Left image

Right image

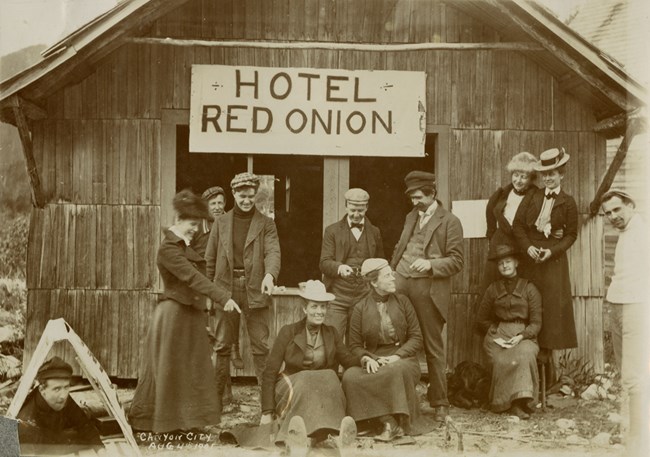

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George & Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55949e. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. After the Gold RushBy 1899 the White Pass & Yukon Route (WP&YR) railroad had been completed to Bennett, but the gold rush was largely over. The Chilkoot Trail became unused and overgrown. Many of the hastily built structures along the trail were dismantled for firewood or timber. Gear and machinery that could be moved was taken off the trail. The tramway machinery was broken down and removed in 1900 after its purchase by the WP&YR. By fall 1899 the Alaska Mining Record reported that there was not “a restaurant or hotel to be found” on the trail.In 1906, International Boundary Commission surveyors retraced the Chilkoot Trail to determine the boundary. O.M. Leland, head of the American party, reported that the trail was overgrown and rough. The old bridges of 1898 were dilapidated. However, most of the buildings at Sheep Camp were still standing, as well as two buildings at the Scales.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George & Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 59774. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. The "Lost" YearsAs a result of the trail’s deterioration, trail use was sporadic and mostly recreational.Between 1910 and 1925 local resident George Rapuzzi made four trips up the trail from the American side. In the early 1920s he led an MGM movie crew up the trail. This crew was scouting the location for the upcoming Charlie Chaplin film, The Gold Rush. They were investigating filming the movie on location. Despite 25 years of neglect, the trail was still passable with heavy use of the wagon road from Dyea to Canyon City. In July 1928 Florence Clothier and her brother Lou climbed the Golden Stairs. In 1933, Reverent G. Edgar Galland, superintendent of Skagway’s St. Pius X Mission, began taking small groups of students over the trail. At the same time, Bryne Beauchamp, a teacher from Honolulu, Hawaii, organized annual trips. These trips included hiking the trail and building boats to float down the Yukon River to Circle City, Alaska. A road connecting Skagway and Dyea was built in the 1940s allowing increased access to the trail. About 1947 Al Nelson, a Dyea resident, blazed a crude trail up the eastern bank of the river. This route avoided river crossings and became known as “Saintly Hill.” In 1947 Phillip Allen hiked the trail north to south as part of a longer trip tracing the Trail of ’98. As he stood at Chilkoot Pass on Sept 28, 1947 he remembered “The year 1898 came suddenly to life. […] a faint wind whispered through the gap.[…] It was the combined voice of the Argonauts of ’98. It cursed the rain, the slipshod trail and the very day they left civilization, with every step of leather on cold, wet rock.” In 1948 the Hosford family built a sawmill complex a few miles up the trail. To access the site and commercial grade spruce trees, they developed a road on the east side of the river all the way to Finnegan’s Point. This logging operation ran until 1956. "Rediscovery"In 1957 and 1959, Anchorage residents Robert and Wilma Knox and their friend Richard White hiked the remains of the trail. In 1957 this group found large sections of the route very hard to navigate with almost no signs of a trail. As they got above Stonehouse trail evidence became much more apparent.On their second trip in 1959, the group hiked the trail from the Canadian side down the Pass to camp at the Scales. At the Scales they counted and identified gold rush artifacts. In addition to the tramway towers, there were pieces of rubber, canvas, and leather; stove parts; Seattle newspapers dated 1906; cake tins and cooking pots; pan animal bones; rotting milled lumber; ink bottles; crampons; and much more. From the two hikes, Robert Knox, a writer for the Anchorage Daily News, published a number of articles in the late 1950s. These feature stories and the publication of Pierre Burton’s Klondike (1958) generated interest in the trail as a destination for hikers and campers. In 1961 the National Park Service began inventorying historic sites in Alaska. Dyea, the Chilkoot Trail, Skagway, and the White Pass trail were all included in this study. While the Chilkoot was not recommended for listing at that time, it renewed interest in the trail.

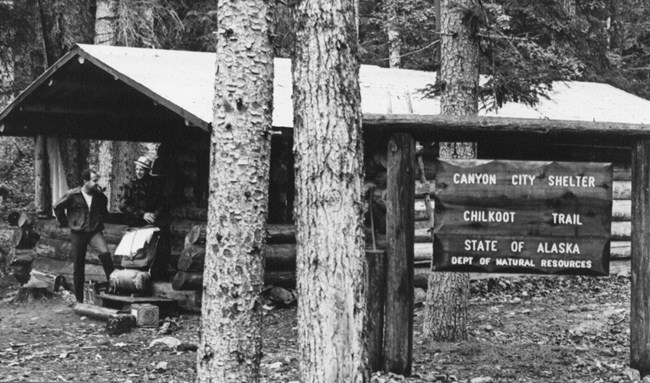

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Mike Miller Collection, KLGO 47129. Trail Work BeginsThe State of Alaska began work to open a recreation trail following the route of the Chilkoot. Much of the work was done by prisoners participating in the state’s Youth and Adult Authority (YAA) rehabilitation program. YAA participated in projects offering long-term recreational benefits. The Alaska Department of Natural Resources, Division of Lands provided technical oversight. The trail that was surveyed and constructed led entirely up the eastern side of the Taiya River, thus missing significant sections of the historic trail. Much of the trail below Canyon City was non-historic. The modern trail, with few exceptions, dates to the years of state-directed construction, 1961-1968. These early crews experienced many of the same difficulties that still challenge the park’s trail crew. High waters on the Taiya River flooded sections of the trail, washed out embankments, and swept away bridges. During the 1962 season the YAA crew built a 16 ft by 20 ft log cabin near Canyon City. This cabin would serve as an overnight destination for hikers, but would be used as YAA headquarters during their trail work. During the 1963 season the YAA crew built a shelter cabin at Sheep Camp. The shelter measured 18 ft by 22 ft and had a corrugated aluminum room. Supports for a covered porch on the cabin were held in place by cast iron cable drums—artifacts scavenged from the area.In 1967, the 100th anniversary of the purchase of Alaska, a commemorative stone marker was dedicated by the State of Alaska at Chilkoot Pass. That summer the first Chilkoot Trail hiker’s guide was published. The guide included a brief trail history, a description of major historical resources along the train, and information about recent improvements. The National Service Gets InvolvedThe modern trail was officially open and completed in 1968. In 1972 an estimated 1,000 people hiked the trail. As more people began to hike the trail, it became clear that effective preservation and management couldn’t happen without federal assistance. Also in 1972 NPS began to work with the State of Alaska to maintain the Chilkoot.In 1975 the Chilkoot Trail was placed on the National Register of Historic Places and amended to include Dyea in 1978. On June 30, 1976 President Ford authorized the establishment of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. In 1978, archeologists inventoried, surveyed, and assessed the trail. This work became the basis for trail management. The NPS discussed relocating the recreational trail to more accurately match the historic summer trail. Ultimately, the trail was not relocated due to the potential for degradation of archeological resources.

NPS photo |

Last updated: February 7, 2017