|

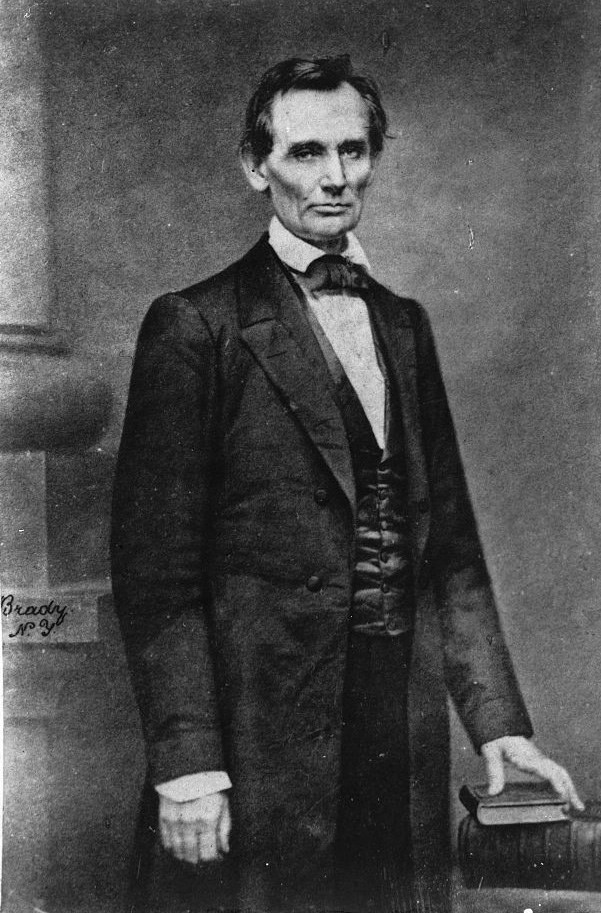

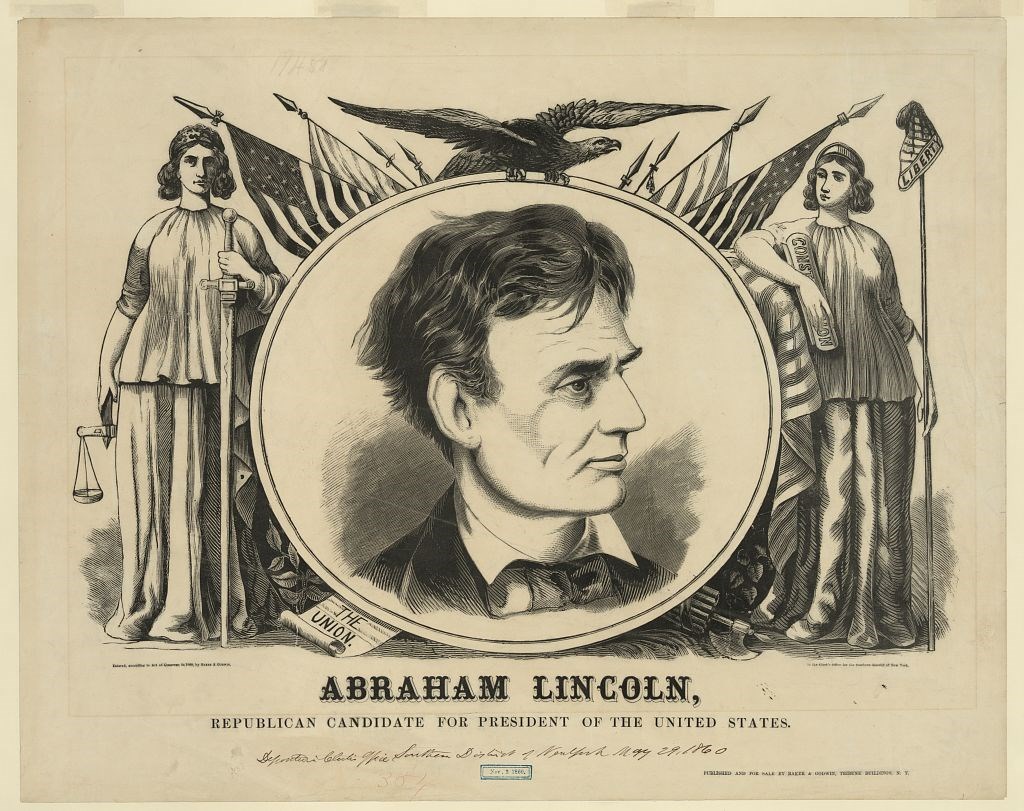

Toward the end of 1859, in New York D. W. Bartlett published Twenty-one Prominent Candidates for the Presidency in 1860, and in early 1860 a Philadelphia publishing house printed John Savage's Our Living Representative Men, Prepared for Presidential Purposes. Abraham Lincoln was not listed among the "prominent candidates" in the former, nor was he considered "prepared for Presidential purposes" in the latter (Freeman 1960, 76-77). Yet, on May 18, 1860, he was chosen as the Republican Party's candidate for the Presidency. In a few short months he had risen from a relative unknown to winning the Republican Nomination. The Cooper Union Address, delivered in New York City on February 27, 1860, helped to propel Abraham Lincoln to the 1860 Republican Nomination.

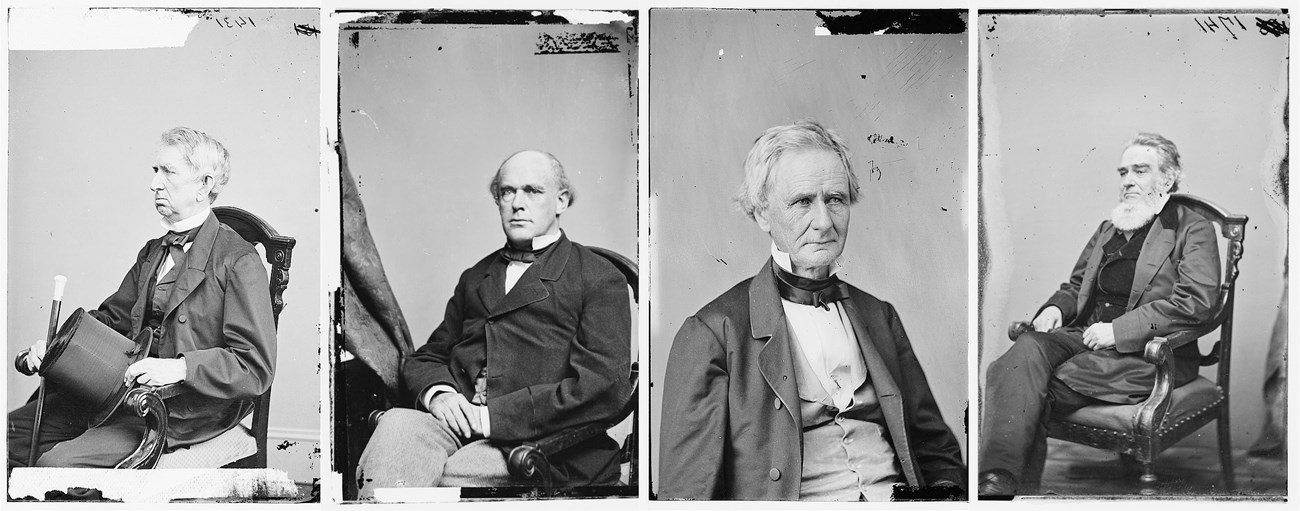

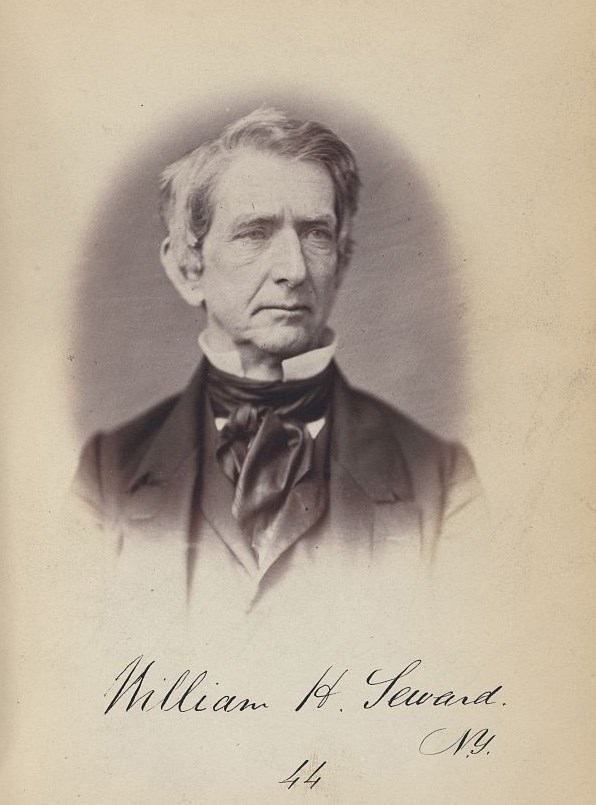

Library of Congress Lincoln's Second ChanceThe Lincoln-Douglas Debates are often cited as the instrument that thrust Abraham Lincoln into national prominence. But Lincoln did not win that 1858 Senate race. In a letter to Dr. Anson G. Henry following his loss to Douglas, Lincoln wrote: "I am glad I made the late race. It gave me a hearing on the great and durable questions of the age, which I could have had in no other way, and though I now sink out of view, and shall be forgotten, I believe I have made some marks which tell for the cause of civil liberty long after I am gone" (Donald 1995, 229). In today's vernacular, in Lincoln's own estimation he had had his "15 minutes of fame." Abraham Lincoln continued to make political appearances and his speeches were warmly received in Iowa, Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Kansas in 1859. However, only his staunchest supporters considered him a leading candidate for the 1860 Republican Nomination (Donald 1995, 235). The leading candidates were William Henry Seward of New York, Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania, Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, and Edward Bates of Missouri. Among the leading candidates, Seward was the favorite. However, many Republicans thought Seward could not be elected. He was considered an extremist since his speeches proclaimed a higher law than the Constitution, and predicted an irrepressible conflict between slavery and freedom (Donald 1995, 236). Seward also had substantial opposition in his own state. Thurlow Weed, Seward's benefactor and advisor, dominated Republican politics in New York. However, William Cullen Bryant, Horace Greeley, Hamilton Fish, and David Dudley Field were opposed to Weed. They, under the auspices of the Young Men's Central Republican Union of New York, decided to search for another, hopefully more moderate candidate, a candidate they thought could win (Nevins 1950, 183). The prospective candidates were invited to New York to give addresses. Abraham Lincoln's speech would be the third in a series, following the Missouri anti-slavery leader Frank Blair and the Kentucky abolitionist Cassius Clay (Freeman 1960, 52-53).

Library of Congress Lincoln Takes his Turn at the LecturnAbraham Lincoln knew why he had been invited to New York City to give a speech before the Young Men's Central Republican Union of New York. He was being "trotted out" as an alternative to Blair, Clay, and most importantly, Seward. Originally, the speech was to be delivered in Henry Ward Beecher's Plymouth Church in Brooklyn. At the last moment it was switched to the brand new Cooper Union in lower Manhattan, and was scheduled for Monday, February 27, 1860 (Freeman 1960, 13-17). Lincoln made his address on a snowy night before about 1,500 persons. On the platform with Lincoln were many distinguished New York Republicans: David Dudley Field, a prominent New York lawyer; William Cullen Bryant, editor of the Evening Post; John A. King, former governor of New York; George Palmer Putnam, publisher; Theodore Tilton, editor of The Independent; Henry M. Field; Charles Nott; and Horace Greeley. William Cullen Bryant introduced the man from Illinois to the audience (Freeman 1960, 80-81). Lincoln had been preparing his speech for months. His primary source had been the six-volume Debates on the Federal Constitution by Elliott. He also consulted the official record of the proceedings of Congress, the Congressional Globe, American history books, and other sources (Freeman 1960, 51). Lincoln's speech can be divided into three parts. In the first, he showed that twenty-one of the thirty-nine signers of the Constitution were on record that the Federal Government could prohibit slavery in the national territories. In the second, Lincoln explained to the South that Republicans were no threat to slavery where it already existed. Finally, Lincoln spoke to the North. They must fearlessly persist in excluding slavery from the national territories, and therefore, confine it to the states where it already existed (Donald 1995, 238-239). The ReviewsThe text of Abraham Lincoln's Cooper Union Address was widely circulated. Lincoln himself supervised the proofs that were published in the New York Tribune (Freeman 1960, 92-93). Three other New York newspapers also printed the entire speech (Donald 1995, 239-240). The New York Tribune, Times, and Evening Post all ran complimentary headlines, articles, and editorials (Freeman 1960, 94-96). Later, the speech was reprinted in the Chicago Press and Tribune, the Detroit Tribune, and the Albany Evening Journal (Donald 1995, 239-240).

Library of Congress The Seward ComparisonWilliam Henry Seward sensed the conservative movement was against him and he knew he must strike a more moderate pose (Van Deusen 1967, 221). Many questioned whether Seward could win in the highly contested states of Illinois, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania (Taylor 1991, 110). He understood the questions of electability and knew he must deliver a major speech with a more conciliatory tone (Nevins 1950, 181). On February 21, 1860, he announced he would make an important address on Kansas statehood on February 29 (Bancroft 1967, 511). Seward's address was made as much to the country as to the Senate. He said there was only one Republican principle, the exclusion of slavery from the territories. He spoke of "capital States" and "labor States," not "slave" and "free" states. He avoided any mention of a moral difference between the sections; he suggested the differences were merely economic. Seward condemned John Brown's raid and he contended the South misunderstood Republicans. Republicans only objected to the introduction of slavery into the territories by a surprise measure (Nevins 1950, 181-182). Seward's and Lincoln's speeches went to the reading public at the same time (Nevins 1950, 187). While Seward's address strengthened him and the Republicans, Lincoln's, given two days earlier, was clearly superior. It was more candid and had more intellectual arguments. It was based upon more research. Lincoln did not gloss over the issues, but confronted them. He expressed a positive conviction, rather than ignoring the moral issue (Nevins 1950, 187-188). This set the stage for the Republican Convention held two months later. Securing the NominationThe 1860 Republican Convention was held in Chicago and began on May 16. Balloting for the presidential nomination took place on May 18. It took 233 votes for a candidate to receive a majority. On the first ballot, Seward had 173 votes, Lincoln 102, and most of the rest were scattered among several favorite sons. The Seward campaign managers had counted on all ten of the New Hampshire votes, but seven of New Hampshire votes went to Lincoln on the first ballot. On the second ballot, nine of the ten New Hampshire votes went to Lincoln. The whole Vermont delegation switched from favorite son Jacob Collamer to Lincoln, and a large percentage of the Connecticut and Rhode Island delegates switched to Lincoln. The whole Pennsylvania delegation also switched to Lincoln. At the end of the second ballot, Seward had 184 1/2 votes and Lincoln had 181 votes (Van Deusen 1967, 223). On the third ballot, Massachusetts changed four votes to Lincoln, Ohio gave twenty-nine of its forty-eight votes to Lincoln, and Maryland swung all its votes to Lincoln. The result was Seward 180 and Lincoln 231 1/2. Lincoln was just 1 1/2 votes short of a majority (King 1960, 141). Before the results of the balloting were even announced, the chairman of the Ohio delegation rose to announce a shift of four votes to Lincoln. Others then rose to shift their votes to Lincoln, and finally, the chairman of the New York delegation rose to ask that the nomination be made unanimous. So on the third ballot, Abraham Lincoln became the Republican nominee for President (Van Deusen 1967, 224-225).

Library of Congress The Making of a CandidateAt the beginning of 1860 Abraham Lincoln was not considered as a major candidate for President. Rivals of New York Republican leader Thurlow Weed were looking for an alternative to William Henry Seward. These rivals set up a "test" to find this alternative candidate. by Gene Finke Acknowledgements Thanks to the following for their assistance: Jeff Budny, Kathy DeHart, Tim Good, Susan Haake, Norm Hellmers, Ann Johnson, Christy Lindberg, Kip Lindberg, Cathy Mancuso, John Popolis, Jim Ranslow, Lynn Rempfer, Mike Starasta, Tim Townsend, and Kevin Weber.

Bancroft, Fredric. 1967. William H. Seward. Gloucester, Massachusetts: Peter Smith. Freeman, Andrew A. 1960. Abraham Lincoln Goes to New York. New York: Coward-McMann, Inc. Miers, Earl Schenck. 1991. Lincoln Day by Day. Dayton, Ohio: Morningside House, Inc. Nevins, Allan. 1950. The Emergence of Lincoln. New York: Charles Scribners' Sons. King, Willard L. 1960. Lincoln's Manager: David Davis. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Taylor, John M. 1991. William Henry Seward: Lincoln's Right Hand. Washington: Brassey's. Van Deusen, Gyldon G. 1967. William Henry Seward. New York: Oxford University Press. Wiley, Earl Wellington. 1970. Abraham Lincoln: Portrait of a Speaker. New York: Vantage Press. Go to Text of Cooper Union Address |

Last updated: May 11, 2021