| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

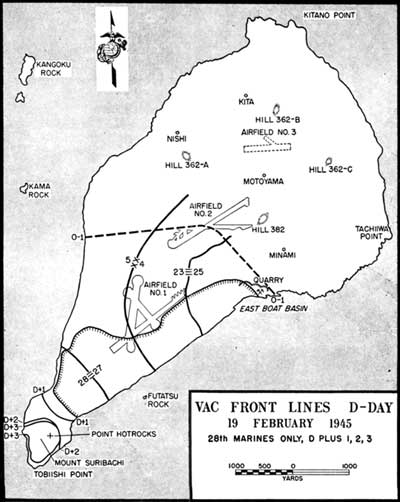

CLOSING IN: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) D-Day (continued) No assault units found it easy going to move inland, but the 25th Marines almost immediately ran into a buzz-saw trying to move across Blue Beach. General Cates had been right in his appraisal. "That right flank was a bitch if there ever was one," he would later say. Lieutenant Colonel Hollis W. Mustain's 1st Battalion, 25th Marines, managed to scratch forward 300 yards under heavy fire in the first half hour, but Lieutenant Colonel Chambers' 3d Battalion, 25th Marines, took the heaviest beating of the day on the extreme right trying to scale the cliffs leading to the Rock Quarry. Chambers landed 15 minutes after H-hour. "Crossing that second terrace," he recalled, "the fire from automatic weapons was coming from all over. You could've held up a cigarette and lit it on the stuff going by. I knew immediately we were in for one hell of a time."

This was simply the beginning. While the assault forces tried to overcome the infantry weapons of the local defenders, they were naturally blind to an almost imperceptible stirring taking place among the rocks and crevices of the interior highlands. With grim anticipation, General Kuribayashi's gunners began unmasking the big guns—the heavy artillery, giant mortars, rockets, and anti-tank weapons held under tightest discipline for this precise moment. Kuribayashi had patiently waited until the beaches were clogged with troops and material. Gun crews knew the range and deflection to each landing beach by heart; all weapons had been preregistered on these targets long ago. At Kuribayashi's signal, these hundreds of weapons began to open fire. It was shortly after 1000. The ensuing bombardment was as deadly and terrifying as any of the Marines had ever experienced. There was hardly any cover. Japanese artillery and mortar rounds blanketed every corner of the 3,000-yard-wide beach. Large-caliber coast defense guns and dual-purpose antiaircraft guns firing horizontally added a deadly scissors of direct fire from the high ground on both flanks. Marines stumbling over the terraces to escape the rain of projectiles encountered the same disciplined machine-gun fire and mine fields which had slowed the initial advance. Casualties mounted appallingly. Two Marine combat veterans observing this expressed a grudging admiration for the Japanese gunners. "It was one of the worst blood-lettings of the war," said Major Karch of the 14th Marines. "They rolled those artillery barrages up and down the beach—I just didn't see how anybody could live through such heavy fire barrages." Said Lieutenant Colonel Joseph L. Stewart, "The Japanese were superb artillerymen . . . . Somebody was getting hit every time they fired." At sea, Lieutenant Colonel Weller tried desperately to deliver naval gunfire against the Japanese gun positions shooting down at 3d Battalion, 25th Marines, from the Rock Quarry. It would take longer to coordinate this fire: the first Japanese barrages had wiped out the 3d Battalion, 25th Marines' entire Shore Fire Control Party.

As the Japanese firing reached a general crescendo, the four assault regiments issued dire reports to the flagship. Within a 10-minute period, these messages crackled over the command net:

The landing force suffered and bled but did not panic. The profusion of combat veterans throughout the rank and file of each regiment helped the rookies focus on the objective. Communications remained effective. Keen-eyed aerial observers spotted some of the now-exposed gun positions and directed naval gunfire effectively. Carrier planes screeched in low to drop napalm canisters. The heavy Japanese fire would continue to take an awful toll throughout the first day and night, but it would never again be so murderous as that first unholy hour. Marine Sherman tanks played hell getting into action on D-day. Later in the battle these combat vehicles would be the most valuable weapons on the battlefield for the Marines; this day was a nightmare. The assault divisions embarked many of their tanks on board medium landing ships (LSMs), sturdy little craft that could deliver five Shermans at a time. But it was tough disembarking them on Iwo's steep beaches. The stern anchors could not hold in the loose sand; bow cables run forward to "deadmen" LVTs parted under the strain. On one occasion the lead tank stalled at the top of the ramp, blocking the other vehicles and leaving the LSM at the mercy of the rising surf. Other tanks bogged down or threw tracks in the loose sand. Many of those that made it over the terraces were destroyed by huge horned mines or disabled by deadly accurate 47mm anti-tank fire from Suribachi. Other tankers kept coming. Their relative mobility, armored protection, and 75mm gunfire were most welcome to the infantry scattered among Iwo's lunar-looking, shell-pocked landscape. Both division commanders committed their reserves early. General Rockey called in the 26th Marines shortly after noon. General Cates ordered two battalions of the 24th Marines to land at 1400; the 3d Battalion, 24th Marines, followed several hours later. Many of the reserve battalions suffered heavier casualties crossing the beach than the assault units, a result of Kuribayashi's punishing bombardment from all points on the island.

Mindful of the likely Japanese counterattack in the night to come—and despite the fire and confusion along the beaches—both divisions also ordered their artillery regiments ashore. This process, frustrating and costly, took much of the afternoon. The wind and surf began to pick up as the day wore on, causing more than one low-riding DUKW to swamp with its precious 105mm howitzer cargo. Getting the guns ashore was one thing; getting them up off the sand was quite another. The 75mm pack howitzers fared better than the heavier 105s. Enough Marines could readily hustle them up over the terraces, albeit at great risk. The 105s seemed to have a mind of their own in the black sand. The effort to get each single weapon off the beach was a saga in its own right. Somehow, despite the fire and unforgiving terrain, both Colonel Louis G. DeHaven, commanding the 14th Marines, and Colonel James D. Waller, commanding the 13th Marines, managed to get batteries in place, registered, and rendering close fire support well before dark, a singular accomplishment.

Japanese fire and the plunging surf continued to make a shambles out of the beachhead. Late in the afternoon, Lieutenant Michael F. Keleher, USNR, the battalion surgeon, was ordered ashore to take over the 3d Battalion, 25th Marines aid station from its gravely wounded surgeon. Keleher, a veteran of three previous assault landings, was appalled by the carnage on Blue Beach as he approached: "Such a sight on that beach! Wrecked boats, bogged-down jeeps, tractors and tanks; burning vehicles; casualties scattered all over." On the left center of the action, leading his machine gun platoon in the 1st Battalion, 27th Marines' attack against the southern portion of the airfield, the legendary "Manila John" Basilone fell mortally wounded by a Japanese mortar shell, a loss keenly felt by all Marines on the island. Farther east, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Galer, the other Guadalcanal Medal of Honor Marine (and one of the Pacific War's earliest fighter aces), survived the afternoon's fusillade along the beaches and began reassembling his scattered radar unit in a deep shell hole near the base of Suribachi. Late in the afternoon, Lieutenant Colonel Donn J. Robertson led his 3d Battalion, 27th Marines, ashore over Blue Beach, disturbed at the intensity of fire still being directed on the reserve forces this late on D-day. "They were really ready for us," he recalled. He watched with pride and wonderment as his Marines landed under fire, took casualties, stumbled forward to clear the beach. "What impels a young guy landing on a beach in the face of fire?" he asked himself. Then it was Robertson's turn. His boat hit the beach too hard; the ramp wouldn't drop. Robertson and his command group had to roll over the gunwales into the churning surf and crawl ashore, an inauspicious start.

The bitter battle to capture the Rock Quarry cliffs on the right flank raged all day. The beachhead remained completely vulnerable to enemy direct-fire weapons from these heights; the Marines had to storm them before many more troops or supplies could be landed. In the end, it was the strength of character of Captain James Headley and Lieutenant Colonel "Jumping Joe" Chambers who led the survivors of the 3d Battalion, 25th Marines, onto the top of the cliffs. The battalion paid an exorbitant price for this achievement, losing 22 officers and 500 troops by nightfall. The two assistant division commanders, Brigadier Generals Franklin A. Hart and Leo D. Hermle, of the 4th and 5th Marine Divisions respectively, spent much of D-day on board the control vessels marking both ends of the Line of Departure, 4,000 yards off shore. This reflected yet another lesson in amphibious techniques learned from Tarawa. Having senior officers that close to the ship-to-shore movement provided landing force decision-making from the most forward vantage point. By dusk General Hermle opted to come ashore. At Tarawa he had spent the night of D-day essentially out of contact at the fire-swept pier-head. This time he intended to be on the ground. Hermle had the larger operational picture in mind, knowing the corps commander's desire to force the reserves and artillery units on shore despite the carnage in order to build credible combat power. Hermle knew that whatever the night might bring, the Americans now had more troops on the island than Kuribayashi could ever muster. His presence helped his division forget about the day's disasters and focus on preparations for the expected counterattacks.

Japanese artillery and mortar fire continued to rake the beachhead. The enormous spigot mortar shells (called "flying ashcans" by the troops) and rocket-boosted aerial bombs were particularly scary—loud, whistling projectiles, tumbling end over end. Many sailed completely over the island; those that hit along the beaches or the south runways invariably caused dozens of casualties with each impact. Few Marines could dig a proper foxhole in the granular sand ("like trying to dig a hole in a barrel of wheat"). Among urgent calls to the control ship for plasma, stretchers, and mortar shells came repeated cries for sand bags. Veteran Marine combat correspondent Lieutenant Cyril P. Zurlinden, soon to become a casualty himself, described that first night ashore:

Personnel accounting was a nightmare under those conditions, but the assault divisions eventually reported the combined loss of 2,420 men to General Schmidt (501 killed, 1,755 wounded, 47 dead of wounds, 18 missing, and 99 combat fatigue). These were sobering statistics, but Schmidt now had 30,000 Marines ashore. The casualty rate of eight percent left the landing force in relatively better condition than at the first days at Tarawa or Saipan. The miracle was that the casualties had not been twice as high. General Kuribayashi had possibly waited a little too long to open up with his big guns. The first night on Iwo was ghostly. Sulfuric mists spiraled out of the earth. The Marines, used to the tropics, shivered in the cold, waiting for Kuribayashi's warriors to come screaming down from the hills. They would learn that this Japanese commander was different. There would be no wasteful, vainglorious Banzai attack, this night or any other. Instead, small teams of infiltrators, which Kuribayashi termed "Prowling Wolves," probed the lines, gathering intelligence. A barge-full of Japanese Special Landing Forces tried a small counterlanding on the western beaches and died to the man under the alert guns of the 28th Marines and its supporting LVT crews. Otherwise the night was one of continuing waves of indirect fire from the highlands. One high velocity round landed directly in the hole occupied by the 1st Battalion, 23d Marines' commander, Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Haas, killing him instantly. The Marines took casualties throughout the night. But with the first streaks of dawn, the veteran landing force stirred. Five infantry regiments looked north; a sixth turned to the business at hand in the south: Mount Suribachi.

|