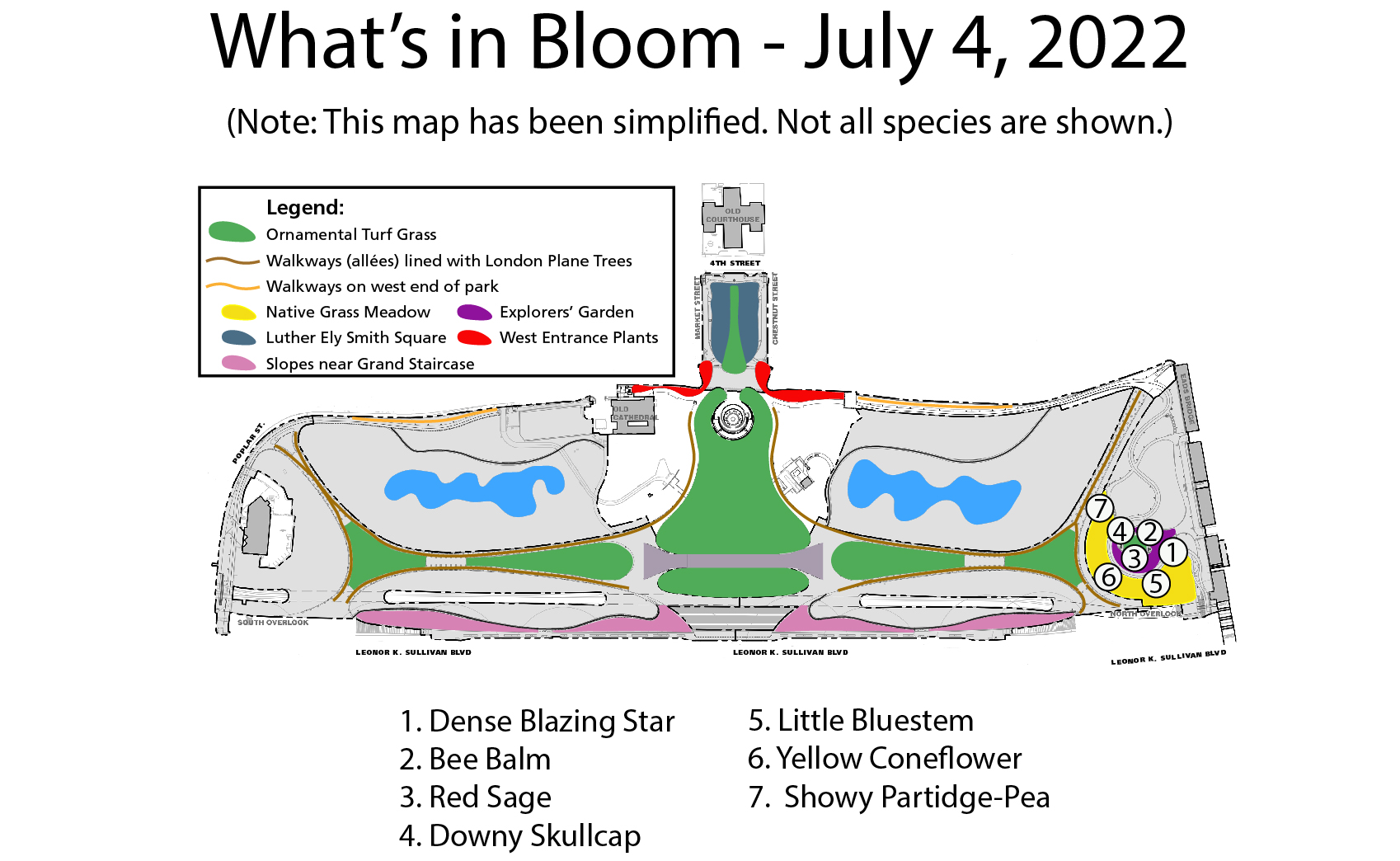

1. Dense Blazing Star, Liatris spicata. Blooming in the Explorers' Garden.

This is arguably the showiest flower in the Explorers’ Garden right now. It has the shape of a large bottle brush made of tiny, dense purple flowers. It’s native to the eastern US, but Missouri is at the Western extreme of its range; in the wild, it has only been seen in southeast Missouri near the Arkansas border. It loves wet areas such as marshes, but can live in other places as well; once established it is very tough and hardy. It can survive considerable heat, cold, and drought. Since the time this species was first encountered by European colonists, it has also been a popular garden specimen in Europe.

Dense Blazing Star is a great species for many insects: a few different species of moth caterpillars eat the foliage, and the blossoms are excellent pollinators for many bees and butterflies. NPS Photo.

2. Bee Balm, Monarda bradburiana. Currently blooming in the Explorers' Garden.

NPS Photo

As you might have assumed by its name, bees and other pollinators flock to bee balm. The species is a native to the area. It naturally occurs in several Midwest and Southern states, but the greatest distribution is in Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Bee Balm's blossoms look a little like exploding fireworks; how appropriate for the 4th of July! NPS Photo.

3. Red Sage, Salvia coccinea. Blooming in the Explorers' Garden.

NPS Photo.

NPS Photo.

In warmer climates (from Florida to South Carolina and westward to Texas), this stunning plant grows all year long. Here in St. Louis, it can’t survive our harsh winters. It does, however, put out seed every fall and grow back as an annual. Hummingbirds are especially fond of this plant. If you rub a leaf during your visit, you will notice a very strong and persistent herby smell.

4. Downy Skullcap, Scutellaria incana. Currently blooming in the Explorers' Garden.

Photo by A. Prosser, NPS

Photo by A. Prosser, NPS

If you look very closely at this species’ blossoms, you might notice that they’re covered in soft hairs: that’s where the “downy” in their name comes from. The “skullcap” part comes from the flower’s shape. It’s a Missouri native, widespread in the Ozark region. Insects (especially carpenter bees) like to climb deep inside the flower to eat pollen and drink nectar. This species grows best in dappled sunlight, so the individuals growing under the shade of the Catalpa trees are particularly vibrant and healthy.

5. Little Bluestem, Schizachyrium scoparium. Currently blooming in the native grass meadow.

Photo by A. Prosser, NPS.

Photo by A. Prosser, NPS.

This grass is found in every US state but Nevada and Oregon and is also widespread in Canada. It’s the official state grass of Nebraska and Kansas. Don’t let the name “little bluestem” fool you: like all grasses, it is mostly green. However, if you look closely at the stem’s base it does have a silvery-bluish tone. Once established, little bluestem has a very deep, dense root system and can easily survive being mowed or burned (or eaten by herds of roaming bison). In fact, regular burning or mowing actually improves a population’s health! It’s the host plant for at least six species of butterflies.

6. Yellow coneflower, Ratibida pinnata. Currently blooming in the native grass meadow.

Photo by A. Prosser, NPS

This yellow coneflower is very similar to the Rudbeckia missouriensis previously mentioned on this blog. It’s native to the central and eastern USA and Canada. The yellow blossoms drop down more than some other coneflowers, so the flower sort of resembles a tulle skirt. Like many other prairie plants, it is very hardy and spreads slowly through rhizomes.

7. Showy Partridge-Pea, Chamaecrista fasciculata. Currently blooming in the native grass meadow.

NPS Photo.

Only a few individuals of this very pretty species are growing in the Prairie, but their large bright flowers make them easy to find. Since this plant is in the bean family, it fixes nitrogen and improves soil quality. It’s the host plant for at least two moth caterpillars, and its blossoms are enjoyed by many pollinators. Sometimes it's called “sensitive plant”, and there are a couple reasons for that: 1) it closes its leaflets at night, and 2) when the dried seed pods are disturbed, they will suddenly split and fling the tiny black seeds several feet from the parent plant. This interesting seed dispersal method helps the plants spread. If left unchecked they can spread too aggressively and be considered invasive in some locations.

Bonus!

NPS Photo

This isn’t a flower, but it’s interesting and worth mentioning anyway: the Baptisia alba that was blooming a few weeks ago has produced its large seed pods! They will turn dark as they mature and eventually split to release the seeds. The bean-shaped pods are larger than you might expect – nearly 2 inches!