| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

CLOSING IN: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) D-Day Weather conditions around Iwo Jima on D-day morning, 19 February 1945, were almost ideal. At 0645 Admiral Turner signalled "Land the landing force!" Shore bombardment ships did not hesitate to engage the enemy island at near point-blank range. Battleships and cruisers steamed as close as 2,000 yards to level their guns against island targets. Many of the "Old Battleships" had performed this dangerous mission in all theaters of the war. Marines came to recognize and appreciate their contributions. It seemed fitting that the old Nevada, raised from the muck and ruin of Pearl Harbor, should lead the bombardment force close ashore. Marines also admired the battleship Arkansas, built in 1912, and recently returned from the Atlantic where she had battered German positions at Point du Hoc at Normandy during the epic Allied landing on 6 June 1944.

Lieutenant Colonels Weller and William W. "Bucky" Buchanan, both artillery officers, had devised a modified form of the "rolling barrage" for use by the bombarding gunships against beachfront targets just before H-Hour. This concentration of naval gunfire would advance progressively as the troops landed, always re maining 400 yards to their front. Air spotters would help regulate the pace. Such an innovation appealed to the three division commanders, each having served in France during World War I. In those days, a good rolling barrage was often the only way to break a stalemate. The shelling was terrific. Admiral Hill would later boast that "there were no proper targets for shore bombardment remaining on Dog-Day morning." This proved to be an overstatement, yet no one could deny the unprecedented intensity of fire power Hill delivered against the areas surrounding the landing beaches. As General Kuribayashi would ruefully admit in an assessment report to Imperial General Headquarters, "we need to reconsider the power of bombardment from ships; the violence of the enemy's bombardments is far beyond description."

The amphibious task force appeared from over the horizon, the rails of the troopships crowded with combat-equipped Marines watching the spectacular fireworks. The Guadalcanal veterans among them realized a grim satisfaction watching American battleships leisurely pounding the island from just offshore. The war had come full cycle from the dark days of October 1942 when the 1st Marine Division and the Cactus Air Force endured similar shelling from Japanese battleships. The Marines and sailors were anxious to get their first glimpse of the objective. Correspondent John P. Marquand, the Pulitzer Prize winning writer, recorded his own first impressions of Iwo: "Its silhouette was like a sea monster, with the little dead volcano for the head, and the beach area for the neck, and all the rest of it, with its scrubby brown cliffs for the body." Lieutenant David N. Susskind, USNR, wrote down his initial thoughts from the bridge of the troopship Mellette: "Iwo Jima was a rude, ugly sight . . . . Only a geologist could look at it and not be repelled." As described in a subsequent letter home by Navy Lieutenant Michael F. Keleher, a surgeon in the 25th Marines:

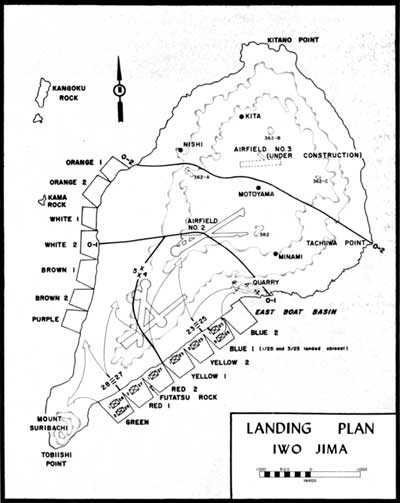

The commanders of the 4th and 5th Marine Divisions, Major Generals Clifton B. Cates and Keller E. Rockey, respectively, studied the island through binoculars from their respective ships. Each division would land two reinforced regiments abreast. From left to right, the beaches were designated Green, Red, Yellow, and Blue. The 5th Division would land the 28th Marines on the left flank, over Green Beach, the 27th Marines over Red. The 4th Division would land the 23d Marines over Yellow Beach and the 25th Marines over Blue Beach on the right flank. General Schmidt reviewed the latest intelligence reports with growing uneasiness and requested a reassignment of reserve forces with General Smith. The 3d Marine Division's 21st Marines would replace the 26th Marines as corps reserve, thus releasing the latter regiment to the 5th Division.

Schmidt's landing plan envisioned the 28th Marines cutting the island in half, then turning to capture Suribachi, while the 25th Marines would scale the Rock Quarry and then serve as the hinge for the entire corps to swing around to the north. The 23d Marines and 27th Marines would capture the first airfield and pivot north within their assigned zones. General Cates was already concerned about the right flank. Blue Beach Two lay directly under the observation and fire of suspected Japanese positions in the Rock Quarry, whose steep cliffs overshadowed the right flank like Suribachi dominated the left. The 4th Marine Division figured that the 25th Marines would have the hardest objective to take on D-day. Said Cates, "If I knew the name of the man on the extreme right of the right-hand squad I'd recommend him for a medal before we go in." The choreography of the landing continued to develop. Iwo Jima would represent the pinnacle of forcible amphibious assault against a heavily fortified shore, a complex art mastered painstakingly by the Fifth Fleet over many campaigns. Seventh Air Force Martin B-24 Liberator bombers flew in from the Marianas to strike the smoking island. Rocket ships moved in to saturate nearshore targets. Then it was time for the fighter and attack squadrons from Mitscher's Task Force 58 to contribute. The Navy pilots showed their skills at bombing and strafing, but the troops naturally cheered the most at the appearance of F4U Corsairs flown by Marine Fighter Squadrons 124 and 213 led by Lieutenant Colonel William A. Millington from the fleet carrier Essex. Colonel Vernon E. Megee, in his shipboard capacity as air officer for General Smith's Expeditionary Troops staff, had urged Millington to put on a special show for the troops in the assault waves. "Drag your bellies on the beach," he told Millington. The Marine fighters made an impressive approach parallel to the island, then virtually did Megee's bidding, streaking low over the beaches, strafing furiously. The geography of the Pacific War since Bougainville had kept many of the ground Marines separated from their own air support, which had been operating in areas other than where they had been fighting, most notably the Central Pacific. "It was the first time a lot of them had ever seen a Marine fighter plane," said Megee. The troops were not disappointed. The planes had barely disappeared when naval gunfire resumed, carpeting the beach areas with a building crescendo of high-explosive shells. The ship-to-shore movement was well underway, an easy 30-minute run for the tracked landing vehicles (LVTs). This time there were enough LVTs to do the job: 68 LVT(A)4 armored amtracs mounting snub-nosed 75mm cannon leading the way, followed by 380 troop-laden LVT 4s and LVT 2s. The waves crossed the line of departure on time and chugged confidently towards the smoking beaches, all the while under the climactic bombardment from the ships. Here there was no coral reef, no killer neap tides to be concerned with. The Navy and Marine frogmen had reported the approaches free of mines or tetrahedrons. There was no premature cessation of fire. The "rolling barrage" plan took effect. Hardly a vehicle was lost to the desultory enemy fire.

The massive assault waves hit the beach within two minutes of H-hour. A Japanese observer watching the drama unfold from a cave on the slopes of Suribachi reported, "At nine o'clock in the morning several hundred landing craft with amphibious tanks in the lead rushed ashore like an enormous tidal wave." Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Williams, executive officer of the 28th Marines, recalled that "the landing was a magnificent sight to see—two divisions landing abreast; you could see the whole show from the deck of a ship." To this point, so far, so good. The first obstacle came not from the Japanese but the beach and the parallel terraces. Iwo Jima was an emerging volcano; its steep beaches dropped off sharply, producing a narrow but violent surf zone. The soft black sand immobilized all wheeled vehicles and caused some of the tracked amphibians to belly down. The boat waves that closely followed the LVTs had more trouble. Ramps would drop, a truck or jeep would attempt to drive out, only to get stuck. In short order a succession of plunging waves hit the stalled craft before they could completely unload, filling their sterns with water and sand, broaching them broadside. The beach quickly resembled a salvage yard. The infantry, heavily laden, found its own "foot-mobility" severely restricted. In the words of Corporal Edward Hartman, a rifleman with the 4th Marine Division: "the sand was so soft it was like trying to run in loose coffee grounds." From the 28th Marines came this early, laconic report: "Resistance moderate, terrain awful." The rolling barrage and carefully executed landing produced the desired effect, suppressing direct enemy fire, providing enough shock and distraction to enable the first assault waves to clear the beach and begin advancing inward. Within minutes 6,000 Marines were ashore. Many became thwarted by increasing fire over the terraces or down from the highlands, but hundreds leapt forward to maintain assault momentum. The 28th Marines on the left flank had rehearsed on similar volcanic terrain on the island of Hawaii. Now, despite increasing casualties among their company commanders and the usual disorganization of landing, elements of the regiment used their initiative to strike across the narrow neck of the peninsula. The going became progressively costly as more and more Japanese strongpoints along the base of Suribachi seemed to spring to life. Within 90 minutes of the landing, however, elements of the 1st Battalion, 28th Marines, had reached the western shore, 700 yards across from Green Beach. Iwo Jima had been severed—"like cutting off a snake's head," in the words of one Marine. It would represent the deepest penetration of what was becoming a very long and costly day. The other three regiments experienced difficulty leaving the black sand terraces and wheeling across towards the first airfield. The terrain was an open bowl, a shooting gallery in full view from Suribachi on the left and the rising tableland to the right. Any thoughts of a "cakewalk" quickly vanished as well-directed machine-gun fire whistled across the open ground and mortar rounds began dropping along the terraces. Despite these difficulties, the 27th Marines made good initial gains, reaching the southern and western edges of the first airfield before noon. The 23d Marines landed over Yellow Beach and sustained the brunt of the first round of Japanese combined arms fire. These troops crossed the second terrace only to be confronted by two huge concrete pillboxes, still lethal despite all the pounding. Overcoming these positions proved costly in casualties and time. More fortified positions appeared in the broken ground beyond. Colonel Walter W. Wensinger's call for tank support could not be immediately honored because of trafficability and congestion problems on the beach. The regiment clawed its way several hundred yards towards the eastern edge of the airstrip.

|