Mill AgentsTo the workers in Lowell’s textile mills, a mill agent’s house must have seemed an important place. It was the home of the person who controlled all aspects of the company’s day to day operations. The mill agent arranged for the maintenance, repair, and replacement of the machinery, oversaw all the different activities in the workrooms, and had the power to hire and fire employees. The agent was a salaried employee. Along with this often impressive salary he was allowed to reside in the agents house with his family and he had options to buy company stock. To the average worker he must have appeared to be one of the most powerful men in the city. The mill agent was often the highest-ranking corporation employee who lived in the city, but was by no means the true master of the mill. The agent reported directly to the mill company treasurer, who usually lived in Boston or some other place outside the city of Lowell. The treasurer was responsible for all the financial affairs of the company. He bought the raw cotton and helped set the price for the finished cloth. Usually a major stockholder chosen for the job by the other stockholders, the treasurer reported directly to the board of directors. These directors were the true masters of the mill. They were the primary stockholders, and although most of the everyday business of the company was taken care of by the agent and treasurer, they were the ultimate decision makers on company policy.

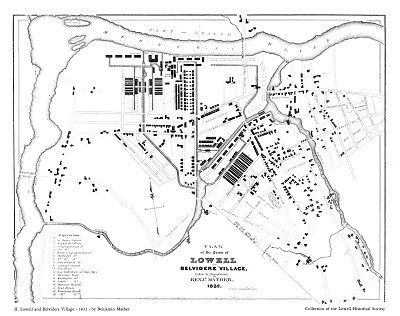

New IdeasBy establishing the mills in Lowell, the directors of Lowell’s textile companies sought to create a system of organization and management that was different from that seen in earlier New England textile companies. They wanted to establish companies that could provide a comfortable level of return over a long period of time with minimal risk to the individual investor. They also wanted to create a work environment different from those found in England and Rhode Island. Great Britain’s factory cities were crowded, dirty, and contained harsh and often unreasonable working New Ideas conditions. Mills in Rhode Island used whole families as their work force and paid in company money. In order to give the Lowell mills a solid foundation, they were capitalized at previously unheard of sums of money. The Merrimack Manufacturing Company, the first mill company established in the area that would eventually become Lowell, was initially capitalized in 1821 at $600,000 and by 1823 had expanded to $1,200,000. The money was assembled from private stock sales to a closely connected group of family, friends, and business associates. These large sums allowed the companies to hold aside considerable amounts of money to help them survive changes in the market. As the mills of Lowell continued to grow and expand, these investors began to make other investments that they felt would keep their companies strong and successful. They bought stock in early railroads to help them move raw materials and finished goods back and forth. They established their own machine shop so they could invent and build newer and better machines. They invested in banks and insurance companies to make sure they could get loans for even further expansion and growth and reduce the risk of losses from fire. To avoid what they saw as the failures of England’s textile cities, the investors created a system of “corporate paternalism.” They chose for their primary work force young women from rural New England. These young women were seen as surplus labor at the time and could be hired at much lower rates of pay than men. The investors saw themselves as the benefactors of these young women and provided them with clean, safe, company-owned boardinghouses and cash pay. They also supported opportunities for self-improvement such as lending libraries, concerts, lectures, and night classes.

Center for Lowell History Early SuccessesThroughout the first few decades of Lowell’s history, these factors combined to make its mill companies very successful. The investors were able to make comfortable profits from their investments and the workers found new jobs and opportunities. Lowell was praised by many as a clean, industrious marvel of its day. Unfortunately, this “golden age” of prosperity was short-lived and competing mill cities were established as early as the 1830s using the successful “Lowell system” as a model. Strong competition began to erode Lowell’s dominance of the textile market, and as profit levels began to decline, ideas of “corporate paternalism” began to fade. Changing IdeasAs the years went by, the number of stockholders was increased through inheritance and public sales. These newer stockholders became less interested in the routine affairs of the companies and more interested in maximizing profit levels. Agents, once “hired gentlemen” of good family and reputations, were replaced by experienced professional managers with technical backgrounds. More often than not these later agents had worked their way up through the management system. By the end of the 19th century, most of Lowell’s “mill girls” had been replaced by an army of immigrant families from across the globe. Conditions in the workrooms worsened until they resembled the conditions that the original shareholders wished to avoid. In the 1920s and ‘30s the mills were considered no longer sufficiently profitable and were shut down, sold off, or reorganized in the South where tax and labor situations were more suitable.

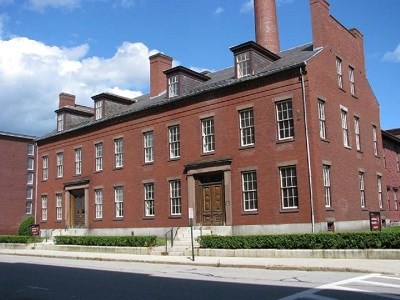

The Agents House TodayThe Massachusetts and Boott Mills Agents House on Kirk Street (front, top) has been preserved to serve as a symbol of the management and capital that formed the Lowell mills. Built in 1845-1846, it is a duplex that provided separate housing for the agents of both the Boott Cotton Mills and the Massachusetts Cotton Mills along with their families and servants. This duplex form is unique among Lowell’s agents houses and illustrates the close connections between the Massachusetts and Boott Mills. At one time surrounded by corporate housing and part of a thriving neighborhood, the house was sold in the first decade of the twentieth century. The city had grown in size and new neighborhoods had developed. The downtown was becoming more and more a retail and industrial area. The companies built new, often grand homes outside the mill district and the agents moved to these more prestigious addresses. The structure was converted into a rooming house and later used as a health clinic annex of Lowell High School, located across Kirk Street. Acquired by the National Park Service, it now serves as the headquarters of Lowell National Historical Park. |

Last updated: November 10, 2018