NPS photo On this page, Park Ranger Roger Fuller addresses the most frequently asked questions about the British soldier of 1775.A man, at least 17 years of age, who volunteered to join a full-time, professional army. According to the law, women could not join the military. The men who joined had to be of sound body and mind. In most cases, he had to be a British subject, and not Catholic.

He was somebody, often with a family to feed, who had probably lost his skilled job as a weaver, farmer, tailor or spinner during Britain’s many economic crises in the 18th century. He might also have been a young man who was trying to escape a boring life of drudgery on a farm or in the city. Indeed, many joined, leaving working occupations, just to get a change in their lives.

He might have come from anywhere in the British Isles. British army regiments recruited from all over the nation and sometimes even in its colonies. In 1775, however, most soldiers were English. The officers, however, enjoyed a bare majority of Scots and Irish.

He joined the army by meeting a recruiting party coming through his town or at a job fair. He was sworn in by the officer of the recruiting party in the presence of a magistrate, and given a bounty of money, most of which would be consumed by paying for his uniform and other necessary items.

Not usually. There is a myth about all British soldiers being criminals who were forced to join the army. The reality was that few judges made criminals join the army, since criminals make bad soldiers. Great Britain had tried “pressing” men, as in a draft, but it had failed to produce enough recruits and had proved enormously unpopular. Most soldiers joined the army willingly. Yet there was still some forced enlistment, in many cases as a result of trickery or impressment by unscrupulous recruiting parties who were trying to fulfill their recruiting quotas.

As long as the King wanted him to serve! This could be anywhere from three years to the duration of the war, or for his entire life. It depended on circumstances.

Again, it depended on circumstances. By law, the regiment (the group of 477 men the recruit joined) could have up to six wives “on the strength” of the regiment to serve as cleaning, mending and nursing help. However, the reality was, especially if the regiment had a generous and thoughtful colonel in charge of it, there would often be many times that number to perform all the various chores that military life demanded, as well as to keep the men happy. This also meant that many children lived with the regiment, too. These children, as did their mothers, would be given food and wages by the army to perform many other menial but necessary tasks, such as sewing, mending, and cleaning out latrines and horse stalls. Usually, the men did the cooking for each other.

Not as soldiers carrying muskets, but male children could become musicians playing the fife, drum or bugle from an early age, sometimes as young as ten or eleven. They would carry on until adulthood, since musicians were valuable for playing music that encouraged the troops as well as signaled to them when they marched or fought.

The British redcoat private earned eight pence a day. If he were a corporal or sergeant, that is, enlisted men who oversaw other enlisted men, they could earn more, as much as a shilling or more (twelve pence). Eight pence a day was not a great deal of money. It was less than what an unskilled laborer earned, hence not many laborers joined the army. Usually the unemployed skilled workers joined the army, because they had no other way to make a living and would have had to compete for the few available laborer jobs.

Not much. Over half of a soldier’s eight pence a day pay would go towards paying for the cost of his uniform, food, shoes, etc., as well as for his medical care, chaplain, and old age pension. The rest would go for incidental expenses such as ale, tobacco, washing and mending, etc.

In peacetime, there were few forts and castles available for soldiers to use as housing, so most soldiers, both officers and men alike, were quartered in taverns, rooming houses and private homes. “Quartering” meant that the government told you, the owner of the house, that you had to house and feed soldiers, whether you liked it or not. However, to make up for having strangers living in your house, the government paid you very well for it. On campaign, that is, during wartime, soldiers on the march lived in tents, sometimes four six men in a six foot by seven-foot tent, including wives and children, too.

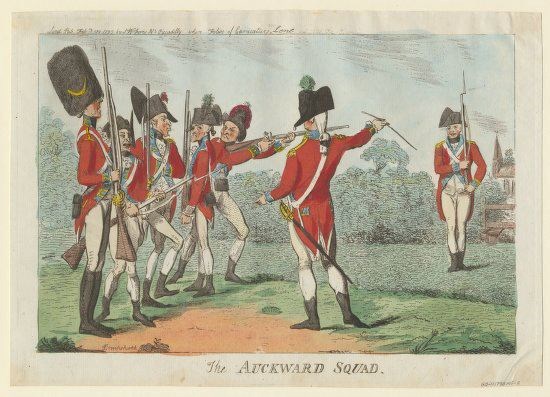

The new soldier or recruit would be assigned to a group of other new men. Under the watchful eye of an officer, a sergeant would train them how to stand, act and obey like a soldier by constant repetition until the men knew how to do it without thinking. The soldier would be taught then how to march by himself, then how to march with other men in groups, and then how to handle and shoot the musket. He would also be trained how to move about on the battlefield, and how to shoot his musket together with other men at the same time. This way of shooting is called “volley fire”. It was the best way to win on the battlefield back then. When the recruits learned their job well enough, they were assigned to different regiments, and completed their training there.

On average, it took about eighteen months. There was great deal one had to learn, and one learned most of it on the job. A soldier had to learn how to do everything from care of his uniform and equipment, to marching, to shooting, to how to stand guard, and how to fight. Some soldiers such as the light infantry, pioneers and grenadiers, knew even more because they had special duties.

The “regiment” is very important to know about if you want to understand the British Redcoat. It was the basic grouping of a complete army unit. The British Army in 1775 was composed of seventy regiments, all denoted by numerical order in status, seniority and privileges granted to them. The most senior regiment of the army was the 1st Regiment of Foot, the Royal Regiment, the oldest regiment in the army. Yet, all regiments, no matter what their number, could compete for privileges from, and gain favor with, the King. This led to great rivalries among Army regiments. A regiment, according to law, was supposed to be 477 men. It was composed of ten companies of men, about 47 men in each. The regiment was run by a colonel and his officers.It was a very tightly knit, protective group that more often resembled a very large family in its character, history, traditions, and habits. As a result, the regiments would be very different in personality from one another, much like sports teams today are quite different from each other. Sports teams have sometimes bitter rivalries today, as did regiments in armies back then. Men in their regiments trusted each other. Together, through their common experiences as soldiers, they felt bound to each other as friends and family. Such men would do their best not to let their comrades down in battle and would stick up for each other when men from other regiments or civilians (non-soldiers) insulted or attacked them. Men would fight and die for their regiment and its colours, rather than be cowards. Cowardice dishonored their regiment and stained its reputation in the army.

“The colours” are the regimental flags which are carried and flown whenever the army marches or goes to battle. Each regiment had two distinctive and bright flags. The first would be the particular flag which denoted the regiment and the second would be the national flag, with the regimental number on it. Both would have been touched by the King himself at the flags’ dedications. These flags were guarded day and night. In the smoke and confusion of the battlefield they were a necessary rallying point for soldiers. They had to be protected at the cost of one’s own life, since capturing enemy colours was a huge prize that brought fame and advancement to the winners, but dishonor and utter hate for those who allowed the enemy to capture them. Your name would go down in history as the “man who lost the colours”.

Not officially, but colonels, who were often rich men, sometimes paid for extra food, drink and clothing for men who had performed especially well as soldiers. General Cornwallis, later famous in the American Revolution, was known as a generous man who looked after all the troops in the regiment he commanded (in addition to being a general of the army). Out of his own money, he bought the men in the 33rd Regiment a heavy woolen cloak, to keep them warm and dry. Some colonels such as Hugh, Earl Percy, of the 5th Regiment of Foot, gave out good conduct medals to men who had earned them.

Yes, they did, and quite severely. An army of the 1700s, simply because of the instant obedience and discipline demanded in making sure all soldiers marched and shot at the same time, tolerated no bad behavior. Soldiers who disobeyed, deserted (left the army without permission), stole, showed up drunk, or struck each other or even officers were put in front of their regiments, tied to a post or wagon wheel, with their shirts off, then publicly and painfully whipped on the back, sometimes for hundreds of strokes. This was done to punish and humiliate the soldier who had done bad things, and to show the other soldiers who were forced to observe the whipping, that this was the fate that awaited them if they misbehaved. Sometimes the soldiers did not survive these whippings. Many sullen, disobedient British Redcoats garrisoned in Boston wore these scars on their backs for life.

Museum of the American Revolution These men are called officers. They range from the lowest officer called “ensign”, to the highest officer called “general”. There are all sorts in between, such as lieutenants, captains, majors and colonels. The colonel, whom we have already talked about a little bit, is just under the rank of general. The colonel commands the regiment, but the general commands the army which is made up of regiments. However, a general could also at the same time be the colonel of a regiment, but, because he was so busy, usually left the day-to-day running of his regiment to a lieutenant colonel.

Usually the younger sons of rich men. Elder sons inherited the family’s land and businesses, and the younger ones were forced to find other employment. To become an officer, one bought his way into the army. A father would purchase an officer’s commission in the army for his son, starting off at the lowest rank, ensign, when an available office came on the market. As the young man progressed in learning how to become an officer while on the job, he could sell his office to another man at an auction. He would then use the profits from the sale to buy a higher and more expensive office, such as lieutenant. This could go on all the way up to the office of colonel, but generals had to be appointed by the King.

Sometimes in wartime, but rarely in peacetime. Officers were born and bred gentlemen who were not royalty or nobility usually, but still came from a wealthy background. They had to have enough money to employ servants, and to be able to function in social and political situations outside of duty. This would have been difficult for someone from a lower-class background, since British society discouraged lower-class people from mixing with or becoming upper-class people. There would be some battlefield promotions of sergeants made into ensigns and lieutenants in wartime, especially since there were never enough officers to run the army. These promotions were usually not permanent.

Some British army infantry officers went to college, and military schools, when they could. Military education was just starting, but it was mostly established in places like France. Any British officers going there would go as private individuals paying their own school fees. Mostly officers learned their craft on the job from other officers, or from sergeants who would take junior officers under their wing and teach them how to command men.

NPS photo What he wore: well, the red coat. It was his outer garment that he wore year-round. The coat was made of heavy, tightly woven woolen broadcloth. It was lined with a lighter wool called “bay” and held together with over forty buttons. The coat was brick red, but the cuffs, lapels and collar were usually different in color, such as blue, green, yellow white, or black, depending on what regiment the soldier came from. The buttons all had the regimental number on them. The coat was festooned with distinctive fabric loopings called “lace”.Underneath, he wore a vest or buttoned, sleeveless woolen waistcoat, a pair of woolen breeches, long, over-the-knee woolen stockings held up by little belts around the calves called “garters”, and low shoes with brass buckle fasteners. Beneath that, he wore a long-sleeved linen shirt that when worn extended down almost to his knees. This shirt also served as his undergarment. On his legs and over his shoes he wore long linen coverings called gaiters, buttoned up as far as his thighs, to keep mud and pebbles out of his shoes. Around his neck he wore a leather stock, to remind him to look forward always. On his head he usually wore a cocked hat (which you might call a “tricorne”), but some elite troops such as grenadiers wore foot-tall bearskin caps, and light infantrymen wore short leather caps that resembled jockey caps.

First, his stand of arms: a flintlock musket, sixty-four inches long, known popularly as the “Brown Bess”, weighing twelve pounds, tipped by a seventeen inch bayonet. The soldier carried his ammunition in a pouch on his right hip, and his bayonet on a belt on his left hip. When on the march, he carried a linen shoulder bag on his left hip called the haversack for his food, and a water canteen made of tinned iron sheet. He might, if ordered to, carry a knapsack containing his blanket or cloak and spare socks and shirts, if he were to be on the march for several days.The officer’s equipment was much lighter, having a fine uniform, and he usually only carried a sword as armament. Servants, pack horses and wagons carried his camp equipment and food.

Frey, Sylvia, The British Soldier in America

Holmes, Richard, Redcoat: The British Soldier in the Age of Horse and Musket Houlding, John, Fit for Service: The Training of the British Army 1715-1795 May, Robin, The British Army in North America 1775-1783 Neuberg, Victor, Gone for a Soldier: A History of Life in the British Ranks From 1642 Reid, Stuart, British Redcoat 1740-1793 Reid, Stuart Redcoat Officer: 1740-1815 Sumner, Ian, British Colours and Standards 1747-1881 (2): Infantry and Auxiliaries

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

In this video, new and archival reenactment footage is used to demonstrate the development, adoption and use of light infantry companies in the British Army shortly before the start of the American Revolution in 1775. |

Last updated: November 6, 2021