|

During the American Revolution a small earthen star fort known as Fort Whetstone was constructed at the end of the peninsula that led to the entrance of the Baltimore harbor. Although the fort was never attacked during the American Revolution, military experts saw the importance of coastal defenses around the young United States’ third largest city and one of its vital ports. In 1798 construction began to expand upon Fort Whetstone with brick and stone masonry to create a new, more permanent, structure. The new fort was dubbed Fort McHenry, named after George Washington’s Secretary of War, and Baltimore native, James McHenry.

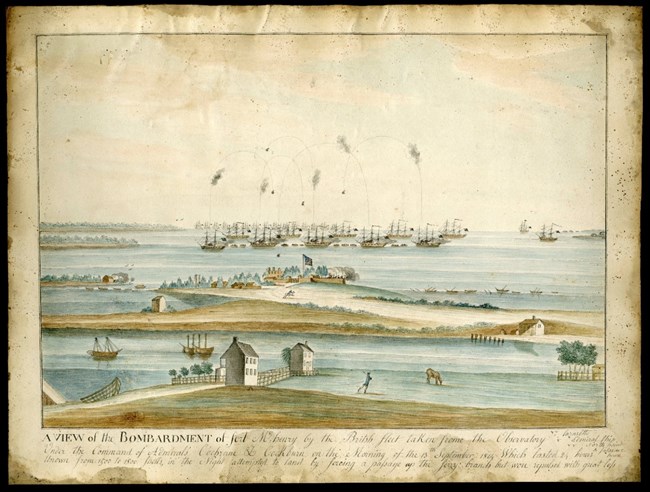

NPS The War of 1812After its completion in 1803 Fort McHenry had a brief period peace which allowed the fort to be an outpost for the small standing army of the United States, and the country’s first light artillery unit was organized there. On June 18, 1812 the United States declared war on England following several disputes around “Free Trade & Sailor’s Rights.” Fort McHenry’s role became even more vital in 1813 when British forces entered the Chesapeake Bay and began a campaign of terror in the region. In August of 1814 disaster struck the American forces when they were humiliated at Bladensburg and British forces captured and burned Washington D.C.

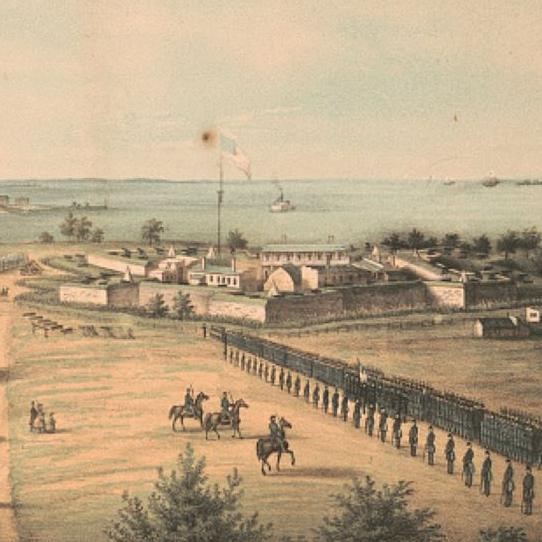

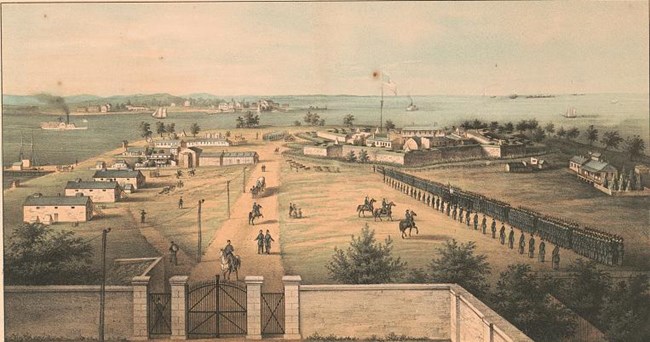

Library of Congress The Civil War (1861-1865)In the years that followed the War of 1812, Fort McHenry went through a series of changes and improvements. Buildings were expanded, outer defenses were added, and an Army colonel by the name of Robert E. Lee oversaw the construction of Fort Carroll to add to Baltimore’s coastal defenses. When Civil War broke out in 1861, Fort McHenry’s defensive role was once again prominent, with its large cannons not only pointed towards the water to defend the city from coastal attack, but also pointed towards the center of Baltimore to intimidate its pro-secession population into remaining in the Union.

NPS 20th CenturyFollowing the Civil War, Fort McHenry declined in strategic importance. Its structures and defenses were outdated for modern machines of war. However, when the United States entered the First World War in 1917 the site found new purpose. The grounds surrounding the fort were transformed into a massive 100 building and 3,000 bed hospital. General Hospital No. 2, as it was called, existed from 1917 to 1925, and marked the busiest time period in Fort McHenry's history.

|

Last updated: January 29, 2026