| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

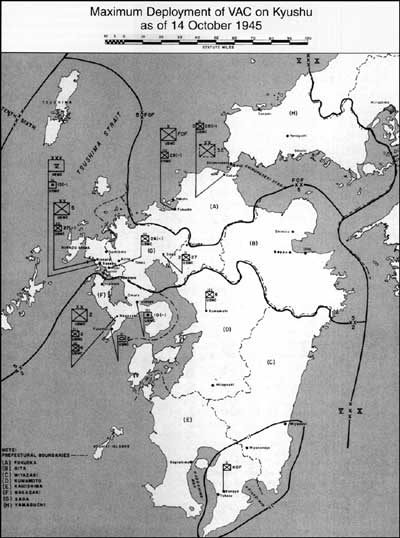

SECURING THE SURRENDER: Marines in the Occupation of Japan by Charles R. Smith Kyushu Occupation The V Amphibious Corps zone of occupation comprised the entire island of Kyushu and Yamaguchi Prefecture on the western tip of Honshu. After the 2d and 5th Marine Divisions had landed, General Schmidt's general plan was for Major General Hunt's 2d Marine Division to expand south of the city of Nagasaki and assume control of Nagasaki, Kumamoto, Miyazaki, and Kagoshima Prefectures. In the meantime, Major General Bourke's 5th Marine Division was to expand east to the prefectures of Saga, Fukuoka, Oita, and Yamaguchi. Bourke's troops were to be relieved in the Fukuoka, Otia, and Yamaguchi areas with the arrival of sufficient elements of Major General William H. Gill's veteran 32d Infantry Division. Preliminary plans for the occupation of Japan had contemplated the establishment of a formal allied military government, similar to that in operation in Germany, coupled with the direct supervision of the disarmament and demobilization of the Japanese Armed Forces. However, during the course of discussions with enemy emissaries in Manila, radical modifications of these plans were made "based on the full cooperation of the Japanese and [including] measures designed to avoid incidents which might result in renewed conflict." Instead of instituting direct military rule, occupation force commanders were to supervise the execution of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers' directives to the Japanese government, keeping in mind Mac Arthur's policy of using, but not supporting, the government. Enemy military forces were to be disarmed and demobilized under their own supervision, and the progressive occupation of assigned areas by Allied troops was to be accomplished as Japanese demobilization was completed. The Japanese government and its armed forces were to shoulder the chief administrative and operational burden of disarmament and demobilization. The infantry regiment, and division artillery operating as infantry, was to be "the chief instrument of demilitarization and control. The entire plan for the imposition of the terms of surrender was based upon the presence of infantry regiments in all the prefectures with in the Japanese homeland." Within the Sixth Army zone, occupational duties were fairly standardized. The division of responsibilities was based upon the boundaries of the prefectures so that the existing Japanese governmental structure could be used. The Sixth Army assigned a number of prefectures to each corps proportionate to the number of troops available. The corps, in turn, assigned a specific number of prefectures to a division. Regiments, usually, were given responsibility for a single prefecture. In the 5th Marine Division zone of responsibility, however, the size of certain prefectures, the large civilian population, and the tactical necessities of troop deployment combined to force modifications of the general scheme of regimental responsibility for a single prefecture. The regiment's method of carrying out its occupational mission varied little between zones and units whether Army or Marine. As a corps extended its zone of responsibility, advance parties, composed of specialized staff officers from higher headquarters and the unit involved, were sent into areas to be occupied. Liaison was established with local Japanese civil and military authorities who provided the parties with information on transportation and harbor facilities, inventories of arms and supplies, and the location of dumps and installations. With this information in hand, the regiment then moved into a bivouac area in or near its zone of responsibility. Reconnaissance patrols consisting of an officer and a rifle squad were sent out to verify the location of reported military installations and check inventories of war materiel and also to search for any unreported facilities and materiel caches. The regimental commander then divided his zone into battalion areas, and battalion commanders could, in turn, assign their companies specific sectors of responsibility. Sanitation details preceded the troops into the areas to oversee the preparation of barracks and messing facilities, since many of the installations to be occupied were in a deplorable condition and insect-ridden. The infantry company or artillery battery thus became the working unit which actually accomplished the destruction or transfer of war materiel and the demobilization of Japanese Armed Forces. Company commanders were empowered to seize military installations within the company zone and, using Japanese military personnel not yet demobilized and laborers obtained through the local Japanese Home Ministry representative, either destroy or turn over to the Home Ministry all materiel within the installation. All war materiel was divided into five categories and was to be disposed of according to SCAP Ordnance and Technical Division directives. The categories were: that to be destroyed or scrapped, such as explosives and armaments not needed for souvenirs or training purposes; that to be used for allied operations, such as telephones, radios, and vehicles; that to be returned to the Japanese Home Ministry, which encompassed food, fuel, clothing, lumber, and medical supplies; that to be issued as trophies; and that to be shipped to the United States as trophies or training gear.

The hazardous job of disposing of explosive ordnance was to be handled by the Japanese with a minimum of American supervision. Explosives were either burned in approved areas, sealed in place if stored in tunnels, or dumped at sea — the latter being the preferred method. Because of the large quantity of ammunition to be disposed of on Kyushu, both divisions would experience difficulties. Japanese shipping was not available in sufficient strength for dumping the ammunition at sea and the large ammunition could not be blown up as there were no suitable areas in which to detonate it safely. Metal items declared surplus were to be rendered ineffective, by Japanese labor, and turned over to the Japanese as scrap for peacetime civilian uses. Food items and other nonmilitary stocks were to be returned to the Japanese for the relief of the local civilian population. While local police were given the responsibility of maintaining law and order and enforcing SCAP democratization decrees, Allied forces were to maintain a constant surveillance over Japanese methods of government. Intelligence and military government personnel, working with the occupying troops, were tasked with stamping out any hint of a return to militarism, looking for evidence of evasion or avoidance of the surrender terms, and detecting and suppressing movements considered detrimental to the interests of allied forces. Known or suspected war criminals were to be apprehended and sent to Tokyo for processing and possible arraignment before an allied tribunal. In addition, occupation forces were responsible for insuring the smooth processing of hundreds of thousands of military personnel and civilians returning from Japan's now defunct Empire. Repatriation centers would be established at Kagoshima, Hario near Sasebo, and Hakata near Fukuoka. Each incoming soldier or sailor would be sprayed with DDT, examined and inoculated for typhus and smallpox, provided with food, and transported to his final destination in Japan. Both line and medical personnel were assigned to supervise the Japanese-run centers. At the same time thousands of Korean and Chinese prisoners and conscript laborers had to be collected and returned to their homelands. In the repatriation operations, Japanese vessels and crews would be used to the fullest extent possible to conserve Allied manpower and allow for an accelerated program of postwar demobilization.

This pattern of progressive occupation was quickly established in V Amphibious Corps zone of responsibility. During the last days of September, both of the Corps' divisions concentrated on unloading at Sasebo and Nagasaki, moving supplies into dumps, organizing billeting areas, securing local military installations, and preparing elements for the expansion eastward. In addition to normal occupation duties, both divisions became saddled with the job of unloading "a terrific amount of shipping." As Lieutenant Colonel Jacob Goldberg wrote at the time: "we are building up a mountain of supplies consisting of items we will never be able to use and I can fore see the day when we just leave it all for the Japs . . . . Everyone in the Pacific is apparently getting rid of their excess materiel by shipping it to Japan, regardless of whether anyone in Japan needs it. One word describes the situation: SNAFU." Confirming Goldberg's assessment, Major Norman Hatch later noted that the Marines, after days on C- and K-rations were getting "fed up with this, and occasionally a big refrigerator ship would come in and everybody would say, . . . 'Now we'll get some fresh food,' but we'd find that the cold lockers were loaded with barbed wire, ping pong balls, things of that nature . . . .What we would do with barbed wire in Japan nobody had the slightest idea."

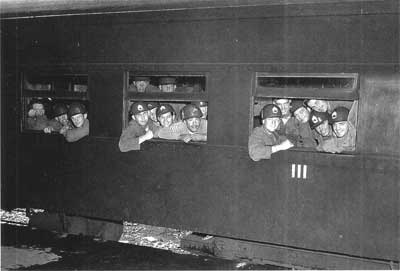

On 25 September, two days after landing at Sasebo, General Bourke's division began expanding its assigned zone of occupation and patrols were sent into outlaying areas. The Marines found Japanese civilian and military personnel to be cooperative, but as they initially found in the city, most women and children in rural areas appeared frightened. As the Japanese grew accustomed to the Marine presence and more assured that they would not be harmed, their initial shyness and fear soon disappeared. During the next few days, all main routes within the division's zone were covered even though most were in poor repair, "some not negotiable by anything but jeeps." As the expansion continued, Japanese guards were relieved at military installations and storage areas; the inventorying of Japanese equipment was begun; liaison was established with local military and civilian leaders; and Marine guards were stationed at post offices and city halls. Within a week of landing, the division's zone of responsibility again was expanded to include Yagahara, Miyazaki, Arita, Takeo, Saishi, Sechihara, Imabuku, and a number of other towns to the north and west of Sasebo. On 29 September, the division's zone was enlarged further to include Fukuoka, the largest city on Kyushu and administrative center of the northwestern coal and steel region. Since Fukuoka harbor was littered with pressure mines dropped by American Air Forces, movement to the city was made by rail and road instead of by ship from Sasebo. An advance billeting and reconnaissance party, headed by Colonel Walter Wensinger, reached Fukuoka on 27 September and held preliminary meetings with local civil and military officials. Brigadier General Ray A. Robinson, the division's assistant commander, was given command of the Fukuoka region occupation force which consisted of the 28th Marines reinforced with artillery and engineers and augmented by Army detachments. Lead elements of Robinson's force began arriving on the 30th, and by 5 October the force had completed the move from Sasebo. "All the way up [to Fukuoka]," as General Robinson recalled later, "when we stopped at a station, the equivalent of our Red Cross girls, these Japanese women, would come down with tea and cakes. They'd been our enemies . . . so we thought they were going to poison us, so nobody took 'em!"

The Fukuoka Occupation Force, which was placed directly under General Schmidt's command, immediately began sending reconnaissance parties followed by company and battalion-sized forces into the major cities of northern Kyushu. But because of the limited number of troops available and the large area to be covered, Japanese guards were left in charge of most military installations, and effective control of the zone was maintained by motorized patrols. To prevent possible outbreaks of mob violence, Marine guard detachments were set up to administer Chinese labor camps found in the area, and Japanese Army supplies were requisitioned to feed and clothe the former prisoners of war and laborers. Some of the supplies also were given to the thousands of Koreans who had gathered in temporary camps near the principal repatriation ports of Fukuoka and Senzaki in Yamaguchi Prefecture, where they waited for ships to carry them back to their homeland. The Marines, in addition to supervising the loading out of the Koreans, checked on the processing and discharge procedures used to handle Japanese troops returning with each incoming vessel. In addition, the branches of the Bank of Chosen were seized and closed in an effort to crush suspected illegal foreign exchange operations. Like their counterparts in other areas of Kyushu. Robinson's occupation force located and inventoried vast quantities of Japanese war materiel for later disposition by the 32d Infantry Division.

|