Visit With Our Partners

Heritage Tourism at Ebey's Reserve: "Hands on History"Discover the rich cultural and historical experiences that await at Ebey's Landing National Historical Reserve. Embrace "Hands on History" by visiting local landmarks, exploring the charming town of Coupeville, and discovering the natural beauty of Central Whidbey Island's state parks. These unique destinations offer visitors a window into the past and the chance to engage directly with the heritage of the area. For more details about the Reserve and the organizations that help preserve its history, connect with our valued partners. (Please note: external links will take you outside our website.)

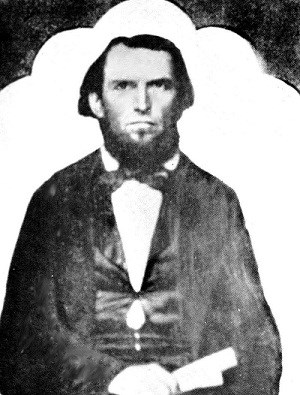

The First Stewards: The Lower Skagit PeopleFor thousands of years, the Lower Skagit People thrived on the shores of Penn Cove, establishing permanent villages and living in harmony with the land. Rich with natural resources, the island provided an abundance of salmon, bottom fish, shellfish, berries, small game, deer, and waterfowl. The Lower Skagit People skillfully managed the prairies through practices such as selective burning, transplanting, and mulching to encourage the growth of bracken fern, camas, and other favored root crops. By the time European explorers arrived in the late 18th century, Central Whidbey Island had been shaped by over 12,000 years of continuous human habitation. In 1790, records show more than 1,500 Indigenous People living on the island, their lives deeply connected to its rich ecosystems. However, the arrival of settlers brought profound and lasting change. In 1855, the Lower Skagit People, along with other Coast Salish Tribes, were compelled to sign the Point Elliott Treaty. This treaty removed them from their ancestral lands and relocated them to what is now the Swinomish Tribal Community in La Conner. Today, Ebey’s Landing National Historical Reserve acknowledges Central Whidbey Island as the homeland of the Lower Skagit People, honoring their enduring connection to this land and their contributions to its history. Charting the Course: Vancouver’s Legacy on Whidbey IslandIn 1792, Captain George Vancouver named Whidbey Island in honor of Lieutenant Joseph Whidbey, who conducted detailed explorations of the island during their expedition. Vancouver’s widely shared accounts of Puget Sound captured the imagination of settlers and paved the way for white settlement in the region decades later. A critical driver of this migration was the Donation Land Law of 1850, which promised free land in the Oregon Territory to white citizens willing to homestead it for four years. Drawn by the fertile prairies of Central Whidbey Island, settlers arrived in growing numbers, claiming lands already inhabited and cultivated by the Lower Skagit People. They carved out irregular claims shaped by the natural contours of the land, prioritizing the most fertile areas for farming. Today, this early settlement pattern endures as part of the landscape. Fence lines, roads, and ridges in Ebey’s Reserve continue to reflect the choices and impact of those early settlers, preserving a visible link to the past. Letters Home..."My dear brother— I scarcely know how I shall write or what I shall write . . . the great desire of heart is to get my own and father's family to this country. I think it would be a great move. I have always thought so . . . To the north down along Admiralty Inlet . . . the cultivating land is generally found confined to the valleys of streams with the exception of Whidbey's Island . . . which is almost a paradise of nature. Good land for cultivation is abundant on this island. I have taken a claim on it and am now living on the same in order to avail myself of the provisions of the Donation Law. If Rebecca, the children, and you all were here, I think I could live and die here content." ~ Colonel Isaac Ebey, letter to his brother, W.S. Ebey, Olympia, Oregon, April 25, 1851 Colonel Isaac Neff Ebey’s heartfelt letter captures the allure of Whidbey Island in the mid-19th century. The island’s fertile land, stunning beauty, and promise of opportunity compelled Ebey to leave his home in Missouri to establish a claim under the Donation Land Law of 1850. His vision of Whidbey as “almost a paradise of nature” reflects not only the abundance of the land but the hope it inspired in settlers. Today, his legacy lives on in the Reserve that bears his name, preserving the prairie and farmlands that first drew him to Central Whidbey Island.

Island County Historical Society The Ebey FamilyColonel Isaac Neff Ebey was among the first of the permanent settlers to the island. Upon the advice of his friend Samuel Crockett, Ebey came west from his home in Missouri in search of land. Both men had filed donation claims on central Whidbey by the spring of 1851. Ebey wrote home, enthusiastically urging his family to join him. Ebey's family soon emigrated to the island. The simple home of Isaac's parents, Jacob and Sarah, and a blockhouse erected to defend his claim against unfounded Indian agression, still stand today overlooking the prairie that bears the family name. As for Isaac, he became a leading figure in public affairs, but his life was cut short with his death in 1857. Today some farmers of Central Whidbey still plow the homeland of the Lower Skagits, and the donation land claims established by their families in the 1850s, preserving a historic pattern of land use centuries old. Fertile free farmland was not the only incentive to white settlement. Sea captains and merchants from New England were drawn to the protected harbor of Penn Cove and the stands of tall timber valued for shipbuilding. Many brought their families and took up donation claims along the shoreline. One colorful seafaring man was Captain Thomas Coupe, who startled his peers by sailing a full-rigged ship through treacherous Deception Pass on the north end of the island. In 1852, Coupe claimed 320 acres which later became the town of Coupeville on the south shore of the cove. The success of white settlement and Central Whidbey's farming and maritime trade transformed Coupeville into a dominant seaport. Visitors to Central Whidbey Island and the town of Couepville can still see many 19th-century false-fronted commercial buildings along Front Street, its historic wharf and blockhouse, and a collection of Victorian residential architecture. Military HistoryThe United States military added a significant chapter to the story of Central Whidbey Island with the construction of Fort Casey Military Reservation in the late 1890s. Positioned strategically on the bluff above Admiralty Head, Fort Casey was part of a three-fort defense system designed to safeguard the entrance to Puget Sound. The first U.S. Army troops arrived at Fort Casey in 1900, with personnel numbers eventually reaching 400. Beyond its military purpose, the fort became a social hub for the local community, hosting ball games, dances, and other events that brought soldiers and civilians together. Today, visitors can explore remnants of the fort's history, including its impressive gun escarpments, the Admiralty Head Lighthouse, and the preserved wood-framed officers' quarters. World War II and BeyondThe military presence on Whidbey Island expanded during World War II, leaving a lasting impact on the region. Near the northern boundary of Ebey’s Reserve lies Fort Ebey, a remnant of the defensive build-up during this critical period. Further south, along Highway 20, travelers encounter the Outlying Field (OLF), established during World War II to train pilots. Initially used for propeller fighters and later for jet fighters, the OLF remains active today as part of Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, where pilots continue to train for combat missions. |

Last updated: November 22, 2024