|

Humpback chub are a threatened species of fish endemic to the Colorado River basin, with the largest remaining population in the world found in Grand Canyon National Park. The main spawning area that sustained the Grand Canyon population following dam construction is in the Little Colorado River. Humpback chub are specifically adapted to the unique characteristics of the Colorado River-high turbidity, and seasonally variable flows and temperatures. Significant threats to humpback chub survival in the Grand Canyon remain, including the presence of invasive fishes and introduced parasites, altered temperature and flow regimes, as well as the potential for large-scale disturbance in their main spawning site. In 2009, the National Park Service and its partners began a project to translocate juvenile humpback chub from the Little Colorado River to other Grand Canyon tributaries. These translocations are part of a comprehensive conservation effort to help ensure that this native fish continues to survive in the Grand Canyon. Tributary translocations have led to satellite spawning populations of humpback chub in Havasu Creek and enhanced survival to augment the number of humpback chub that live in the mainstem Colorado River. The project is funded by the National Park Service and the Bureau of Reclamation, and is currently being conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Arizona Game and Fish Department, US Geological Survey, and Utah State University. A Colorado River Native

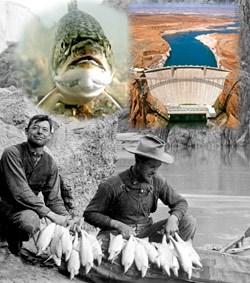

George Andjreko, AZ Game & Fish The humpback chub (Gila cypha) is an unusual-looking member of the minnow family that is endemic, or native, to the Colorado River basin. These fish, which can live as long as 30 years and reach lengths of almost 20 inches, are characterized by large fins and pronounced humps behind the heads of adults.

A Species at Risk

Relatively little is known about the population of this fish in Grand Canyon prior to the closure of Glen Canyon Dam. The humpback chub was first listed as an endangered species in 1967 and currently is protected under the Endangered Species Act as a threatened species. The decline in the humpback chub populations is due to a variety of significant human-caused changes to aquatic habitat in the Colorado River basin. The Little Colorado River

Historically, humpback chub would have used other tributaries besides the Little Colorado River, but currently may be excluded from such tributaries due to competition and predation by invasive fish species. Successful translocations of humpback chub within the Little Colorado River into previously unoccupied habitat above a set of barrier falls set a precedent for potential successful translocations in other Grand Canyon tributaries that provide suitable habitat. Tributary Translocations

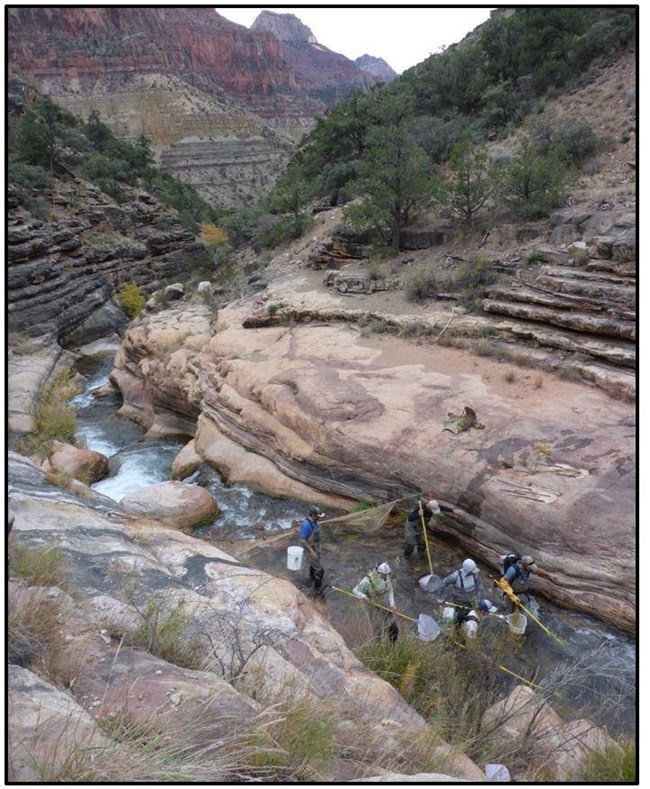

Prior to the translocations, researchers identified the Grand Canyon tributaries most likely to support humpback chub. Tributaries were evaluated on the basis of water quality, temperature, flow, fish barriers, and proximity to the reaches of the Colorado River where wild humpback chub are found. Baseline surveys of existing fish populations were also completed in each tributary prior to translocation. Havasu, Shinumo, and Bright Angel creeks were identified as the Grand Canyon tributaries most suitable for humpback chub. Invasive rainbow and brown trout were removed via electro-fishing and angling from Shinumo Creek (which has only rainbows above the barrier falls near its confluence) and Bright Angel Creek in order to reduce potential predation on the translocated humpback chub. The humpback chub that were released in Shinumo, Havasu and Bright Angel creeks were collected the previous years from the Little Colorado River as juveniles, flown out of the canyon via helicopter, and driven to the Bubbling Ponds Native Fish Facility (operated by the Arizona Game and Fish Department in Cornville, Arizona) or to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Southwestern Native Aquatic Resources & Recovery Center, in Dexter, New Mexico. There, the fish were treated to remove parasites and kept overwinter. Prior to translocation they were given flow training to reacquaint them to river life, weighed and measured, and implanted with unique PIT (passive integrated transponder) tags to individually identify them and track their growth, movement, and survival. On translocation day, humpback chub were flown via helicopter to the release sites in Shinumo, Havasu and Bright Angel Creeks where they were acclimated to creek water and released.

Havasu Creek

Fisheries biologists completed a baseline survey in Havasu Creek in 2010; native bluehead suckers and speckled dace were captured along with a few invasive rainbow trout. While no humpback chub were found during the 2010 survey or in previous surveys, eight mature humpback chub were captured in Havasu Creek just prior to the translocation of juveniles in June. It is unknown whether these wild fish were spawned in the river or in the creek itself, but biologists suspect they arrived from the mainstem during high Colorado River flows in 2011 that inundated a potential barrier near the mouth of Havasu Creek.

On June 28, 2011, 243 juvenile humpback chub were translocated to Havasu Creek in the first of a series of planned releases to take place from 2011-2016. Through hoop-netting recapture efforts, the survival and growth rates of the translocated chub were determined to be comparable to those in the Little Colorado River, indicating habitat was suitable for these new residents. Shinumo Creek

One of the most important features of Shinumo Creek for the translocation project is the presence of barrier falls just above its confluence with the Colorado River. The 15 feet (5 m) waterfall isolates acceptable humpback chub habitat in Shinumo Creek from invasive predatory fishes in the Colorado River. Before the Galahad Fire and subsequent ash-laden flood in 2014 that likely extirpated bluehead sucker and humpback chub, Shinumo Creek had dense vegetation along the shoreline and a good abundance of aquatic and riparian invertebrates. Upstream of the fish barrier, two species of native fish, speckled dace and bluehead suckers, and only one invasive species, rainbow trout, were found. Native fish were more abundant than rainbow trout.

Preceding the fire, a total of 1,102 humpback chub were translocated to Shinumo Creek. The translocations began in 2009, when 302 young chub were released into the creek marking the historic first translocation of humpback chub within Grand Canyon National Park. Data collected during monitoring efforts between 2010 and 2014 assessed the annual survival, growth, and movements of translocated humpback chub. Annual growth rates of translocated humpback chub in Shinumo Creek were comparable to, or higher than growth rates in either the Little Colorado River or the Colorado River. Some humpback chub released in Shinumo Creek reached minimum spawning size after only two years, which usually happens at three to four years of age. The next milestone for the Shinumo population would have been the observation of spawning behavior or the capture of untagged juvenile fish. Many translocated fish that left Shinumo Creek have been found living in the Colorado River. Through 2019, biologists from the NPS, Grand Canyon Research and Monitoring Center,U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Arizona Game and Fish Department have re-captured more than 20% of chub from the Shinumo translocations in the Colorado River or Little Colorado River, suggesting that translocations may increase the overall Grand Canyon humpback chub population.

The Galahad Fire, started by lightning in May 2014, burned approximately 6500 acres and 10% of the Shinumo watershed. Biologists reported the Colorado River had turned dark with ash and smelled like a campfire downstream of Shinumo Creek. Charcoal pieces were also observed in the creek. In September, NPS monitoring revealed severe flood disturbance & widespread deposition of charred wood with the water level appearing to have risen at least 12-15 feet above baseflow. Riparian vegetation was reduced by approximately 80-90% and macroinvertebrate densities and taxa richness significantly reduced. Sediment deposition eliminated most pool habitat, including former humpback chub translocation sites. The fish community was determined to be reduced by 99%. Humpback chub and bluehead sucker likely remain extirpated from the Shinumo Creek watershed upstream of the falls in 2021.

The NFEC program is currently assessing the habitat conditions in Shinumo Creek to determine the feasibility of possible future translocations and reestablishment of bluehead sucker. In July and September in 2020 and 2021, biologists conducted hoop-net monitoring in lower Shinumo Creek (below Shinumo Falls) and its inflow reach in the Colorado River. The NFEC program found young-of-year humpback chub in the mouth of Shinumo Creek in September, 2020, indicating reproduction may be occurring.

Bright Angel Creek Trout Reduction Project and Humpback Chub Translocation

Biologists are using two methods for capturing and removing invasive trout throughout Bright Angel Creek during the winter months: a weir, or fish trap, and electro-fishing. The weir captures large trout that live in the Colorado River as they enter Bright Angel Creek to spawn. Electro-fishing allows fisheries biologists to monitor and assess the fish population of the creek, and also remove invasive trout while safely releasing native species that live in the stream. This project is funded by the Bureau of Reclamation and National Park Service, with staff contributions by the NPS, American Conservation Experience, and a large number of volunteers.

Native and Invasive Fish in Bright Angel CreekAt least five of Grand Canyon's eight species of native fish were historically found in Bright Angel Creek. The creek was likely an important spawning location for several species. Today, native flannelmouth and bluehead suckers, as well as speckled dace still spawn in Bright Angel Creek each spring. Humpback chub were first scientifically described from specimens collected in or near Bright Angel Creek. Over the last 100 years and prior to trout removals, the numbers of native fish in Bright Angel Creek declined while the numbers of invasive species have increased. Robust populations of native fish are important indicators of an aquatic ecosystem's overall health. National Park Service Management Policies (2006) require that species and natural ecosystems are preserved, invasive species including trout are removed when feasible, and that recovery actions are taken when park resources have been damaged or compromised. A variety of laws, including the Endangered Species Act, require the protection of rare or endemic species in National Park Service units. The Bright Angel Creek Trout Reduction Project is part of a larger effort to restore habitats and native fish throughout the park. Trout species are not native to the Grand Canyon (the Colorado River Basin has a native cutthroat trout, but it is found only in high-elevation streams upstream of present-day Lake Powell). Brown and rainbow trout were stocked in the Grand Canyon’s Colorado River tributaries in the first half of the last century before the existence of current environmental regulations and development of ecological knowledge of aquatic systems. Prior to removals, brown trout, a species native to Europe and Asia, were the most common fish species found in Bright Angel Creek. As recently as the 1970s, brown trout were rare in Bright Angel Creek. Along with the increase in the number of brown trout in Bright Angel Creek since the 1990s, there was a corresponding decline in native fish. Studies in Bright Angel Creek and in the Colorado River showed that much of the diet of brown trout in Grand Canyon consists of fish, and they preferentially consume native fish. Hence, the presence of brown trout likely has had significant impact on the native fish population in the Colorado River and Bright Angel Creek. Invasive Trout Removal

The purpose of the Bright Angel Creek Trout Reduction Project is to benefit threatened humpback chub and other native fish species in the Colorado River, and to restore and enhance, to the extent possible, the native fish community that once flourished in Bright Angel Creek. Grand Canyon fisheries biologists are using two approaches to achieve these objectives: a fish weir and backpack electro-fishing to remove trout, and translocations of humpback chub.

Electro-fishing is a non-lethal method for capturing fish and is used extensively by fisheries biologists to monitor fish populations in streams. In Bright Angel Creek, crews electro-fish upstream of the weir in late October and late January. Electro-fishing allows biologists to selectively remove trout, and to monitor responses of the native fish community to invasive fish removal.

TranslocationsFollowing this successful suppression of invasive trout in Bright Angel Creek, native fish populations increased by over 400%, and young flannelmouth suckers were observed rearing in the creek for the first time since brown trout came to dominate the creek. The NFEC program completed the 2nd of 5 planned translocations of threatened humpback chub in June 2020. The goal of humpback chub translocations is to establish self-sustaining reproducing populations in tributaries with seasonally-warm and naturally fluctuating flow and thermal regimes. Bright Angel Creek differs from other translocation creeks (Havasu and Shinumo) Creeks, in that no barrier exists to prevent fishes from moving back and forth from the Colorado River.To understand these movements, including spawning movements and emigration of translocated fish, a PIT-tag antenna system was installed near Phantom Ranch. The antenna system has provided valuable information about immigration of fish from outside of Bright Angel Creek, revealing potential spawning runs by adult, non-translocated humpback chub, as well as by hundreds of flannelmouth and bluehead suckers. It has also documented repeat spring and summer use of the creek by translocated humpback chub that have emigrated to the mainstem. Invasive trout that were tagged throughout the Colorado River in Grand Canyon and Glen Canyon below the Dam have also been detected. Bright Angel Creek AnglingAnglers visiting Phantom Ranch can expect to encounter fewer trout in Bright Angel Creek. No bag limit for brown or rainbow trout is in effect for Bright Angel Creek. Anglers are encouraged to keep and enjoy the trout they catch.For questions and comments about the Bright Angel Trout Reduction Project, please contact Grand Canyon National Park's Fisheries program at (928) 638-7453 or (928) 638-7477, or via email here.Project CooperatorsU.S. Bureau of Reclamation Learn MoreCanyon Sketches Vol 12 - August 2009 300 Humpback Chub Translocated into Shinumo Creek On June 15, 300 young humpback chub were translocated from the Little Colorado River to Shinumo Creek in order assess the feasibility of establishing an additional population of this endangered species in a Grand Canyon tributary. Visit the Canyon Sketches eMagazine Home Page.

Canyon Sketches Vol 23 - September 2011 2011 Humpback Chub Translocations to Havasu and Shinumo Creeks In June 2011, Grand Canyon National Park took another major step in the effort to restore native fish populations in the Grand Canyon with the release of 243 juvenile humpback chub into Havasu Creek. Translocations to tributaries may establish additional spawning populations of this endangered species in Grand Canyon or add to the number of humpback chub living in the Colorado River. Native Fish Ecology and Conservation

|

Last updated: February 16, 2022