| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

CLOSING IN: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) Assault Preparations (continued) The physical separation of the three divisions, from Guam to Hawaii, had no adverse effect on preparatory training. Where it counted most—the proficiency of small units in amphibious landings and combined-arms assaults on fortified positions—each division was well prepared for the forthcoming invasion. The 3d Marine Division had just completed its participation in the successful recapture of Guam; field training often extended to active combat patrols to root out die-hard Japanese survivors. In Maui, the 4th Marine Division prepared for its fourth major assault landing in 13 months with quiet confidence. Recalled Major Frederick J. Karch, operations officer for the 14th Marines, "we had a continuity there of veterans that was just unbeatable." In neighboring Hawaii, the 5th Marine Division calmly prepared for its first combat experience. The unit's newness would prove misleading. Well above half of the officers and men were veterans, including a number of former Marine parachutists and a few Raiders who had first fought in the Solomons. Lieutenant Colonel Donn J. Robertson took command of the 3d Battalion, 27th Marines, barely two weeks before embarkation and immediately ordered it into the field for a sustained live-firing exercise. Its competence and confidence impressed him. "These were professionals," he concluded.

Among the veterans preparing for Iwo Jima were two Medal of Honor recipients from the Guadalcanal campaign, Gunnery Sergeant John "Manila John" Basilone and Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Galer. Headquarters Marine Corps preferred to keep such distinguished veterans in the states for morale purposes, but both men wrangled their way back overseas—Basilone leading a machine gun platoon, Galer delivering a new radar unit for employment with the Landing Force Air Support Control Unit. The Guadalcanal veterans would only shake their heads at the abundance of amphibious shipping available for Operation Detachment. Admiral Turner would command 495 ships, of which fully 140 were amphibiously configured, the whole array 10 times the size of Guadalcanal's task force. Still there were problems. So many of the ships and crews were new that each rehearsal featured embarrassing collisions and other accidents. The new TD-18 bulldozers were found to be an inch too wide for the medium landing craft (LCMs). The newly modified M4A3 Sherman tanks proved so heavy that the LCMs rode with dangerously low freeboards. Likewise, 105mm howitzers overloaded the amphibious trucks (DUKWs) to the point of near unseaworthiness. These factors would prove costly in Iwo's unpredictable surf zone. These problems notwithstanding, the huge force embarked and began the familiar move to westward. Said Colonel Robert E. Hogaboom, Chief of Staff, 3d Marine Division, "we were in good shape, well trained, well equipped and thoroughly supported." On Iwo Jima, General Kuribayashi had benefitted from the American postponements of Operation Detachment because of delays in the Philippines campaign. He, too, felt as ready and prepared as possible. When the American armada sailed from the Marianas on 13 February, he was forewarned. He deployed one infantry battalion in the vicinity of the beaches and lower airfield, ordered the bulk of his garrison into its assigned fighting holes, and settled down to await the inevitable storm. Two contentious issues divided the Navy-Marine team as D-day at Iwo Jima loomed closer. The first involved Admiral Spruance's decision to detach Task Force 58, the fast carriers under Admiral Marc Mitscher, to attack strategic targets on Honshu simultaneously with the onset of Admiral Blandy's preliminary bombardment of Iwo. The Marines suspected Navy-Air Force rivalry at work here—most of Mitscher's targets were aircraft factories which the B-29s had missed badly a few days earlier. What the Marines really begrudged was Mitscher taking all eight Marine Corps fighter squadrons, assigned to the fast carriers, plus the new fast battleships with their 16-inch guns. Task Force 58 returned to Iwo in time to render sparkling support with these assets on D-day, but two days later it was off again, this time for good. The other issue was related and it concerned the continuing argument between senior Navy and Marine officers over the extent of preliminary naval gunfire. The Marines looked at the intelligence reports on Iwo and requested 10 days of preliminary fire. The Navy said it had neither the time nor the ammo to spare; three days would have to suffice. Holland Smith and Harry Schmidt continued to plead, finally offering to compromise to four days. Turner deferred to Spruance who ruled that three days prep fires, in conjunction with the daily pounding being administered by the Seventh Air Force, would do the job. Lieutenant Colonel Donald M. Weller, USMC, served as the FMFPAC/Task Force 51 naval gun fire officer, and no one in either sea service knew the business more thoroughly. Weller had absorbed the lessons of the Pacific War well, especially those of the conspicuous failures at Tarawa. The issue, he argued forcibly to Admiral Turner, was not the weight of shells nor their caliber but rather time. Destruction of heavily fortified enemy targets took deliberate, pinpoint firing from close ranges, assessed and adjusted by aerial observers. Iwo Jima's 700 "hard" targets would require time to knock out, a lot of time.

Neither Spruance nor Turner had time to give, for strategic, tactical, and logistical reasons. Three days of firing by Admiral Blandy's sizeable bombardment force would deliver four times the amount of shells Tarawa received, and one and a half times that delivered against larger Saipan. It would have to do.

In effect, Iwo's notorious foul weather, the imperviousness of many of the Japanese fortifications, and other distractions dissipated even the three days' bombardment. "We got about thirteen hours' worth of fire support during the thirty-four hours of available daylight," complained Brigadier General William W. Rogers, chief of staff to General Schmidt. The Americans received an unexpected bonus when General Kuribayashi committed his only known tactical error during the battle. This occurred on D-minus-2, as a force of 100 Navy and Marine underwater demolition team (UDT) frogmen bravely approached the eastern beaches escorted by a dozen LCI landing craft firing their guns and rockets. Kuribayashi evidently believed this to be the main landing and authorized the coastal batteries to open fire. The exchange was hot and heavy, with the LCIs getting the worst of it, but U.S. battleships and cruisers hurried in to blast the casemate guns suddenly revealed on the slopes of Suribachi and along the rock quarry on the right flank.

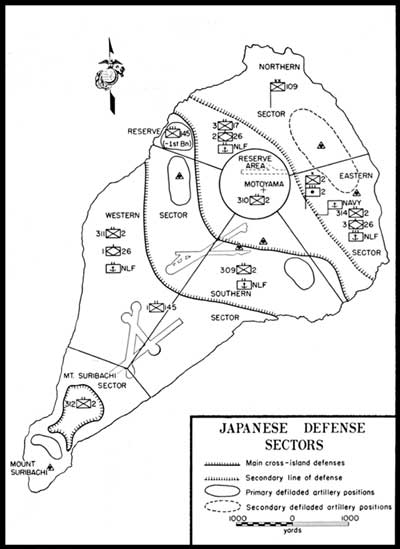

That night, gravely concerned about the hundreds of Japanese targets still untouched by two days of firing, Admiral Blandy conducted a "council of war" on board his flagship. At Weller's suggestion, Blandy junked the original plan and directed his gunships to concentrate exclusively on the beach areas. This was done with considerable effect on D minus-1 and D-day morning itself. Kuribayashi noted that most of the positions the Imperial Navy insisted on building along the beach approaches had in fact been destroyed, as he had predicted. Yet his main defensive belts criss-crossing the Motoyama Plateau remained intact. "I pray for a heroic fight," he told his staff. On board Admiral Turner's flagship, the press briefing held the night before D-day was uncommonly somber. General Holland Smith predicted heavy casualties, possibly as many as 15,000, which shocked all hands. A man clad in khakis without rank insignia then stood up to address the room. It was James V. Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy. "Iwo Jima, like Tarawa, leaves very little choice," he said quietly, "except to take it by force of arms, by character and courage."

|