NPS/Harpers Ferry Center The seventeenth century outbreak of the Great Northern War meant that England could no longer get their iron from Sweden. This provided the colonial iron makers of Maryland’s Chesapeake region with a great opportunity. England needed iron and the Chesapeake had all the raw resources – iron deposits, heavily wooded areas for wood to make into charcoal, limestone deposits and access to waterways – but no existing furnaces. To meet this new demand, the Legislature of Maryland passed laws during the first quarter of the eighteenth century to promote the development of ironworks.

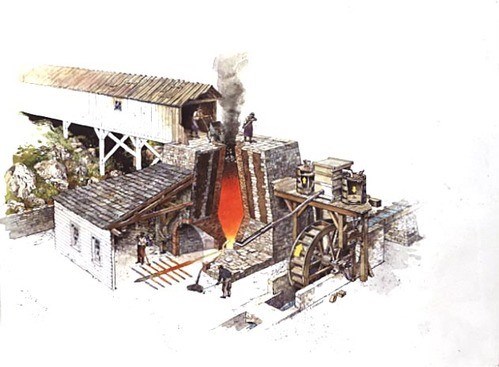

NPS/Tim Ervin Maryland colonists, including Colonel Charles Ridgely, established many highly productive ironworks. Colonel Ridgely’s purchase of the tract of land called “Northampton” in 1745 was the first of many land purchases for his business and his family. By 1762, due to the clearing and building efforts of teams of indentured servants, enslaved laborers and paid workers, the Colonel had developed Northampton as an ironworks that made and sold pig iron and iron products. In 1763, the Colonel’s younger son, Captain Charles, retired from the sea to operate a general merchandise and importing business in Baltimore Town and focus on his duties with the Northampton Company. After Colonel Ridgely’s death in 1772, Captain Ridgely owned a two-thirds controlling interest in the iron company, which he managed along with his brother-in-law, Darby Lux.

NPS The American Revolution found the Ridgelys aligned with the Patriot cause. The ironworks turned out camp kettles, round shot ranging from 2 to 18 pounds, cannon shot and cannons of various sizes and other supplies for Continental troops. Guns from the works were judged at the time “to be the equal in quality of any yet made on the continent.” War profits from the ironworks allowed Captain Ridgely to greatly expand his property holdings, in part by buying up confiscated Loyalist property, which included more enslaved laborers and indenture contracts. |

Last updated: July 8, 2020