| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

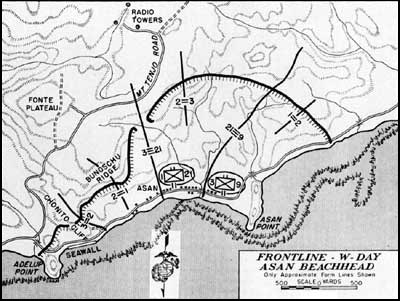

LIBERATION: Marines in the Recapture of Guam by Cyril J. O'Brien The Southern Beaches In the south at Agat, despite favorable terrain for the attack, the 1st Brigade found enemy resistance at the beachhead to be more intense than that which the 3d Division found on the northern beaches. Small arms and machine gun fire, and the incessant fires of two 75mm guns and a 37mm gun from a concrete blockhouse with a four-foot thick roof built into the nose of Gaan Point, greeted the invading Marines as the LVTs churned ashore. The structure had been well camouflaged and not spotted by photo interpreters before the landing nor, unfortunately, selected as a target for bombing. As a result, its guns knocked out two dozen amtracs carrying elements of the 22d Marines. For the assault forces' first hours ashore on W-Day on the southern beaches, the Gaan position posed a major problem. The assault at Agat was treated to the same thunderous naval gunfire support which had disrupted and shook the ground in advance of the landings on the northern beaches at Asan. When the 1st Brigade assault wave was 1,000 yards from the beach, hundreds of 4.5-inch rockets from LCI(G)s (Landing Craft, Infantry, Gunboat) slammed into the strand. It would be the last of the powerful support the troops of the brigade in assault would get before they touched down on Guam.

While the LVTs, the DUKWs (amphibious trucks), and the LCVPs were considerably off shore, there was virtually no enemy fire from the beach. An artillery observation plane reported no observed enemy fire. The defenders at Agat, however, 1st and 2d Battalions, 38th Infantry, would respond in their own time. The loss of so many amtracs as the assault waves neared the beaches meant that, later in the day, there would not be enough LVTs for the transfer of all supplies and men from boats to amtracs at the Agat reef. This shortage of tractors would plague the brigade until well after W-Day. The damage caused to assault and cargo craft on the reef, and the precision of Japanese guns became real concerns to General Shepherd. Some of the Marines and most of the soldiers who came in after the first assault waves would wade ashore with full packs, water to the waist or higher, facing the perils of both underwater shellholes and Japanese fire. Fortunately, by the time the bulk of the 77th Division waded in, these twin threats were not as great because the Marines ashore were spread out and keeping the Japanese occupied. The Japanese Agat command had prepared its defenses well with thick-walled bunkers and smaller pillboxes. The 75mm guns on Gaan Point were in the middle of the landing beaches. Crossfire from Gaan coordinated with the machine guns on nearby tiny Yona island to rake the beaches allocated to the 4th Marines under Lieutenant Colonel Alan Shapley. The 4th Marines was to establish its beachhead, and protect the right or southernmost flank. After bitter fighting, the 4th Marines forged ahead on the low ground to its front and cleared Bangi Point where bunker walls could withstand a round from a battleship. Lieutenant Colonel Shapley set up a block on what was to be known as Harmon Road leading down from the mountains to Agat. A lesson well learned in previous operations was that the Japanese would be back in strength and at night.

When the Marines landed, they found an excellent but undermanned Japanese trench system on the beaches, and while the pre-landing bombardment had driven enemy defenders back into their holes, they nonetheless were able to pour heavy machine gun and mortar fire down on the invaders. Pre-landing planning called for the Marine amtracs to drive 1,000 yards inland before discharging their embarked Marines, but this tactic failed because of a heavily mined beachhead, with its antitank ditches and other obstacles. However, the brigade attack ashore was so heavy, with overwhelming force the Marines were able to break through, and by 1034, the assault forces were 1,000 yards inland, and the 4th Marines' reserve battalion had landed. After receiving extremely heavy fire from all emplaced Japanese forces, the Marines worked on cleaning out bypassed bunkers together with the now-landed tanks. By 1330, the Gaan Point blockhouse had been eliminated by taking the position from the rear and blasting the surprised enemy gunners before they could offer effective resistance. At this time also, the brigade command group was on the beach and General Shepherd had opened his command post. The 22d Marines, led by Colonel Merlin F. Schneider, was battered by a hail of small arms and mortar fire on hitting its assigned beach, and suffered heavy losses of men and equipment in the first minutes. Private First Class William L. Dunlap could vouch for the high casualties. The dead, Dunlap recalled, included the battalion's beloved chaplain, who had been entrusted with just about everybody's gambling money "to hold for safekeeping," the Marines never for a minute considering that he was just as mortal as they. The 1st Battalion, 22d Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Walfried H. Fromhold), had left its section of the landing zone and moved to the shattered town of Agat, after which the battalion would drive north and eventually seal off heavily defended Orote Peninsula, shortly to be the scene of a major battle.

The 22d Marines' 2d Battalion, (Lieutenant Colonel Donn C. Hart), in the center of the beachhead, quickly and easily moved 1,000 yards directly ahead inland from the beach. The battalion could have gone on to one of the W-Day goals, the local heights of Mount Alifan, if American bombs had not fallen short, halting the attack. The 1st Battalion moved into the ruins of Agat and at 1020 was able to say, "We have Agat," although there was still small arms resistance in the rubble. By 1130 the battalion was also out to Harmon Road, which led to the northern shoulder of Mount Alifan. Even as Fromhold's men made their advances, Japanese shells hit the battalion aid station, wounding and killing members of the medical team and destroying supplies. Not until later that afternoon was the 1st Battalion sent another doctor.

On the right of the landing waves, Major Bernard W. Green's 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, ran head-on into a particularly critical hill mass (Hill 40) near Bangi Point, which had been thoroughly worked over by the Navy. Hill 40's unexpectedly heated defense indicated that the Japanese recognized its importance, commanding the beaches where troops and supplies were coming ashore. It took tanks and the support of the 3d Battalion to claim the position. Before dark on W-Day, the 2d Battalion, 22d Marines, could see the 4th Marines across a deep gully. The latter held a thin, twisted line extending 1,600 yards from the beach to Harmon Road. The 22d Marines held the rest of a beachhead 4,500 yards long and 2,000 yards deep. At nightfall of W-Day, General Shepherd summed up to General Geiger: "Own casualties about 350. Enemy unknown. Critical shortages of fuel and ammunition all types. Think we can handle it. Will continue as planned tomorrow." Helping to ensure that the Marines would stay on shore once they landed was a host of unheralded support troops who had been struggling since daylight to manage the flow of vital supplies to the beaches. Now, as W-Day's darkness approached, the 4th Ammunition Company, a black Marine unit, guarded the brigade's ammunition depot ashore. During their sleepless night, these Marines killed 14 demolition-laden infiltrators approaching the dump. Faulty communications delayed the order to land the Army's 305th Regimental Combat Team (Colonel Vincent J. Tanzola), elements of the assault force, for hours. Slated for a morning landing, the 2d Battalion of Lieutenant Colonel Robert D. Adair did not get ashore until well after nightfall. As no amtracs were then available, the soldiers had to walk in from the reef. Some soldiers slipped under water into shellholes and had to swim for their lives in a full tide. The rest of the 305th had arrived on the beach, all wet, some seasick, by 0600 on W plus-1.

|