| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

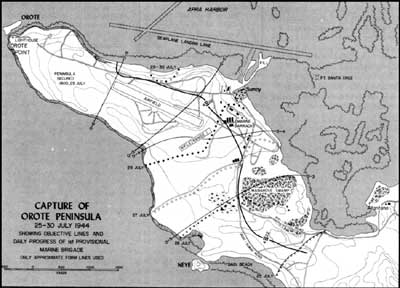

LIBERATION: Marines in the Recapture of Guam by Cyril J. O'Brien Orote The 22d Marines had driven up the coast from Agat in a series of hard-fought clashes with stubborn enemy defenders. The 4th Marines had swept up the slopes of Mount Alifan and secured the high ground overlooking the beachhead. By the 25th, the brigade was in line across the mouth of Orote Peninsula facing a formidable defensive line in depth, anchored in swamps and low hillocks, concealed by heavy undergrowth, and bristling with automatic weapons.

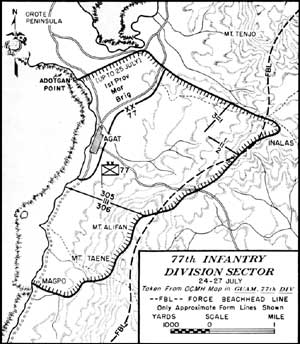

The 77th Infantry Division had taken over the rest of the southern beachhead, relieving the 4th Marines of its patrolling duties to the south and in the hills to the east. The division's artillery and a good part of the III Corps' big guns hammered the Japanese on Orote without letup. Just in case of enemy air attack, the beach defenses from Agat to Bangi Point were manned by the 9th Defense Battalion. There were not too many Japanese planes in the sky, and so the antiaircraft artillerymen could concentrate on firing across the water into the southern flank of the enemy's Orote positions. On Cabras Island, the 14th Defense Battalion moved into position where it could equally provide direct flanking fire on the peninsula's northern coast and stand ready to elevate its guns to fire at enemy planes in the skies above. The 5,000 Japanese defenders on Orote took part in General Takashina's all-out counterattack and it began in the early morning hours of 26 July. The attackers stormed vigorously out of the concealing mangrove swamp and the response was just as spirited. Here, as in the north, there was evidence that some of the attackers had fortified themselves with sake and there were senseless actions by officers who attacked the Marine tanks armed only with their samurai swords. There were deadly and professional attacks as well, with Marines bayoneted in their foxholes. There was one attendant communications breakdown obliging Captain Robert Frank, commanding officer of Company L, 22d Marines, to remain on the front relaying artillery spots to the regimental S-2 and thence to brigade artillery.

The artillery response was intense and effective. The fire was "drawn in closer and closer toward our front lines; 26,000 shells were thrown into the pocket [of attackers ] between midnight and 3 a.m." The screaming attacks came at 1230, then again at 0130, and at 0300. At daylight the muddy ground in front of the Marine positions was slick with blood. More than 400 Japanese bodies were sprawled in the driving rain. General Shepherd, secure in the knowledge that his frontline troops, 4th Marines on the left, 22d Marines on the right, had withstood the night's banzai attacks in good order, directed an attack to be launched at 0730. But first there would be another artillery preparation. At daybreak it opened with the 77th Infantry Division's 105s and 155s, the brigade's 75s, the defense battalions 90s, and whatever guns the 12th Marines could spare. It was one of the more intense preparations of the campaign. Major Charles L. Davis, S-3 of 77th Division Artillery, recalled how, on the request of General Shepherd, he had turned the heavy 155mm battalion and two 105mm battalions around to face Orote to soften the Japanese positions. The 155s and 105s battered well-prepared positions, and ripped the covering, protection, and camouflage from bunkers and trenches. Pieces of men soon hung in trees. Marines saw that this fire counted and made it a point to return to congratulate and thank the 77th's artillery section leaders.

The advance, when it came, only went 100 yards before it was addressed by a blistering front of machine gun and small arms fire. Enemy artillery fire came falling almost simultaneously with the cessation of American support, leaving the Marines to think the fire was from their own guns, a favorite Japanese ruse. For a moment there, the Japanese return fire on the 22d Marines disorganized its forward move. It was about 0815 before the attack was on again in full force, spearheaded by Marine and Army tanks. Immediately to the front of the 22d Marines was the infernal mangrove swamp from where the banzai attack had been mounted the night before. It was still manned heavily by Japanese, was dense, and the only means of penetrating it was by a 200-yard-long corridor along the regimental boundary which was covered by Japanese enfilade fire and could only be navigated with the cover of tanks. The armor gunners and commanders directed their fire just over the head of prone Marines and into the gunports of enemy pillboxes. By 1245, Colonel Schneider's regiment had worked its way through all bottlenecks past the mangrove swamps, destroying bunkers with demolitions and flamethrowers. The 4th's assault battalions kept pace with this advance, finding somewhat easier terrain but just as determined defenders. By evening the brigade had advanced 1,500 yards from its jump-off line. Both regiments, weary, wary, and waiting, dug in with an all-around defense. Again, there was a heavy pre-attack barrage on the 27th and the Marines were stopped again before they'd gone 100 yards. The 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, facing a well-defended ridge, a coconut grove, and a sinister clearing, was nearing the sentimental and tactically important goals of the old Marine barracks, its rifle range, and the runways of Orote airfield. With heavy tank support, the 22d Marines surged forward past the initial obstacles and by afternoon had reached positions well beyond the morning's battles. On the left of the 4th Marines, where resistance was lighter, the assault was led by tanks that beat down the brush. While inspecting positions there, Lieutenant Colonel Samuel D. Puller, the 4th's executive officer and brother of famed Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. "Chesty" Puller, was killed by a sniper. By mid-afternoon, the 4th Marines' assault elements broke out of the grove just short of the rifle range, only to stall in a new complex at dug-in defenses and minefields. Strangely, and yet not unusual in the climax of a losing engagement, a Japanese officer emerged to brandish his sword at a tank. It was easier than ritual suicide.

The horror of the American guns again must have been too much for the Japanese defending the immediate front. Surprisingly, they just cut and ran from their strong, well-defended positions. The elated Marines, who did not care why the enemy ran—just that they ran—now dug in only 300 yards from the prized targets. Their capture would wait for tomorrow, 28 July. The Japanese were now squeezed into the last quadrant of the peninsula. All of their strongly entrenched defenses had failed to hold. The Orote airfield, the old Marine barracks, the old parade ground which had not felt an American boot since 10 December 1941, were all about to be retrieved. General Shepherd sounded a great reveille on 28 July for what was left of the Japanese naval defenders: a 45-minute air strike and a 30-minute naval gunfire bombardment, joined by whatever guns the 77th Division, brigade, and antiaircraft battalions could muster. At 0830 the brigade would attack for Orote airfield.

Colonel Schneider's 22d Marines would take the barracks and Sumay and Colonel Shapley's 4th Marines would take the airfield and the rifle range. Japanese artillery and mortar fire had diminished, but small arms and machine guns still spoke intensely when the Marines attacked. At this bitter end, the Japanese were evoking a last-ditch stubbornness. American tanks were called up but most had problems with visibility and control. Wherever the thick scrub brush concealed the enemy, Major John S. Messers' 2d Battalion, 4th Marines called for increased tank support when one of his companies began taking heavy casualties. In response to General Shepherd's request, General Bruce sent forward a platoon of Army tank destroyers and a platoon of light tanks to beef up the attack. General Shepherd wanted the battle over now. He ordered a massive infantry and tank attack which kicked off at 1530 on the 28th. The Japanese did not intend to oblige this time by quitting; this was do or die. By nightfall all objectives were in plain sight, but there were still a few hundred yards to be gained. The Marines stood fast for the night, hoping the Japanese would sacrifice themselves in counterattack, but no such luck occurred. When the attack resumed on the 29th, after the usual Army and Marine artillery preparation and an awesomely heavy air strike, Army and Marine tanks led the way onto the airfield. Resistance was meager. By early afternoon, the airfield was secured and the 22d Marines had occupied what was left of the old Marine barracks. A bronze plaque, which had long been mounted at the entrance to the barracks, was recovered and held for reinstallation at a future date. The Japanese found this latest advance difficult to accept. Suicides were many and random. Soldiers jumped off cliffs, hugged exploding grenades, even cut their own throats. Private First Class George F. Eftang, with the 4th Marines' supporting pack howitzer battalion, saw the suicides: "I could see the Japanese jumping to their deaths. I actually felt sorry for them. I knew they had families and sweethearts like anyone else." While the embattled peninsula still swarmed with patrols, Admiral Spruance; Generals Smith, Geiger, Larsen (the future island commander), and Shepherd; Colonels Shapley and Schneider, and others who could be spared, arrived for a ceremonial flag raising and heartfelt tribute to an old barracks and those Marines who had made it home. General Shepherd called it hallowed ground and told the distinguished assemblage, which included a hastily cleaned-up honor guard of brigade troops: "you have avenged the loss of our comrades who were overcome by a numerically superior force three days after Pearl Harbor. Under our flag this island again stands ready to fulfill its destiny as an American fortress in the Pacific." Many of the Marines standing at attention, watching the historic ceremony, could only thank God that they were still alive. At the end of this ceremony, engineers moved onto the airfield to clear away debris and fill the many shell and bomb holes. Only six hours after the first bulldozer clanked onto the runways, a Navy torpedo bomber made an emergency landing. Soon the light artillery spotting planes were regularly flying from them. The capture of Orote Peninsula had cost the brigade 115 men killed, 721 wounded, and 38 missing in action. The enemy toll of counted dead was 1,633. It was obvious that on Orote as at Fonte, there were many Japanese still unaccounted for and presumably ready still to fight to prevent the island's capture.

|