| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

SECURING THE SURRENDER: Marines in the Occupation of Japan by Charles R. Smith Of the few problems, two stood out — rape and the black market. Japanese women, so subdued, if propositioned would comply and later charge "rape." "Our courts gave severe sentences, which I approved," noted one senior commander. "This satisfied the Japanese honor. I expected the sentences to be greatly reduced, as they were, in the United States. The sooner these men were returned home, the better for all hands, including the Japanese." In addition, the utter lack and concomitant demand for consumer goods caused some Marines to smuggle items, such as cigarettes, out to the civilian market where they brought a high price. Although attempts were made to curb the practice, many unnecessary and expensive courts-martial where held "which branded our men with bad conduct discharges."

In addition to routine duties and security and military police patrols, the Marines also carried out Eighth Army demilitarization directives, collecting and disposing of Japanese military and naval materiel. In addition, they searched their area of responsibility for caches of gold, silver, and platinum. During the search, no official naval records, other than inventories and a few maps and charts, were found. It was later learned that the Japanese had been ordered to burn or destroy all documents of military value to the Allies. The surrender of all garrisons having been taken, motorized patrols with truck convoys were sent out to collect as many small arms, weapons, and as much ammunition as possible. The large amount of such supplies in the Yokosuka area made the task an extensive one. In addition, weekly patrols from the regiment supervised the unloading at Uraga of Japanese troops and civilians returning from such by passed Pacific outposts as Wake, Yap, and Truk. Although there was concern that some Japanese soldiers might cause trouble, none did. On 20 November, the 4th Marines was removed from the administrative control of the 6th Division and placed directly under FMFPac. Orders were received directing that preparations be made for 3d Battalion to relieve the regiment of its duties in Japan, effective 31 December. In common with the rest of the Armed Forces, the Marine Corps faced great public and Congressional pressure to send its men home for discharge as rapidly as possible. The Corps' world-wide commitments had to be examined with this in mind. The Japanese attitude of cooperation with occupation authorities fortunately permitted considerable reduction of troop strength. In Yokosuka, Marines who did not meet the age, service, or dependency point totals necessary for discharge in December or January were transferred to the 3d Battalion, while men with the requisite number of points were concentrated in the 1st and 2d Battalions.

On 1 December, the 1st Battalion completed embarkation on board the carrier Lexington (CV 16) and sailed for the West Coast to be disbanded. On the 24th, the 3d Battalion, reinforced by regimental units and a casual company formed to provide replacements for Fifth Fleet Marine detachments, relieved 2d Battalion of all guard responsibilities. The 2d Battalion, with Regimental Weapons and Headquarters and Service Companies, began loading out operations on the 27th and sailed for the United States on board the attack cargo ship Lumen (AKA 30) on New Year's Day. Like the 1st, the 2d Battalion and the accompanying two units would be disbanded. All received war trophies: Japanese rifles and bayonets were issued to enlisted men; officers received swords less than 100 years old; pistols were not issued and field glasses were restricted to general officers. At midnight on 31 December, Lieutenant Colonel Bruno A. Hochmuth, the regiment's executive officer, took command of the 3d Battalion, as the battalion assumed responsibility for the security of the Naval Station, Marine Air Base, and the city of Yokosuka. A token regimental headquarters remained behind to carry on the name of the 4th Marines. Six days later, the headquarters detachment left Japan to rejoin the 6th Marine Division then in Tsingtao, China. On 15 February, the 3d Battalion was redesignated the 2d Separate Guard Battalion (Provisional), Fleet Marine Force, Pacific. An internal reorganization was carried out and the battalion was broken down into guard companies. Its military police and security duties in the naval base area and city of Yokosuka remained the same. The major task of demilitarization in the naval base having been completed, the battalion settled into a routine of guard duty, ceremonies, and training, little different from that of any Navy yard barracks detachment in the United States.

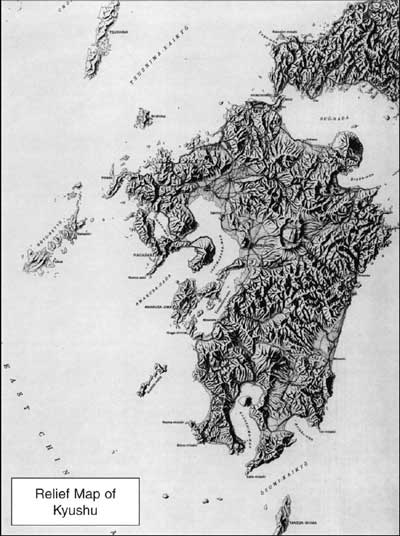

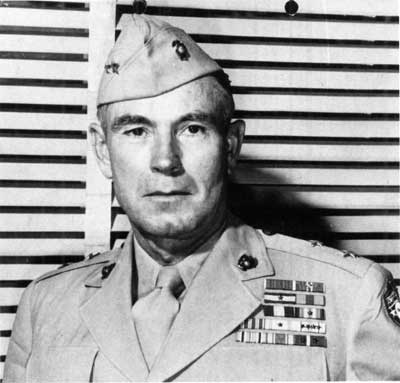

In January, the Submarine Base was returned to Japanese control. With the return of the Torpedo School-Supply Base Area, the relief of all gate posts by naval guards, and the detachment of more than 300 officers and men in March, the 2d and 4th Guard Companies were disbanded and the security detail drawn from a consolidated 1st Guard Company. On 1 April, MAG-31 relieved the 3d Guard Company of security responsibility for the Air Base and the company was disbanded. With additional drafts of personnel for discharge or reassignment and an order to reduce the Marine strength to 100, the Commander, U.S. Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, responded. "I reacted," Captain Benton W. Decker later wrote, "reporting that the security of the base would be jeopardized and that 400 Marines were necessary, whereupon the order was canceled, and a colonel was ordered to relieve Lieutenant Colonel Bruno Hochmuth. Again, I insisted that Lieutenant Colonel Hochmuth was capable of commanding my Marine unit to my complete satisfaction, so again, Washington canceled an order." On 15 June, the battalion, reduced in strength to 24 officers and 400 men, was redesignated Marine Detachment, U.S. Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, Lieutenant Colonel Hochmuth commanding. The Senior Marine Commanders The three senior Marine commanders on Kyushu were seasoned combat veterans and well versed in combined operations — qualities that enhanced Marine Corps contributions to the complex occupation duties and relations with the U.S. Sixth Army. Major General Harry Schmidt commanded V Amphibious Corps. Schmidt was 59, a native of Holdrege, Nebraska, and a graduate of Nebraska State Normal College. He was commissioned in 1909 and in 1911 reported to Marine Barracks, Guam. Following a series of short tours in the Philippines and at state-side posts, he spent most of World War I on board ship. Interwar assignments included Quantico, Nicaragua, Headquarters Marine Corps, and China, where he served as Chief of Staff of the 2d Marine Brigade. Returning to Headquarters in 1938, Schmidt first served with the Paymaster's Department and then as assistant to the Commandant. In 1943, he assumed command of the 4th Marine Division which he led during the Roi Namur and Saipan Campaigns. Given the command of the V Amphibious Corps a year later, he led the unit during the assault and capture of Tinian and Iwo Jima. For his accomplishment during the campaigns, Schmidt received three Distinguished Service Medals. Ordered back to the United States following occupational duties in Japan, he assumed command of the Marine Training and Replacement Command, San Diego. General Schmidt died in 1968.

Major General LeRoy P. Hunt commanded the 2d Marine Division. Hunt was 53, a native of Newark, New Jersey, and a graduate of the University of California. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1917 and served with great distinction with the 5th Marines during World War I, receiving the Navy Cross and Distinguished Service Cross for repeated acts of heroism. Postwar assignments were varied, ranging from sea duty to commanding officer of the Western Mail Guard Detachment and work with the Work Projects Administration's Matanuska Colonization venture in Alaska. Following a short tour in Iceland, he was given command of the 5th Marines which he led in the seizure and defense of Guadalcanal. As the 2d Marine Division's assistant division commander he participated in mopping-up operations on Saipan and Tinian and in the Okinawa Campaign. Appointed division commander, he led the division in the occupation of Japan and for a period was Commanding General, I Army Corps. Returning to the United States, Hunt assumed duties as Commanding General, Department of Pacific and then Commanding General, FMFLant. General Hunt died in 1968.

Major General Thomas E. Bourke commanded the 5th Marine Division. Bourke was 49, a native of Robinson, Maryland, and a graduate of St. Johns College. He was commissioned in 1917 after service in the Maryland National Guard along the Mexican border. While enroute to Santo Domingo for his first tour, he and 50 recruits were diverted to St. Croix, becoming the first U. S. troops to land on what had just become the American Virgin Islands. Post-World War I tours included service at Quantico, Parris Island, San Diego, and Headquarters Marine Corps. He also served at Pearl Harbor; was commanding officer of the Legation Guard in Managua, Nicaragua; saw sea duty on board the battleship West Virginia (BB 48); and commanded the 10th Marines. Following the Guadalcanal and Tarawa campaigns, General Bourke was assigned as the V Amphibious Corps artillery officer for the invasion of Saipan. He next trained combined Army-Marine artillery units for the XXIV Army Corps, then preparing for the Leyte operation. With Leyte secured, he assumed command of the 5th Marine Division which was planning for the invasion of Japan. After the war's sudden end, the division landed at Sasebo, Kyushu, and assumed occupation duties. With disbandment of the 5th Marine Division, General Bourke became Deputy Commander and Inspector General of FMFPac. General Bourke died in 1978.

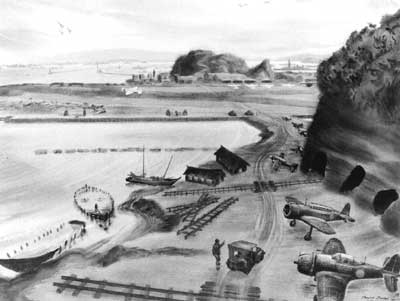

The continued cooperation of the Japanese with occupation directives and the lack of any overt signs of resistance also lessened the need for the fighter squadrons of MAG-31. Personnel and unit reductions similar to those experienced by the 4th Marines also affected the Marine air group. By the spring of 1946, reduced in strength and relieved of all routine surveillance missions by the Fifth Bomber Command, MAG-31, in early May, received orders to return as a unit to the United States. Prior to being released of all flight duties, the group performed one final task. Largely due to an extended period of inclement weather and poor sanitary conditions, the Yokosuka area had become infested with large black flies, mosquitoes, and fleas, causing the outbreak and spread of communicable diseases. Alarmed that service personnel might be affected, accessible areas were dusted with DDT by jeeps equipped with dusting attachments. The spraying effort was effective except in the city's alleys and surrounding narrow valleys, occupied by small houses and innumerable cesspools. "Fortunately we had a solution," wrote Captain Decker. MAG-31 was asked to tackle the job. "Daily, these young, daring flyers would zoom up the hills following the pathways, dusting with DDT. The children loved to run out in the open, throw wide their jackets, and become hidden momentarily in the clouds of DDT. It was fun for them and it helped us in delousing the city." On 18 June, with the final destruction of all but two of the seven wind tunnels at the Japanese First Technical Air Depot and the preparation of equipment for shipment, loading began. Earlier, the group's serviceable air craft were either flown to Okinawa, distributed to various Navy and Marine Corps activities in Japan, or shipped to Guam on the carrier Point Cruz (CVE 119). Prior to being hoisted on board, the planes made the shore to ship movement by Japanese barge equipped with a crane and operated by a Japanese crew. It was reported with amazement that "not a single plane was scratched." A small number of obsolete planes were stricken and their parts salvaged. On 20 June, the 737 remaining officers and men of MAG-31, led by Lieutenant Colonel John P. Condon, boarded the attack transport San Saba (APA-232) and sailed for San Diego. The departure of MAG-31 marked the end of Marine occupation activities in northern Japan.

|