GRTE/Tobiason Today, geoscientists recognize the fault along the eastern margin of the range. This fault is a crack in the earth's crust due to tectonic forces. The Teton fault is a "normal" fault caused by regional stretching and extends down into the earth's crust at about a 50 degree angle dipping off to the east. With stretching, the two blocks of rock hinge past one another - one tilting skyward, one downward - generating earthquakes as they move. Each movement results in about 1 to 3 feet up for every 4 to 12 feet down. Hundreds of earthquakes over millions of years has lifted the range, even as erosion wears it down. If we could drill a hole through all of the sediments and sedimentary rock in the valley, and find the same layer of sandstone found on the top of Mount Moran, that sandstone would be buried about 20,000 feet. Therefore the Teton fault has moved over 25,000 feet in less than 10 million years.

GRTE/Gilmore Fault ScarpWhen the two blocks of crust slip past each other generating an earthquake, the crack may break through the earth's surface. The break is usually near vertical, and may be up to 20 feet vertical feet. This break is called an escarpment or scarp for short. With time, the sharp top edge erodes and rounds off making a ramp from the bottom to the top of the scarp. Geoscientists map out these breaks in the surface to determine the location of past earthquakes.

USGS - J. Delano, Mark Zellman Trench WorkIn addition to earthquake location, fault scarps can provide information about the timing and size of past earthquakes. Geoscientists dig trenches across scarps, and map out the sediment layers broken by the fault. The amount of offset between sediment layers is related to the size or magnitude of the earthquake. Carbon-14 analysis of organic matter in the layers allows scientists to estimate the age of past earthquakes.Ongoing research on the Teton fault currently records three earthquakes in the past 10,000 years ranging in magnitude from M6.6 to M7.2. The oldest event was about 10,000 years ago, the second one about 8,000 years ago, and the most recent one about 5,900 years ago. The dramatic trench dug at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort in 2017 captures the imagination. Smaller trenches dug around Leigh Lake by hand may seem insignificant, but can provide valuable earthquake data. Stay tuned! The results of some trenching field studies have yet to be published...

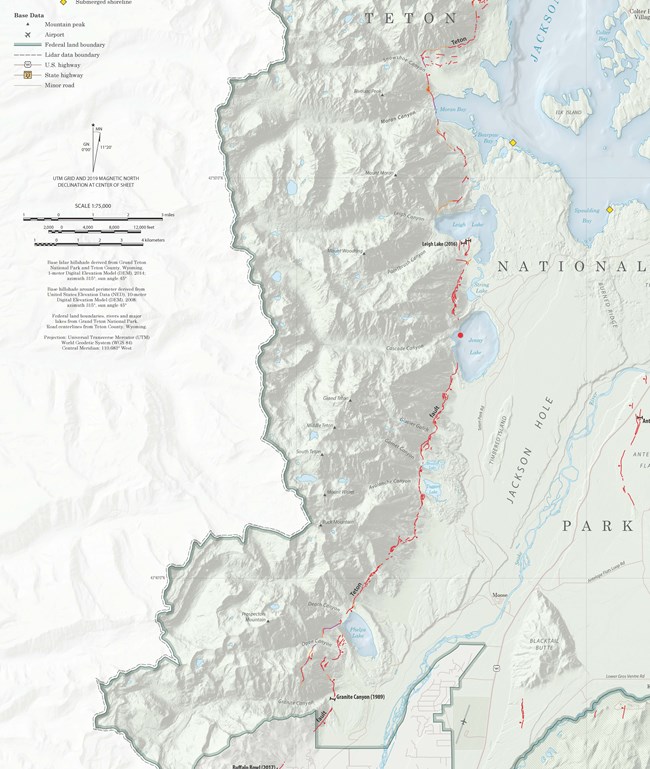

Zellman, M.S., DuRoss, C.B., and Thackray, G.D., 2019, The Teton fault: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 2019-1, scale 1:75,000. Teton Fault MapIn Grand Teton National Park, the understanding of the Teton fault has evolved with time. From crude estimates of where the fault broke the surface to extemely detailed mapping using a process called Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) geoscientists have created very accurate maps of the Teton fault.The most recent fault map for the Jackson Hole valley highlights the Teton fault along the eastern edge of the Teton Range (the redlines on the map). East of the main fault, several small faults break through the surface in the Antelope Flats area. All faults on this map are considered "active" faults meaning that the fault has generated an earthquake within the past 10,000 years - the end of the Pleistocene Ice Age. Less than 10 million years ago stretching generated many cracks across the area. Some cracks may have only generated a few earthquakes and then went dormant. Buttes in the valley such as East and West Gros Ventre buttes are essentially mini-Teton Ranges. Eventually most of the energy focused on one crack becoming the Teton fault. Even now the Teton fault splits at the south end of Jackson Hole just north of Teton Pass. One fault strand runs below Phillips Ridge at the valley floor, and one strand runs below Mount Glory and Little Tuckerman's bowl.

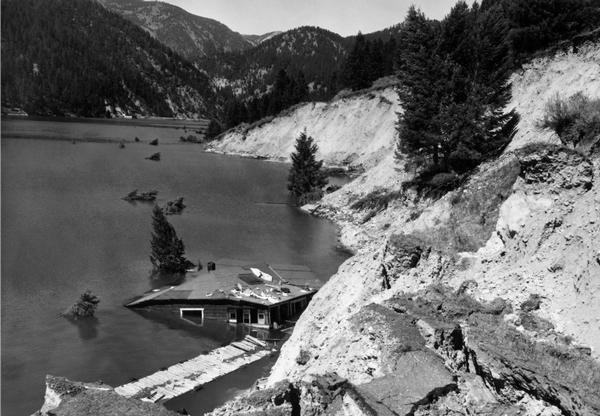

Public Domain Future?The last time a major earthquake rattled the Teton Range and broke the Earth's surface was more than 5,000 years ago. Geological evidence indicates that earthquakes have occurred every two or three thousand years in the past. Are we overdue? Currently, geoscientists cannot predict earthquakes. Truly, a million-dollar geology mystery!What could we expect if an earthquake happened? The Teton fault is capable of generating earthquakes up to a magnitude M7.2-7.5. An earthquake of this size would be similar to the M7.3 Hebgen Earthquake of 1959 outside of West Yellowstone, MT. The ground broke up to 20 feet (6 meters), ground shaking caused the massive landslide that dammed the Madison River creating Earthquake (Quake) Lake, and geysers in Yellowstone National Park changed their eruption frequencies.

GRTE/Adams More InformationVisit Discover Grand Teton for an overview of many natural forces including geology. |

Last updated: May 6, 2020