NPS Photo Take Pictures for ScienceThe Denali Alpine Wildlife Project offers citizen scientists a way use photographs to understand whether and how alpine wildlife are being affected by climatic and vegetation changes. To determine how these changes might affect them, researchers in the park are trying to understand what kinds of habitat each animal needs—in short, where different animals live and why. Farther south in North America, the American pika is a ‘canary in the coal mine’ for climate change—it is very susceptible to warming and has been lost from many areas where it once occurred. But for its relative in Alaska, the collared pika, we do not yet know whether these changes are a threat. Alpine wildlife may be particularly at risk due to both the changing climate and the rapid expansion of tall shrubs and trees into the alpine tundra. The Denali Alpine Wildlife Project is a park-wide survey of alpine wildlife species through the University of Montana. Public participation is purely voluntary. We are building a database of wildlife sightings (i.e., photographs) through iNaturalist, a free and easy to use app that records the date, time, and location of submissions. iNaturalist accepts photographs of plants, wildlife, and scat.

Don’t want to use an app to record data? Please feel free to email your high-quality photographs (with GPS locations) to us! Before you start your trip:

During your trip:

Note: We are also interested in sightings of willow, rock, and white-tailed ptarmigan. If you are an experienced birder and are able to differentiate between these three species, please submit any sightings to eBird. This project requires you be physically in Denali National Park & Preserve. While in the park, look anywhere you wish, but especially at high elevations away from maintained trails.

Pay attention to talus areas. These are rocky outcrops with shoebox- to truck-sized rocks, and will be your go to spot for finding pikas and marmots! Look out for scat! Finding and identifying animal excrement (‘scat’) can be a great way to record data on our study species even if you don’t see the animals. High-quality scat photographs (i.e. in focus and clear) can be submitted to iNaturalist. Make sure there is something in the photograph for scale, like a pocketknife, coin, or car key. See the "Identifying Scat" section, below, for more details. The research team behind this project would love to hear about your experiences in collecting data for the Denali Alpine Wildlife Project. How many miles did you hike? What animals did you see? Did collecting data affect your experience in the park? Please send the research team a message!

Data provided by the public are critical to the success of the Denali Alpine Wildlife Project. Park service biologists and their scientific collaborators are really grateful for your help! Return to top of the page

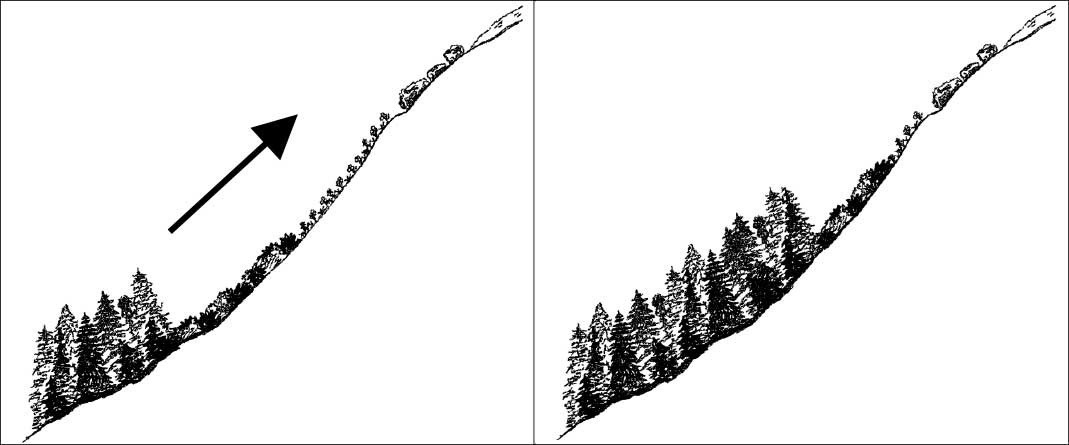

Alex Mateik Project BackgroundOur climate is changing rapidly, and we see examples of this around the world through increasing temperatures, changing rainfall patterns, and increasingly frequent and strong storm events. These changes are particularly serious in Arctic regions, which are experiencing temperature increases at almost twice the rate of the rest of the world. Increasing temperatures are melting glaciers and snow and thawing permafrost, and these changes cause the organisms living in the Arctic to change in response.For example, if you look at the vegetation going up a mountain, you can see a shift from trees to shrub to tundra to rocks to snowcapped peaks. But, as weather patterns change, we are seeing trees moving up into where the shrubs are and shrubs moving into the tundra, in what are known as high alpine environments.

The Denali Alpine Wildlife Project’s goal is to research how both changing climate and shifting vegetation are impacting where alpine wildlife live in order to predict where they might live in the future as their environment continues changing around them. We are focusing specifically on wildlife living in high alpine environments in Denali.

Jedediah Brodie Identifying ScatFinding and identifying animal excrement (‘scat’) can be a great way to record data on our study species even if you don’t see the animals. High-quality scat photographs (i.e. in focus and clear) can be submitted as part of this citizen science project. Make sure there is something in the photograph for scale, like a pocketknife, coin, or car key. In rocky talus, look for scat wherever you see bright orange lichen (Xanthoria lichen) on the rocks, as it often grows in areas where animals repeatedly urinate and defecate.

Jedediah Brodie Pika ScatCollared pika scat looks just like rabbit scat – round and flattened – only much smaller. Each pellet is about 0.1 inches (3 mm) across. Pellets can be found individually or in piles.

Jedediah Brodie Arctic Ground Squirrel ScatArctic ground squirrel scat is larger than that of pikas, about 0.4 inches (10 mm) long. It is generally irregularly shaped and is often in clumps of two or more pellets together.

Government of Yukon Marmot ScatHoary marmot scat is larger that that of Arctic ground squirrels, about 2.5 inches (6 cm) long by 0.8 inches (2 cm) wide. It is in irregularly shaped pellets or tubes.

Jedediah Brodie Dall Sheep ScatDall sheep scat is regularly shaped, oval pellets (like those of domestic sheep or goats), about 0.8 inches (20 mm) long. These are always found in piles, either where the animals were grazing (ex. in meadows and tundra), or where the animals bedded down (on the tundra or on rocky outcrops).Snowshoe Hare ScatSnowshoe hare is not one of this study's species, but their scat could be confused with that of our study species. Hare scat is the same shape as pika or rabbit scat—round and flattened—but much larger than pika scat: about 0.4 inches (10 mm) across. It is the shape and roughly the size of an M&M candy. Pellets can be found singly or in small piles. |

Last updated: August 10, 2023