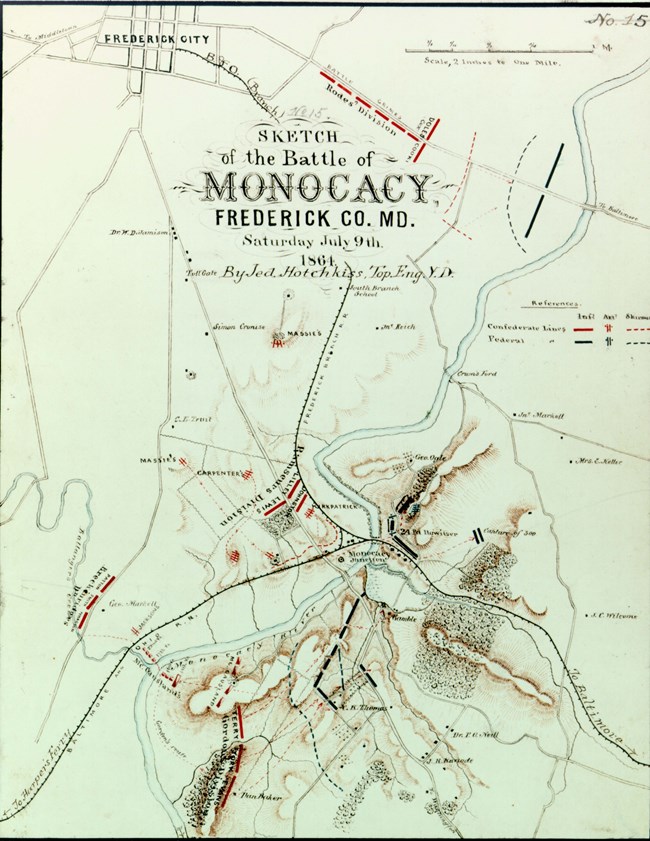

The Battle of Monocacy began around 8:30 a.m. when Confederate skirmishers, commanded by General Stephen Ramseur, advanced south along the Georgetown Pike and encountered Union infantry near Monocacy Junction. Wallace placed troops north of Monocacy Junction and a wooden covered bridge that carried the pike over the Monocacy River, blocking Early’s best route to Washington. Ramseur’s division continued to pressure Union forces near Monocacy Junction throughout the day, but they were unable to drive back the Union defense, composed of troops from Maryland and Vermont. After encountering resistance near Monocacy Junction, Confederates looked for another way to cross the river. Confederate General John McCausland’s cavalrymen found the Worthington Ford almost a mile downriver of the wooden covered bridge, and by 10:30 a.m. had begun to cross, placing pressure on Wallace’s forces south of the river. When Wallace learned of the Confederate presence south of the Monocacy, he ordered the wooden covered bridge burned to protect his new right flank as he shifted his main battle lines to the west onto the Thomas Farm. The first Confederate attack south of the Monocacy began around 11:00 a.m., as McCausland’s men advanced east and encountered Federal infantry from Union General James Ricketts’s Sixth Corps division. McCausland was repulsed, and formed for another attack around 2:00 p.m., moving from the Worthington Farm toward the Thomas House. While the Confederates gained control of the Thomas Farm, they were soon pushed back by Federal forces in a savage counter attack. In the midst of McCausland’s second cavalry attack, help was on the way for the Confederates. Confederate General John B. Gordon’s division forded the Monocacy River using the Worthington Ford and by mid-afternoon was ready to attack. Near 3:30 p.m. Gordon’s three brigades swept forward en echelon from right, moving from Brooks Hill toward the Union line on the Thomas Farm. The fighting was fierce, with heavy casualties falling on both sides. The Union battle line began to waver and then fell back toward the Georgetown Pike. Confederates where able to threaten and eventually turn the Union right flank, Wallace had no choice but to retreat from the field to save his remaining men. By 5:00 p.m., the Federals were in full retreat to the east, and Confederates would take the field. During the fighting roughly 2,200 men had been killed, wounded, captured, or were listed as missing (900 Confederate, 1,300 Federal). While the Confederates had won the Battle of Monocacy, Lew Wallace was ultimately successful. His efforts had delayed Jubal Early’s advance long enough for additional Union reinforcements to reach Washington D.C. By the time Early’s men reached the capital on July 11, help had arrived in the Federal capital. Some fighting and skirmishing occurred near Fort Stevens on the city’s outskirts, but Early was unable to take Washington. Early and his men withdrew back into Maryland and eventually crossed the Potomac River back into Virginia. Their campaign was over. Monocacy was not one of the largest battles of the Civil War, but it had an impact much larger than many know. Early had successfully reached Washington, forcing Grant to send reinforcements northward, but his campaign was ultimately foiled by the delaying tactics of Lew Wallace and his men at Monocacy on July 9. Because of this, the Battle of Monocacy has forever been known as “The Battle That Saved Washington.” |

Last updated: May 28, 2020