general tried to delay the jumpoff scheduled for 2200, hut he could not contact his battalions. Without guides and running late, the attack blundered for ward in darkness and soon degenerated into con fusion. At the appointed hour, a Japanese float plane dropped green flares over the Marine positions. A cruiser and three destroyers began shelling the ridge area and kept up the bombardment for 20 minutes, though few rounds landed on their intended target; many sailed over the ridge into the jungle beyond. Japanese infantry followed up with their own flares and began to launch their assault. The enemy's confusion may have benefited the parachute battalion, since all the action occurred on the raider side of the position. The enemy never struck the ridge proper, but did dislodge the Company C raiders, who fell back and eventually regrouped near Hill 120. At daylight the Japanese broke off the attack and tried to reorganize for another attempt the next night.

In the morning, Edson ordered a counterattack by the raiders of Company B and the parachutists of Company A to recapture Company C's position. The far more numerous Japanese stopped them cold with machine gun fire. Since he could not eject the Japanese from a portion of his old front, the raider commander decided to withdraw the entire line to the reserve position. In the late afternoon the Companies B of both raiders and parachutists pulled back and anchored themselves on the ridge between Hills 80 and 120. Division provided an engineer company, which Edson inserted on the right of the ridge. Company A of the raiders covered the remaining ground to the Lunga. Company C parachutists occupied a draw just to the left rear of their own Company B, while Company A held another draw on the east side of Hill 120. The raiders of Companies C and D assumed a new reserve position on the west slope of the ridge, just behind Hill 120. Edson's forward command post was just in front of the top of Hill 120. Kawaguchi renewed his attack right after darkness fell on the 13th. His first blow struck the right flank of the raiders' Company B and drove more than a platoon of those Marines out of their positions. Most linked up with Company C in their rear, while the remainder of Company B clung to its position in the center of the ridge. The Japanese did not exploit the gap, except to send some infiltrators into the rear of the raider and parachute line. They apparently cut some of the phone lines running from Edson's command post to his companies, though he was able to warn the parachutists of the threat in their rear. By 2100 the Japanese obviously were massing around the southern nose of the ridge, lapping around the flanks of the two B Companies and making their presence known with firecrackers, flares, "a hellish bedlam of howls," and rhythmic chanting designed to strike fear into the heart of their enemy and draw return fire for the purpose of pinpointing automatic weapons. Edson responded with a fierce artillery barrage and orders to Company C raiders and Company A parachutists to form a reserve line around the front and sides of Hill 120. As Japanese mortar and machine gun fire swept the ridge, Captain William J. McKennan and First Sergeant Marion LeNoir gathered their paratroopers and led them into position around the knoll.

The Japanese assault waves finally surged forward around 2200. The attack, focused on the open ground of the ridge, immediately unhinged the remainder of the Marine center. Captain Justin G. Duryea, commanding the Company B parachutists, ordered his men to withdraw as Marine artillery shells fell ever closer to the front lines and Japanese infantry swarmed around his left flank. He also believed that the remainder of the Company B raiders already were falling back on his right. To add to the confusion, Marines thought they heard shouts of "gas attack" as smoke rose up from the lower reaches of the ridge. Duryea's small force ended up next to Company C in the draw on the east slope, where he reported to Torgerson, now the battalion executive officer. The units were clustered in low-lying ground and had no contact on their flanks. Torgerson ordered both companies to withdraw to the rear of Hill 120, where he hoped to reorganize them in the lee of the reserve line and the masking terrain. Given the collapse of the front line, it was a reasonable course of action. The withdrawal of the parachutists left the rump of the raiders, perhaps 60 men, all alone in the center of the old front line. Edson arranged for covering fire from the artillery and the troops around Hill 120, then ordered Company B back to the knoll. There they joined the reserve line, which was now the new front line. This series of rearward movements threatened to degenerate into a rout. Night movements under fire are always confusing and commanders no longer had positive control of coherent units. There was no neat line of fighting holes to occupy, no time to hold muster and sort out raiders from parachutists and get squads, platoons, and companies back together again. A few men began to filter to the rear of the hill, while others lay prone waiting for direction. Edson, with his command post now in the middle of the front line, took immediate action. The raider commander ordered Torgerson to lead his Companies B and C from the rear of the hill and lengthen the line running from the left of Company A's position. Edson then made it known that this would he the final stand, that no one was authorized to retreat another step. Major Kenneth D. Bailey, commander of the Company C raiders, played a major role in revitalizing the defenders. He moved along the line of mingled raiders and parachutists, encouraging everyone and breathing new life into those on the verge of giving up. Under the direction of Torgerson and unit leaders, the two parachute companies in reserve moved forward in a skirmish line and established contact on the flank of their fellows from Company A. They met only "slight resistance" in the process, but soon came under heavy attack as the Japanese renewed their assault on the hill. Edson later thought that this action "succeeded in breaking up a threatening hostile envelopment of our position" and "was a decisive factor in our ultimate victory." The new line of raiders and parachutists was not very strong, just a small horseshoe bent around the bare slopes of the knoll, with troops from the two battalions still intermingled in many spots. The artillery kept up a steady barrage — "the most intensive concentration of the campaign" according to the division's final report. And all along the line, Marines threw grenade after grenade to support the fire of their automatic weapons. Supplies of ammunition dwindled rapidly and moving cases of grenades and belted machine gun rounds to the frontline became a key element of the fight. At 0400, Edson asked division to commit the reserve battalion to bolster his depleted forces. One company at a time, the men of the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, moved along the spine of the ridge and into place beside those who had survived the long night. By dawn the Japanese had exhausted their reservoir of fighting spirit and Kawaguchi admitted defeat in the face of a tenacious defense backed by superior firepower. The enemy began to break contact and retreat, although a number of small groups and individuals remained scattered through the jungle on the flanks and in the rear of the Marine position. The men of the 2d Battalion began the long process of rooting out these snipers, while Edson ordered up an air strike to hasten the departure of the main Japanese force. A flight of P-40s answered the call and strafed the enemy infantry still clinging to the exposed forward slopes of Hill 80. The raiders and parachutists walked off the ridge that morning and returned to their previous bivouac in the coconut grove. Although an accurate count of Japanese bodies was impossible, the division estimated there were some 700 dead sprawled around the small battlefield. Of Kawaguchi's 500 wounded, few would survive the difficult trek back to the coast.

The two-day battle on the ridge had cost the 1st Raiders 135 men and the 1st Parachute Battalion 128. Of those totals, 59 were dead or missing, including 15 parachutists killed in action. Many of the wounded parachutists would eventually return to duty, but for the moment the battalion was down to about 100 effectives, the equivalent of a severely under-strength rifle company. It was no longer a useful tactical entity and had seen its last action on Guadalcanal. Three days later, a convoy brought the 7th Marines to the island and the remaining men of the 1st Parachute Battalion embarked in those ships for a voyage to a welcome period of rest and recuperation in a rear area. The parachute battalion had contributed a great deal to the successful prosecution of the campaign. They had made the first American amphibious assault of the war against a defended beach and fought through the intense fire to secure the island. Despite their meager numbers, lack of senior leadership, and minimal firepower, they had stood with the raiders against difficult odds on the ridge. The 1st Marine Division's final report on Guadalcanal lauded that performance: "The actions and conduct of those who participated in the defense of the ridge is deserving of the warmest commendation. The troops engaged were tired, sleepless and battle weary at the outset. Throughout the night they held their positions in the face of powerful attacks by over whelming numbers of the enemy. Driven from one position they reorganized and clung tenaciously to another until daylight found the enemy again in full flight." Looking back on the campaign after the war, General Vandegrift would say that "I think the most crucial moment was the Battle of the Ridge."

|