| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

SECURING THE SURRENDER: Marines in the Occupation of Japan by Charles R. Smith When not engaged in renovating the air base or on air missions, liberty parties were organized and sent by boat to Tokyo. Preference was given to personnel who were expected to return to the United States for discharge. Fraternzation, although originally forbidden by the American high command, was allowed after the first week. "The Japanese Geisha girls have taken a large share of the attention of the many curious sight-seers of the squadron," reported Major Michael R. Yunck, commanding officer of Marine Fighter Squadron 311. "The Oriental way of life is something very hard for an American to comprehend. The opinions on how the occupation job 'should be done' range from the most generous to the most drastic — all agreeing on one thing, though, that it is a very interesting experience." Prostitution and the resultant widespread incidence of venereal diseases were ages old in Japan. "The world's oldest profession" was legal and controlled by the Japanese government; licensed prostitutes were confined to restricted sections. Placing these sections out of bounds to American forces did not solve the problem of venereal exposure, for, as in all ports such as Yokosuka, clandestine prostitution continued to flourish. In an attempt to prevent uncontrolled exposure, all waterfront and backstreet houses of prostitution were placed out of bounds. A prophylaxis station was established at the entrance to a Japanese police-controlled "Yashuura House" (a house of prostitution exclusively for the use of occupation forces), another in the center of the Yokosuka liberty zone, and a third at the fleet landing. These stations were manned by hospital corpsmen under the supervision of a full-time venereal disease-prevention medical officer. In addition, a continuous educational campaign was carried out urging continence and warning of the dangerous diseased condition of prostitutes. These procedures resulted in a drastic decline in reported cases of diseases originating in the Yokosuka area.

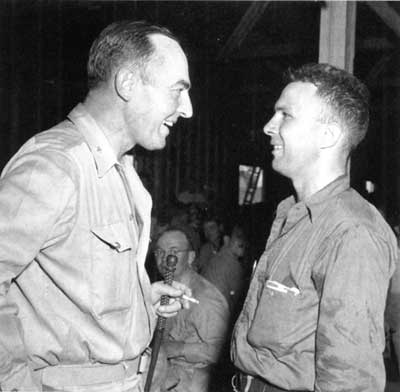

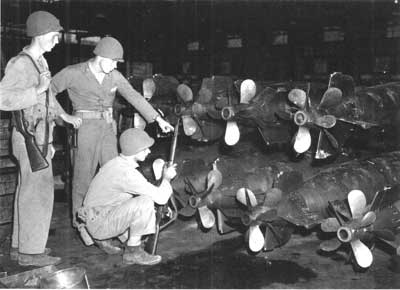

On 8 September, the group's Corsairs and Hellcats, stripped of about two and a half tons of combat weight, began surveillance flights over the Tokyo Bay area and the Kanto Plain north of the capital. The purpose of the missions was to observe and report any unusual activity by Japanese military forces and to survey all airfields in the area. Initially, Munn's planes served under Third Fleet command, but on the 16th, operational control of MAG-31 was transferred to the Fifth Air Force. A month later, the group was returned to Navy control and reconnaissance flights in the Tokyo area and Kanto Plain discontinued. Operations of the air group were confined largely to mail, courier, transport, and training flights to include navigation, tactics, dummy gunnery, and ground control approach practice. By mid-October, the physical condition of the base had been improved to such an extent that the facilities were adequate to accommodate the remainder of the group's personnel. On 7 December, the group's four tactical squadrons were placed under the operational control of the Far Eastern Air Force and surveillance and reconnaissance flights again resumed. On 8 September, Admiral Badger's Task Force 31 was dissolved and the Commander, Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, assumed responsibility for the naval occupation area. General Clement's command, again designated Task Force Able, continued to function for a short time thereafter while most of the reinforcing units of the 4th Marines loaded out for return to Guam. On the 20th, Lieutenant Colonel Beans relieved General Clement of his responsibilities at Yokosuka, and the general and his staff flew back to Guam to rejoin the 6th Division. Before he left, Clement was able to take part in a ceremony honoring more than 120 officers and men of the "Old" 4th Marines, captured on Bataan and Corregidor.

After the initial major contribution of naval land forces to the occupation of northern Japan, the operation became more and more an Army task. As additional troops arrived, the Eighth Army's area of effective control grew to encompass all of northern Japan. In October, the occupation zone of the 4th Marines was reduced to include only the naval base, airfield, and town of Yokosuka. In effect, the regiment became a naval base guard detachment, and on 1 November, control of the 4th Marines passed from Eighth Army to the Commander, U.S. Fleet Activities, Yokosuka. While the Marine presence gradually diminished, activity in the surrounding area began to return to normal. Japanese civilians started returning to the city of Yokosuka in large numbers. "The almost universal attitude was at first one of timidity and fear, then curiosity," it was reported. "Banks opened and started to operate . . . . Post offices and telegraph offices started to function smoothly, and movie houses began to fill with civilian crowds." Unlike Tokyo and Yokohama, the Yokosuka area had escaped much destruction and was remarkably intact. On base, evacuated Japanese barracks were quickly cleaned up and made reasonably liveable. The Japanese furnished cooks, mess boys, and housekeeping help, allowing Marines more time to explore the rice-paddy and beach resort-dotted countryside, and liberty in town. Allowed only five hours liberty three times a week, most enlisted Marines saw little of Japan, except for short sight-seeing tours to Tokyo or Kamakura. Yokosuka, a small city with long beer lines, quickly lost its novelty and Yokohama was off limits to enlisted personnel. So most Marines would "have a few brews and head back for the base at 4 p.m. when the beer sales cease." Their behavior was remarkable considering only a few months before they had fought a hard and bloody battle on Okinawa. Crimes against the local Japanese population were few and, for the most part, petty. It was the replacement, not the combat veteran, who, after a few beers, would "slug a Jap" or curse them to their faces.

|