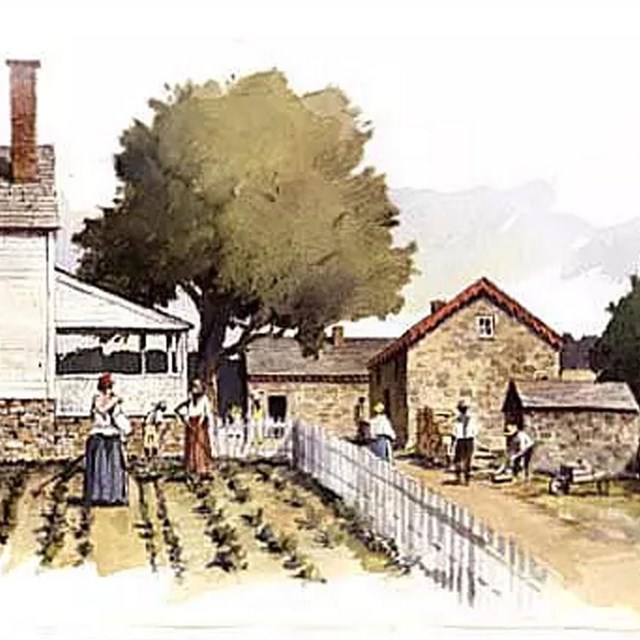

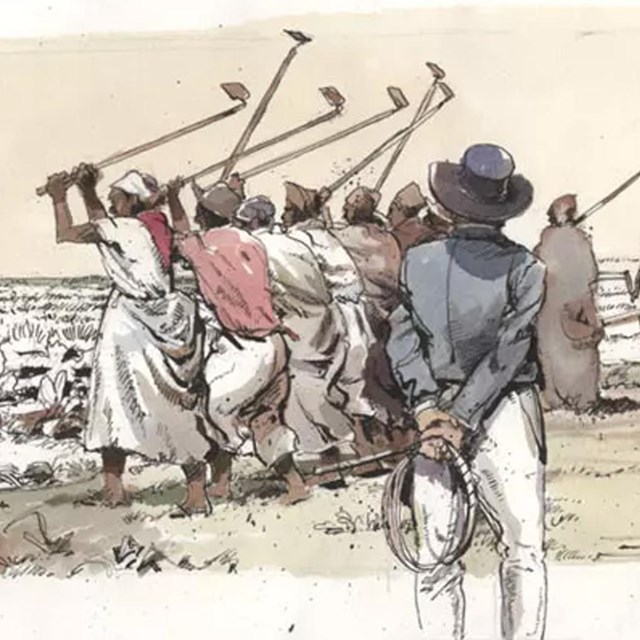

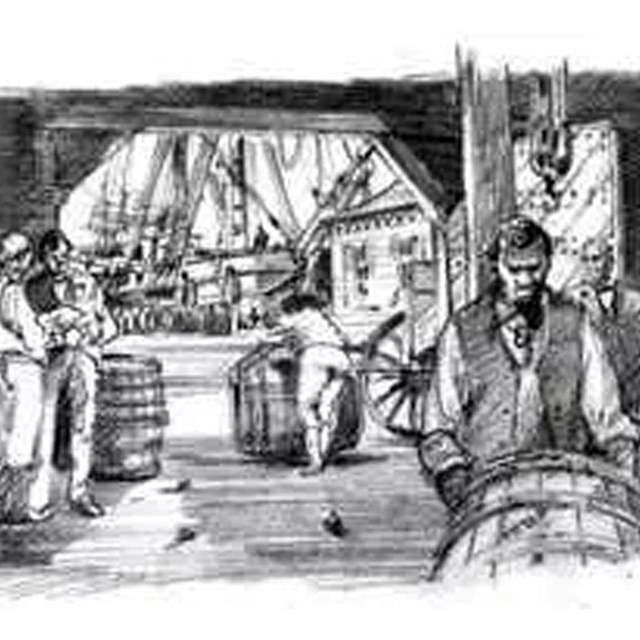

NPS/Richard Schlecht Illustrations The term "Freedom Seeker" illustrates the decision of the enslaved person to take control of their destiny from the enslaver by leaving the site of enslavement. Other terms that have been used in the past are "fugitive" and "runaway". The decision to seek freedom was difficult. Not only did an individual face possible capture, corporal punishment, and an unknown world beyond Hampton, they often left behind family they might never see again. It is unknown whether the 76 or so enslaved individuals who sought their freedom from Hampton over t used the Underground Railroad. A network of people who hid, fed, and guided thousands of enslaved individuals seeking to escape, the Underground Railroad was particularly strong in Maryland. Those providing help included free and enslaved Black people, Indigenous People, white people, Quakers, Methodists, and Baptists. Hampton’s freedom seekers had the advantage of being in close proximity to Baltimore City, where a large community of free Black people made it easier to hide. Hampton was also close to the border of Pennsylvania, a free state. However, after Congress passed the “Fugitive Slave Act” of 1850, making it across the state line was no longer a guarantee of safety. Freedom seekers often set out for Baltimore City where they might hope to be supported by a large free Black community or for Pennsylvania, a “free state” with laws making it difficult for human traffickers and enslavers to pursue and recapture them. Some freedom seekers did not even look for their own freedom but rather sought to return to family members on other plantations. Over 80 enslaved people sought their freedom from Hampton throughout the time people were enslaved at Hampton. Large groups of freedom seekers were generally doomed to failure and most successful journeys to freedom were taken by young men traveling alone or in pairs. Some notable exceptions include the teenaged Rebecca Posey and housekeeper Lucy Jackson. The stories of freedom seekers can be as devastating as that of a laborer enslaved by Abraham Pattern. This laborer was hired out by Pattern to the Ridgely’s to work at the Northampton ironworks on March 18, 1774. According to the Northampton Furnace Journal, 1775-1778, the worker complained that he was constantly “sicke” and could no longer work. His pleas were ignored so he sought his freedom but was soon captured. In despair, he “cut his throat” rather than continue to labor for the Ridgelys at Northampton furnace. This act caused Patterns to retrieve him and remove him from the site. Such were the harsh conditions that some enslaved people would rather endure self-induced bodily injury than continue at the Northampton ironworks.

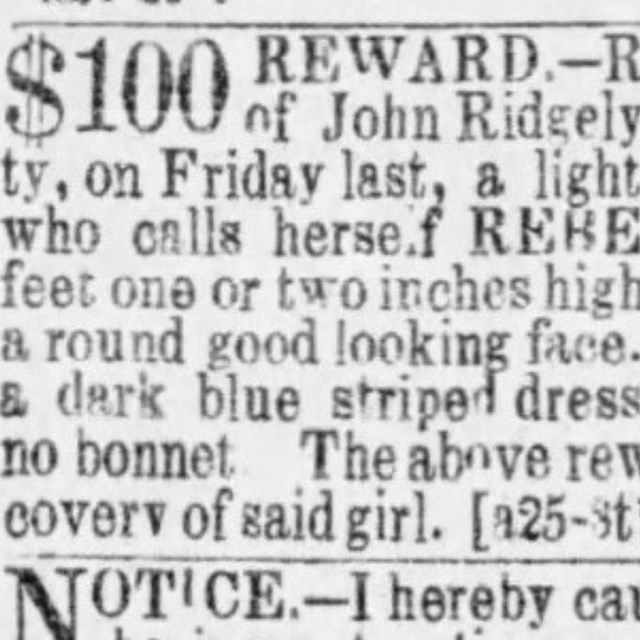

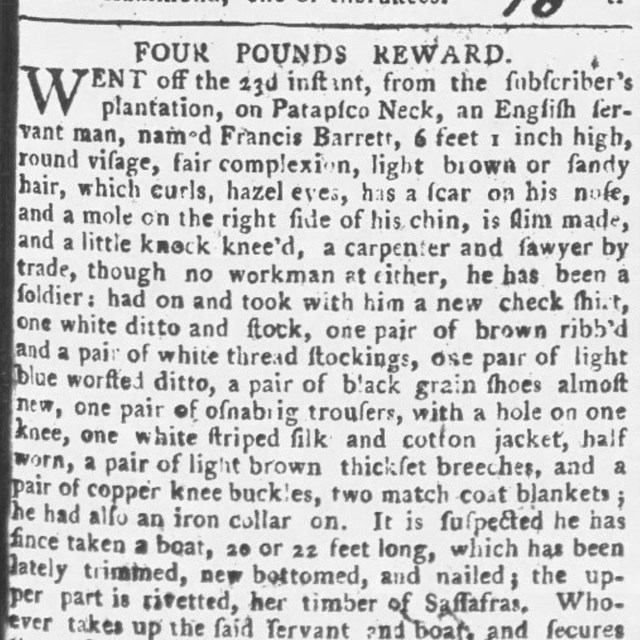

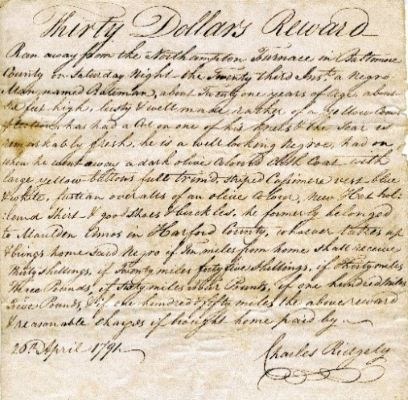

NPS A letter from Walter Bowie to Charles Carnan Ridgely dated February 20, 1796: “Mr. Barton has been so fortunate as to get your man and I have no doubt will get him safe home. I could wish if it is possible . . . that you have instructions not to whip him, as he appears to be truly penitent for transgression. He very much laments the parting from his wife and says he will stay with you if you purchase his wife….” Enslaved freedom seekers were not the only ones to decide to leave Hampton's ironworks. European white indentured servants would seek their freedom as well, as is evident in advertisements printed in newspapers. Between 1770 and 1820, there were at least thirty ads for freedom seekers from Hampton placed in local newspapers. A 1791 reward notice, handwritten by Charles Carnan Ridgely, advertised for the return of Bateman, a young, enslaved man recently purchased from a Harford County plantation. Bateman must have been captured and returned since he appears in later Hampton records. By the time of Charles Carnan Ridgely’s death in 1829, he was no longer working or living at the Northampton Furnace but was recorded at the Hampton Home Farm. Bateman was then 58 years old and too old to be freed by the governor’s will. Another advertisement brings to light the story of a man named Hercules, enslaved by the Charles Carnan’s son, Charles Ridgely Jr. The list of clothing received by enslaved people at the Epsom farm demonstrates that Hercules and his wife were on the site during the period from 1811 to 1817. During that time, it seems likely that Hercules attempted to seek his freedom. On August 21, 1813, Charles Ridgely, Jr., ordered an iron collar and two shackles made for him by a blacksmith, at a cost of fifty cents. These were items of confinement, normally purchased to constrain the liberty of an enslaved person who had previously attempted seeking their freedom. Ultimately, at age 41, Hercules was manumitted, or freed, in 1829 by the terms of Charles Carnan Ridgely’s will, one of the 74 adults who were freed immediately. However, following freedom, Hercules stayed on at Hampton as a low wage employee.

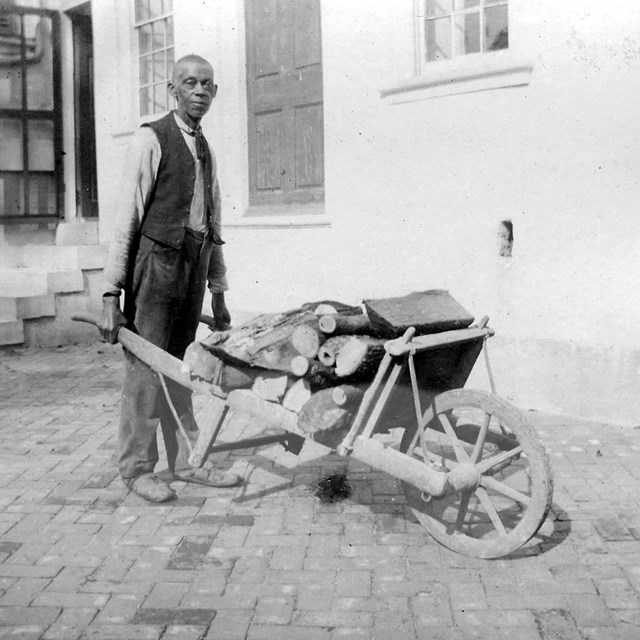

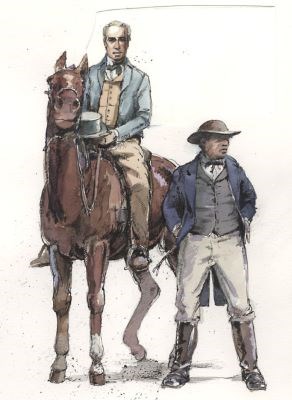

NPS/Harpers Ferry Center Farm laborer Henry Jones was more fortunate than many. He left Hampton in 1853 and was never recaptured. Over forty years later, Nancy Davis recalled that he “Ran away and & got clear....” By the early 1830s under John Ridgely’s tenure, the Northampton Furnace had ceased operations leading to Hampton becoming primarily an agricultural and domestic plantation, rather than industrial. Fewer enslaved workers attempted to seek their freedom during this period, as opportunities for potential free employment in Baltimore or Pennsylvania had also diminished. When enslaved people did attempt seeking their freedom, John Ridgely usually advertised in the press, offered rewards, hire human traffickers, and file affidavits and grants of power of attorney with Pennsylvania courts to return the enslaved people.

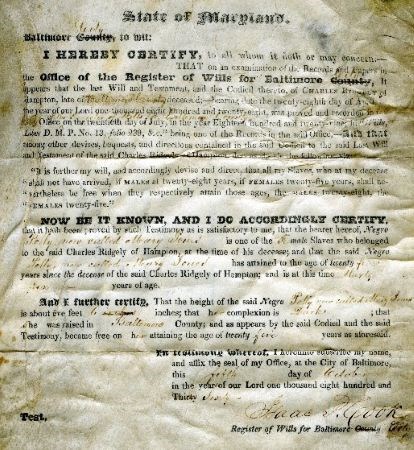

NPS Harsher laws and more comprehensive efforts on the part of enslavers meant that free Blacks were often detained, questioned, and threatened with return to bondage if they could not document their free status. Mary Jones, for instance, formerly enslaved to Governor Ridgely with the name of “Polly,” had to petition for her certificate of freedom as late as 1860, even though she had been freed for eleven years. The number of attempts to find freedom increased during the Civil War. Henry Jackson, Bill Matthews, Charley Buckingham, and Josh Horner fled in May 1861. Henry Jackson’s mother, Lucy Jackson followed suit soon after and Nelson Hawkins left in 1863. By early 1864, the number of enslaved individuals at Hampton had dropped from 61 to 49. Slavery ended at Hampton when Maryland banned slavery on November 1, 1864. Freedom Seekers

Learn More

|

Last updated: September 4, 2025