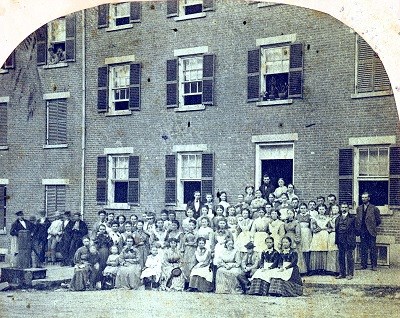

NPS Untold StoriesMuch attention has been paid to the Yankee “mill girls” who came from the farms to work in the factories, but little study has been directed towards the keepers of the boardinghouses. In the system of corporate paternalism developed by Lowell’s founders, the corporation was the substitute “father,” while the boardinghouse keeper represents the “mother.” The keeper is often thought of as a kind, matronly figure that cared for her boardinghouse as she would her own home, thinking of the mill girls as daughters. While that may have an element of truth, the keeper was also a businesswoman, responsible for keeping accurate accounts, and balancing ledgers, along with the more traditional duties of cooking and cleaning. Some saw the keeper as embodying the qualities that were desired in the ideal housewife: combining the skills of accounting and management with the proper keeping of a house.

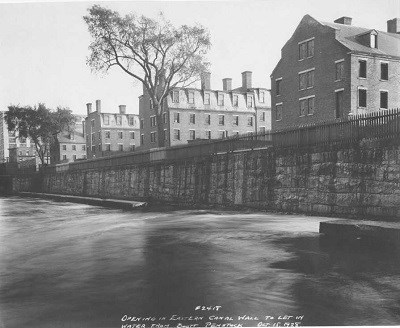

A New OppurtunityLocal Yankee women, often widows from the local middle class, were recruited to serve as boardinghouse keepers, similar to the manner in which younger women were recruited to work in the mills. It might be a mistake to think of these women as elderly, given the enormous tasks that they were required to perform. By all accounts they were probably between 45 and 55 years old. Elderly perhaps by 19th century standards! Reverend James Porter reported that “none are admitted on the corporation, as boarding masters, who are not respectable, and who will not observe the regulations of the concern [mills].” To be a keeper, a woman must have been fairly well-off financially, because she was required to furnish the house with all goods needed such as tables, chairs, beds, linens, and cookware. Since the keeper was often widowed, she may have already possessed some furnishings, but even if the woman had a large family, she would not have had tableware, beds, linens, and chairs for up to thirty people. As a result, many goods would need to be acquired by the keeper before setting up house.

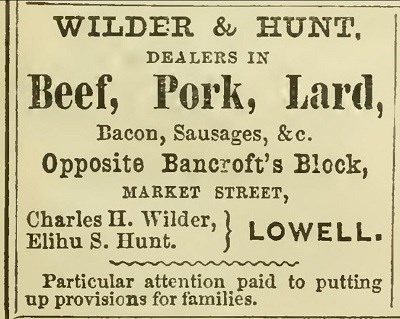

"A Woman's Work ..."The duties of the keeper involved cooking and cleaning - tasks that took up the bulk of her time. Three meals were served daily, family style. Preparation for one meal began even as the current meal was being finished. Purchasing food from local grocers would also occupy a large portion of the keeper’s time. Per corporation regulations, no outside boarders were to be fed. However, there are indicators that the keepers did feed extra boarders. Looking at probate records from Amanda Fox, a boardinghouse keeper for nearly 40 years, one can see that she had far more tableware than she had actual boarders. This could be evidence that she was feeding extra people to supplement her income; in a sense, operating a side door restaurant. Cleaning responsibilities included not only the daily upkeep of the household, but the laundry service she provided to her boarders, including work clothes and bed linens. Fancy items, mending, or pressing of pleats may have been taken on to earn extra money – if the keeper could find the time. The keeper’s responsibilities also included assuring that the girls in her house attended Sunday services, maintained a good moral character, and obeyed the rules of the corporation. Any violation of the corporation’s regulations could mean dismissal of the keeper or the worker.

The Business of Keeping HouseThe corporation would periodically inspect (or audit) the records of the keepers to insure proper expenditures and accounting for funds, so it was important that accurate records of income and expenditures were kept. A keeper who kept incomplete or incorrect records could be released. The corporation paid the keeper a stipend for each boarder in the house. In 1834, the rate was $1.25, deducted from the salary of the mill worker, plus $.25 additional per boarder directly from the corporation. From that stipend, the keeper purchased all necessary items to conduct business at the boardinghouse. This would include food, tableware, linens, pots and pans, coal or wood, and furniture. Any leftover money was her profit. The keeper was constantly facing a battle – how to balance serving good wholesome meals to ensure a full house of boarders, with the need to spend less on goods than she took in from the corporation. Sometimes the choices made meant serving soup beef much more frequently than roasting meat in order to get more for her food dollar. Think of managing a household today – who wouldn’t love to have the best cuts of meats, the choicest fruits and vegetables and only fresh fish. But choices are made based on income, quality and value. It was no different for a boardinghouse keeper. Many of the keepers with young daughters found that by sending their daughters to work in the mill they could receive the stipend for their meals, and the extra $1.75 would have eased the strain somewhat. However, that also meant the loss of a pair of hands to assist in meal preparation and clean up, which could mean the necessity of hiring outside help. If the costs of the outside help were less than the wages the daughter’s work would bring in, it would be an adequate trade.

A Noble ProfessionIn many ways the job of a keeper was not in step with the ideals of the time. “Women’s work” revolved around the home and the “cult of domesticity,” which limited opportunities for women in business and certainly in management. However, since this position was clearly located within the “women’s sphere” of the time, it seemed to be an appropriate occupation for a woman. Even Catherine Beecher, an advocate for women remaining in the home to care for the family, found being a boardinghouse keeper to be a noble occupation. In her Treatise on Domestic Economy in 1841, Beecher wrote that the keeper should serve as a model for other women, in her use of professional methods of managing a household and keeping accurate records. Surrogate mother, professional businesswoman – the keeper embodied the best of both. |

Last updated: November 15, 2018