Viewpoint

Gauging Community Values in Historic Preservation(1)

by Dirk H.R. Spennemann

Shakespeare's line, "What is past is prologue," spoken by Antonio in The Tempest sets the scene for this article. The achievements of our past set the scene for future actions or reactions in the political, social, and economic arenas, just as much as the past of our profession provides the foundation for the future of our discipline.

All historic preservationists agree that the preservation of the tangible expressions of the past, or at least significant elements of the past, is deemed desirable, and because of this agreement, it has been mandated by international charters (World Heritage Convention) and national and state legislation such as the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) in the United States and the Heritage Act in New South Wales, Australia.(2) Just as there is no need to revisit the nature of this agreement, there is not much need to look at the question of who owns the past since the need to ensure that stakeholders are adequately represented and differential levels and, on occasion, the primacy of "ownership" are acknowledged in the management process.(3)

More relevant is the question, "which past do we preserve?" As David Lowenthal has demonstrated, there are a multitude of pasts, and the past we tend to preserve is often the sanitized one, the safe and comfortable one; the past that we can visit akin to a foreign country, safe in the knowledge that, should we suddenly feel uncomfortable, we can return to the present.(4) Dissonant heritage places such as sites of trauma and atrocity are frequently managed through active neglect or through memorialization after removal.(5) We still struggle on occasion to find a balance.

For Whom Do We Preserve the Past?

There can be no doubt that as historic preservationists we actively interfere with the processes of change. Our actions range from the intervention in environmental decay through physical conservation projects, to intervention in building renewal and replacement by protecting single properties from demolition, to declaring historic precincts at the planning level.(6) Some of that kind of intervention is regulatory, through heritage listings and conservation instruments, and some is incentive-based, through tax credits or conservation grants.(7)

The question we have to ask is for whom do we preserve this past? It is commonly asserted that the preservation of the past is done for the benefit of future generations.(8) But, on reflection, is that a valid argument to make? Heritage management has borrowed the terminology of "stewardship" from the arena of natural resource management, with the term prominently used in the title of this publication, CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship. In the natural environment, the term "stewardship" entails the concept that natural resources have been here for a very long time, well before the advent of people, and that each generation of people is entrusted with the management of this environment in a way that it can be handed on to the next generation in the same or better state than it was found—with the underlying notion of the interdependency of human existence and the natural environment in which the former is grounded. By that notion we are not owners of the land, but mere custodians and stewards. While the ecological meshing of natural environment and human existence can be demonstrated, we need to question whether the same concept can be uncritically applied to the cultural environment.

Let us consider for a moment the underlying four axioms for historic preservation. Heritage places are scarce, finite, nonrenewable, and valuable.(9) It is the last axiom that is significant in this context: Heritage places are valuable. But objects, places, and resources have no intrinsic value per se. Individuals project value onto an object, place, or resource based on their own needs and desires, shaped by their current social, cultural, and economic circumstances, which in turn are informed, and to a degree predisposed, by an individual's personal history of experiences, upbringing, and ideological formation.

Individuals hold different values with varying strengths of conviction. Subjective valuation, revaluation, and ultimately prioritization occur consciously and subconsciously on a continual basis. If a choice has to be made, individuals tend to be prepared to "trade-off" one value against another. These decisions will change with individual circumstances and are subject to change over time.(10) This fluidity of projected values, both on an individual and a collective level, with continuously shifting ground rules, needs to be acknowledged.(11) Clearly, values are mutable, and heritage places that may be evaluated as insignificant today may be regarded as significant tomorrow. It is assumed, without either justification or reflection, that sites that are already included on a register will remain significant. This assumption is spurious, as by its very nature the concept of a mutability of heritage values works both ways.

Is our preservation intervention for the benefit of our children's children, as we make believe, or is it for our own benefit in the present? Since we cannot predict the values that may be held by our children in the future, let alone by their children, any assumption that we preserve the places for future generations to enjoy is without solid foundation. Just as we criticize the actions of the generations that went before us, deploring environmental degradation or the loss of building fabric, so will we be judged by future generations on how we have managed our present, their past.

It follows, inevitably, that we are preserving the past according to our present values and essentially for our own benefit and that, bluntly speaking, we are shaping the past in the image of our values. If we push this line of thinking further, we may stand accused by future generations of consciously or subconsciously constraining any choices a future heritage manager may be able make; that through the conservation actions (and non-actions) we are taking today we are, in fact, saddling the future with our perceptions of the past. Yet, while we will face future criticism, we can argue at least that we have made educated and conscientious decisions based on current best practice and understanding.

But the rationale for the preservation of our past—that we are doing so in an altruistic fashion for the benefit of future generations—can no longer stand up. We have to face up to the reality that we are doing this for the present, that we are doing this for ourselves. This then forces us to reassess the role heritage places play in our contemporary world.

The Role of Heritage Places in Our World

We preserve heritage places because they form a link with our past. They provide tangible evidence of technical achievements, and they chronicle the development of style and aesthetic beauty. We preserve them because they are localities with tangible remains where events took place that have significantly shaped our history and thus played a role in shaping the present. We preserve places that give us a warm and fuzzy feeling of nostalgia(12) or national pride(13) and that foster national cohesiveness.(14) We also preserve places that are thorns in that pride but the presence of which we need as reminders of events never to be repeated.(15) Heritage places provide us with the tangible reminders of our past, and are localities that, as a collective, describe our identity as a society.

Would it really matter if heritage places were removed? Is historic preservation merely a luxury in times of economic affluence as is frequently asserted by detractors and opponents, especially in developing countries, or is it an integral part of the social and mental well-being of a community?(16) The answer lies in the significance of heritage places to ethnic and cultural identity and in the research conducted on the meaning of, and attachment to, place.

The fact that heritage places are significant expressions of the cultural, ethnic, and spiritual identity of communities across the globe can be demonstrated by the extent to which heritage places have been treated as symbols for a cultural group, and to the extent to which an opposing group has gone in ensuring the destruction of the place. Three examples may suffice. The Buddha statues of Bamyan in Afghanistan are a good example of religious fundamentalism specifically targeting cultural icons,(17) while religious conflict also resulted in the destruction of a 16th-century mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, India.(18) The Mostar Bridge in Bosnia is an example where religious and politically motivated warfare targeted and eventually destroyed a structure inscribed on the World Heritage List. Erected in 1566 by the Turkish architect Mimar Hayruddin, the bridge was an enduring symbol of the Turkish presence in the former Yugoslavia and thus an ideological, more than a military, target of the Bosnian-Serb forces.(19)

But beyond the iconographic heritage places that are imbued with a high spiritual significance, as in the examples above, even non-religious heritage places play a major role in the well-being of a community in general. The psychological profile of our cognitive self seeks out the familiar in our environs, with people developing attachments to places of residence, work, and emotional events.(20) It is that attachment to place that generates some of the social and community values towards heritage places. Studies have shown that communities rebound faster and more comprehensively from a natural disaster if the key features of their physical environment have been less affected,(21) and that the retention of heritage features assists in the regaining of a sense of normalcy.(22) Likewise, communities that have been relocated because their old location is no longer viable because of reservoir flooding, for example, have shown an increased dysfunction unless part of the heritage could be relocated also. Elsewhere, the argument has been made that key cultural heritage places should be regarded as critical infrastructure in the events of disasters and should receive a concomitant level of attention in the disaster response phase.(23)

It can therefore be posited that heritage places are not merely tangible evidence of the past as deemed important to a small, historically-minded subset of society, but that they provide emotional anchors for the community as a whole. Extending this argument, a full understanding of the heritage values of a community could lead to the comprehensive protection and preservation of those properties that are central to the sense of place a community experiences. Such protection, then, is not merely an indulgence by historic preservationists, but the provision of a social and community service.

Consulting the Community

If we consider heritage places as significant to the psychological well-being of community as these places contribute fundamentally to a sense of place and belonging, then it follows that we have to ensure that the community's views are actively sought in the identification of heritage places. And here it is that some of us run into trouble. In theory, a county or local government area-wide heritage study sees heritage places identified and assessed by a range of practitioners in collaboration and consultation with the affected community. Community involvement in the process has long been recognized as crucial as mid- and long-term protection of heritage places can only occur if such places are "embraced" or "owned" by the community. It is the level and nature of community involvement in that process, however, that causes problems for historic preservationists. As always, there are two diametrically opposed solutions, top-down expert-driven studies, and bottom-up community-driven studies. An expert-driven approach tends to underestimate places important to the community, favoring instead types of places the experts are comfortable working with, while a community-driven approach tends to favor "popular" places and overlooks or even actively ignores places that do not fit the community mold.(24)

The historic foundation of the heritage movement in the United States, as is the case in Australia, was rooted in the interests of archeologists, architects, and historians who sought to preserve parts of the nation's heritage for future generations, for archival and demonstration purposes, or for future scientific investigations.(25) Not surprisingly, then, heritage studies were traditionally carried out by a team of experts drawn from these disciplines, and many studies still fall into that mold.(26) The standard heritage study of the 1970s and 1980s would see a small team of specialists descend upon a community and study its history as reflected in its architectural presence. Places were selected for protection based on historic relevance, architectural importance, and aesthetic appeal. Consultation tended to be limited to people seen as knowledgeable in the history of the area and vocal stakeholder groups, such as the historical societies.

During that time, there was little doubt that experts were afforded the authority to make decisions on matters within their purview. After all, it was accepted that the expert had studied the subject matter and thus was qualified to comment, while the average citizen was not. Increased levels of tertiary education, coupled with an increasing environmental consciousness and an increased level of community involvement in other land management issues,(27) saw the wider community assert its authority to speak on matters of cultural heritage. After all, it was their past and their identity that was being decided on.(28) In that regard, the empowerment of the Indigenous Australians and American Indians to influence the destiny of their own heritage cannot be underrated as a stimulus.

From Individuals on the Soap Box to the Majority

At least in the Australian setting, the role of the heritage planner has evolved to that of a facilitator, conducting community workshops and juggling their outcomes with the opinions of specialists in the fields of archeology and history. Even though such approaches are community-focused and on occasion community-driven, the authority commissioning the plan influences the outcomes through the phrasing of the terms of reference, including stipulating who should be regarded as a stakeholder, and through the level of funding allocated to conduct the study, which directly translates into the time consultants can spend on the matter.(29)

Modern heritage management plan development, while controlled by an expert as facilitator, draws on a small group of stakeholders through formal responses to draft documents, through direct one-on-one consultation with individuals or groups, through selected focus groups or through more openly-structured community workshops. Large-scale community meetings have also been held. Community-driven or community-controlled heritage studies, such as those developed in New South Wales,(30) place community members in control, who, assisted by a project manager, and assisted by historic theme studies compiled by a professional historian, select heritage places deemed worthy of preservation.

In the New South Wales scenario, sites outside the predefined historic thematic framework are prone to be overlooked, either consciously or subconsciously (assumed to be outside the parameters) unless the lay committee is prepared to argue the case. Unless the commissioning authority specifically requests the inclusion (or exclusion) of specific stakeholders, the stakeholder selection will be driven by individual responses to public advertisements and calls for expression of interest. This means that self-nomination is encouraged, which will cause the process to be dominated by self-interest groups who may not be representative of the population at large.(31) The more multicultural a community, the more complex this process will be, with political undertones that can only be ignored at peril.(32)

While focus groups and guided survey questions allow one to query in-depth views about heritage, they can, in fact, limit the range of places mentioned simply by subconsciously restricting the view of participants as to what does and what does not constitute a heritage item. A further problem with purely community-developed heritage studies, however, is that some elements of the community's heritage are overlooked as the value to the properties is more obscure and requires expert historic or archeological research to identify them. Other elements of the heritage may be actively, consciously, or subconsciously ignored as they belong to the group of dissonant values.(33)

Even though the above-mentioned processes are infinitely more inclusive than mere expert-driven studies, they do not go far enough. We are still limited to identified stakeholder groups as well as self-appointed preservation advocates. The heritage places we are identifying and protecting still only represent the view of a select group of experts and key stakeholders. The silent majority has not been consulted. There can be no doubt that this group has been given the opportunity to be consulted, and that the majority for whatever reason has decided not to participate. But this non-participation neither invalidates the views the majority may hold, not does it imply that the majority does not hold a view either way. The underlying reasons for the non-participation of the greater proportion of the public in such studies are complex, ranging from disengagement with and mistrust of government to cynicism of the process and feeling that their opinions would not be counted anyway.

As historic preservationists, we must never forget that it is this silent majority that funds much of the historic preservation effort through the taxes paid. Apathy and disengagement with heritage will eventually lead to claims that historic preservation, as it is being carried out today, is no longer congruent with the interests of this silent majority. A severe cut in funding or a weakening of preservation legislation may well follow, either because the silent majority will have embraced other priorities or because it does not see its interests safeguarded by the existing processes.

It is time for the historic preservation discipline to be proactive in the matter, to develop programs that actively seek out the view of this silent majority, and then incorporate, and be seen to incorporate, their view into historic preservation planning and management.

Accessing the View of the Larger Community

If focus groups and community meetings do not elicit sufficient responses and the participation of the wider public, then other means of data collection need to be used, one where members of a community are asked as individuals, outside of a group setting and without external influences and pressures to nominate places of a community's cultural environment that are significant to them personally, and furthermore nominate places that they see as significant to the community as a whole.

This survey can be carried out by sending open-ended anonymous questionnaires to all households(34) or by a representative random sample drawn from the electoral roll.(35) The differences between "normal" community studies and such general approaches are striking.

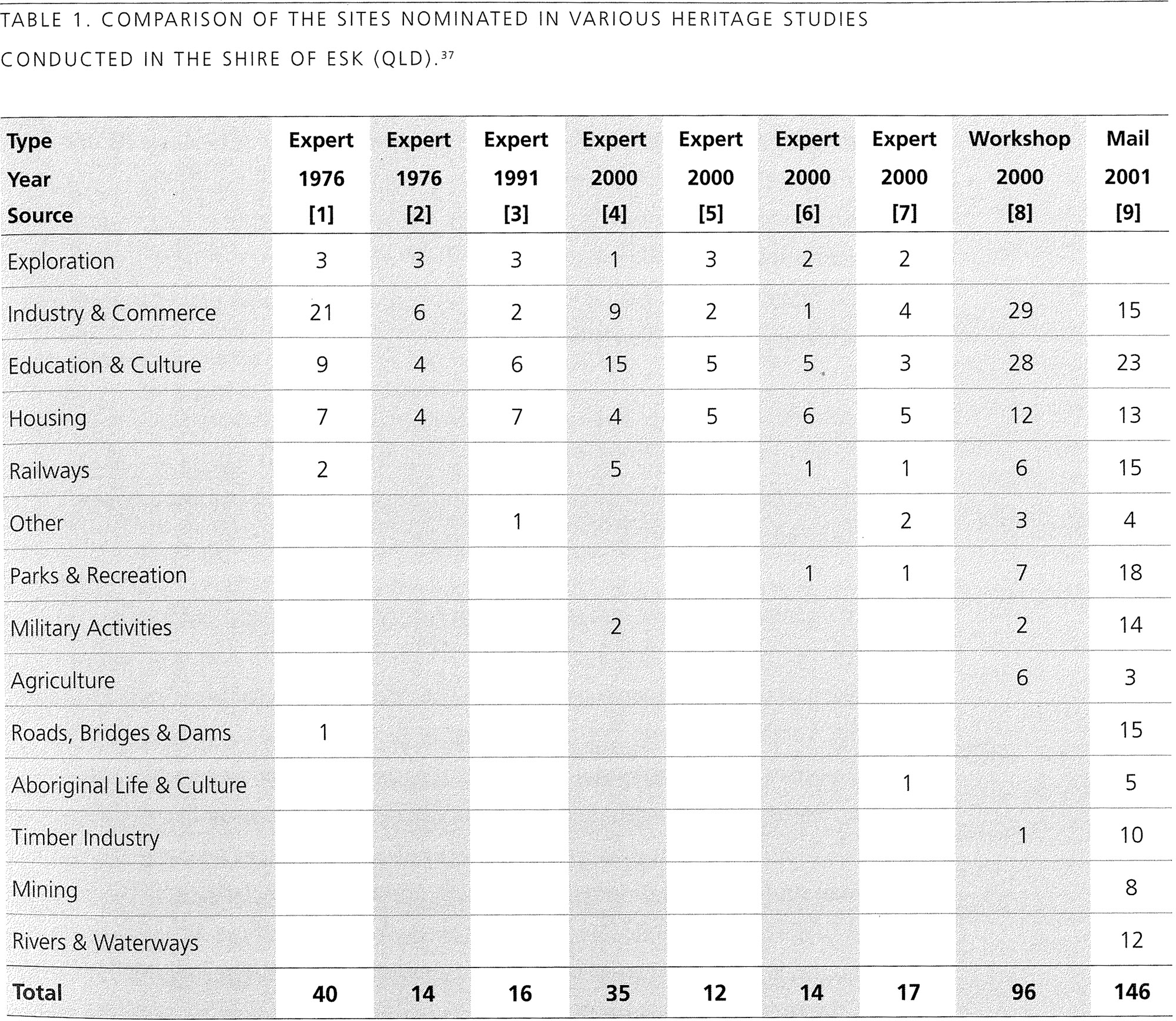

The dichotomy between natural and cultural heritage that is so deeply ingrained in the institutional structures and staff of many non-Indigenous conservation agencies has little meaning to the general public when asked to nominate places of heritage value. Indeed, the most frequently mentioned places in open-ended anonymous community surveys were natural heritage items to which the community has a social attachment.(36) The key problem is to sort out whether these are true heritage places with cultural and social values attributed to them or whether these are places with a high community amenity value. In 2000, Peter Savage conducted a heritage assessment in the Shire of Esk southwest of Brisbane, and compared the results of previous expert-driven as well as community workshop-based heritage studies with those from open-ended anonymous questionnaires.(Table 1) Both the range of site types and the overall number of sites proposed is much greater.

To recapitulate, the survey method provides a more accurate reflection of a community's heritage as it also captures members of the silent majority, who for various reasons would not attend workshops or public meetings about heritage, but who, too, are taxpayers and who have a stake in a local government heritage management strategy.

Also in 2000, English Heritage carried out a quantitative survey of over 1,600 adults to assess their understanding of heritage and followed up with a qualitative study of 3 focus groups.(38) The study found that the general public was cognizant of historic homes and palaces, but that understanding of the other aspects of heritage was limited. Moreover, British citizens of non-British ethnicity showed a much greater interest in other forms of heritage. When prompted, most respondents had a very personal concept of heritage, which also translated to different priorities for preservation funding. The wider community also demonstrated the underlying importance of heritage values and the meaning of places, as well as the relevance of these places to stimulate their own emotional well-being.

Such surveys provide a much greater selection of sites that are significant to the community, which allows for more holistic decisions. As part of social science research, they can also give us a good understanding of a community as a whole and its priorities.

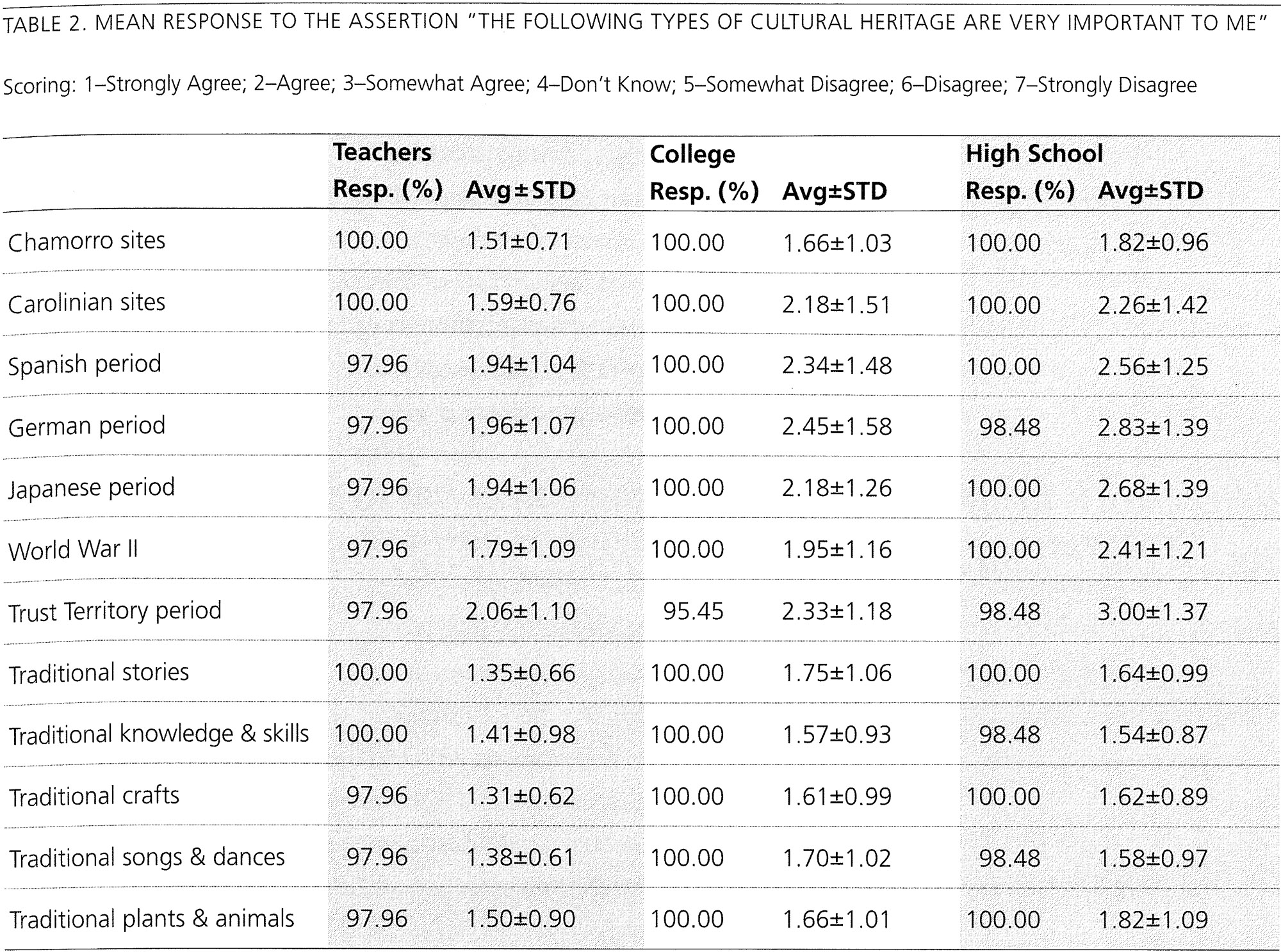

An example of priorities can be drawn from a study carried out in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands in 2001. Using a 7-point Likert scale, respondents drawn from the education sector were asked to rate their reaction to a number of assertions regarding classes of heritage.(39) The responses show that heritage places of all periods as well as non-tangible expressions of heritage, such as traditional knowledge and skills, were important or very important to the respondents.(Table 2) The comparatively small standard deviations (1 rank or less) show a relative uniformity of opinions on the matter. Because this kind of question treats each type of heritage equally, it provides a good overview of the range of attitudes towards heritage in the surveyed community.

|

Table 2. Mean average response to the assertion, "The following types of cultural heritage are very important to me." |

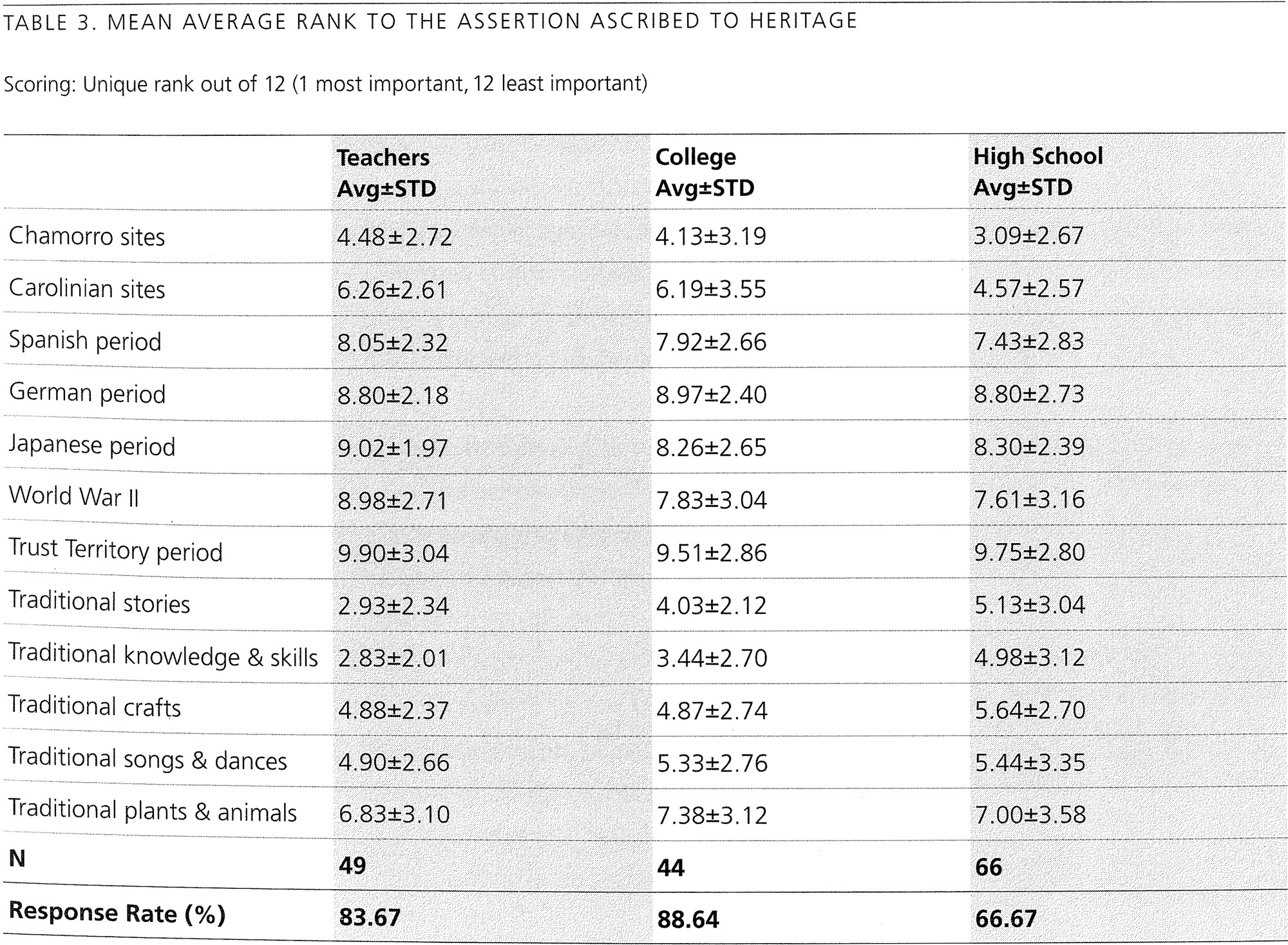

But such surveys can also be extended to gain perceptions of the absolute value of heritage to a community, as well as the relative value of heritage places or classes of heritage places against each other. The value of such information for decision-making in a political climate of restricted funding cannot be overestimated. To ascertain the relative significance of the various phases and aspects of heritage in the Northern Mariana Islands, a second question was posed, which required the respondents to rank their preference from 1 to 12. This question was separated from the previous one by a series of other attitudinal questions.(Table 3)

|

Table 3. Mean average rank to the assertion ascribed to heritage. |

As expected, this arrangement forced a substantial separation of opinion. It elicited the information that traditional stories, knowledge, and skills were far more important elements of cultural heritage than archeological sites of the Indigenous Chamorro culture. And these sites, in turn, were far more important than traditional crafts and dances. Colonial heritage sites of the Spanish, German, Japanese, and World War II periods all ranked very low. Yet, it tends to be these sites that see most of the management investment.(40) The study was repeated in 2004 with an increased sample population, but the results are still to be analyzed. Repeating such studies at regular intervals will permit an assessment of shifts in opinion over time.

While heritage surveys give detailed insights into the perception of heritage among the wider community, and while such surveys can provide information on the relative significance of classes of heritage sites, they ostensibly provide us with only a snapshot of the status quo. Yet, at the same time, by targeting emerging population members, such as college and high school students, we can gauge their awareness and can, within reason, predict any value shifts likely to happen in the immediate future.

If heritage is to have a future, its management has to be sustainable, both economically and socially. Moreover, socially sustainable interest in heritage will ensure that adequate funding is allocated by the government. Thus, it is incumbent on heritage managers to work towards creating favorable conditions for heritage to flourish in the future.(41)

Public Education and the Next Generation

The obvious target is the next generation of citizens. Cultural heritage must have a firm place in school curriculum and in curriculum development.(42) There are a growing number of examples in the United States where historic preservation and archeology are being introduced in classroom settings. But is that enough?

There is also a good deal of public education taking place, ranging from the annual Historic Preservation Month to site specific campaigns. Looking at this activity from the outside, it is about celebrating selective elements of the past. What relevance does such a heritage place have to disadvantaged recent immigrants? To families with meager resources?

Historic preservation must be actively and holistically promoted to the general public. Consider for a moment that heritage places are deemed significant based on the values that the community projects onto them. Consider further that historic preservation as an activity is only important as long as the community values it. Finally, take into account that the values are mutable qualities that will change over time. It follows that the heritage community needs to influence and foster those values that are supportive of heritage protection, those values that currently give significance to the properties that, after due consideration, are deemed worth maintaining and conserving. In essence, the heritage community needs to engage in a process that perpetuates these values.

While there is a great deal of historic preservation advocacy, we need to develop a medium- and long-term historic preservation strategy at the national, state, and local levels that promotes heritage and historic preservation in a fashion that is community-owned and sustainable. Such a strategy has to be founded on an in-depth understanding and appreciation of the heritage values held by the community, as well as an understanding of the attitudes towards heritage encouraged by planners and social service personnel. Ideally, such studies are carried out first at the local level, creating a patchwork quilt of values and attitudes. Commonalities can be extracted to the state and ultimately to the national level.

The benefits of embarking on such a process are twofold. First, we are gaining an insight into the nature of values the community—and that includes the silent majority—holds with respect to its heritage and historic preservation. Second, simply by embarking on this process and engaging the whole community, we demonstrate to the community that their views are widely sought and recognized as important to the heritage profession. If that effort is followed up by concerted action, both in the heritage planning and protection area, but also in the heritage publicity and education area, then our past will not only have a future, but we can also shape that future.

About the Author

Dirk H.R. Spennemann is an associate professor of Cultural Heritage Management at Charles Sturt University in Albury, Australia. He may be reached at dspennemann@csu.edu.au.

Notes

1. This essay was adapted from a keynote address delivered at the international luncheon at the California Historic Preservation Conference, Riverside, CA, May 13, 2005.

2. William J. Murtagh, Keeping Time: The History and Theory of Preservation in America (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, 1997); M. Pearson and S. Sullivan, Looking After Heritage Places (Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press, 1995).

3. I. McBryde, Who Owns the Past: Papers from the Annual Symposium of the Australian Academy of the Humanities (Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press, 1985).

4. See David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

5. J.E. Tunbridge and G.J. Ashworth, Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict (Chichester, England: John Wiley, 1996) and Rosemary Hollow and Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "Managing Sites of Human Atrocity," CRM Magazine 24 no. 8 (2001): 35-36.

6. M.E. Weaver, Conserving Buildings: Guide to Techniques and Materials, rev. ed. (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, 1997); also Murtagh, Keeping Time; Pearson and Sullivan, Looking After Heritage Places.

7. D.D. Rypkema, The Economics of Historic Preservation: A Community Leader's Guide (Washington, DC: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1994).

8. Weaver, Conserving Buildings; also Murtagh, Keeping Time.

9. David W. Look and Dirk H.R. Spennemann, eds., Conservation Management of Historic Metal in Tropical Environments, Background Note No. 11 (1994).

10. M. Lockwood and Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "Value Conflicts Between National and Cultural Heritage Conservation—Australian Experience and the Contribution of Economics," in Heritage Economics: Challenges for Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Development in the 21st Century (Canberra, Australia: Australian Heritage Commission, 2001).

11. Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "Your solution, their problem. Their solution, your problem: The Gordian Knot of Cultural Heritage Planning and Management at the Local Government Level," paper read at the Planning Institute of Australia Conference 2004: Planning on the Edge (Hobart, February 2004).

12. A. Bickford, "The patina of nostalgia," Australian Archaeology 13 (1981): 1-7.

13. Australian Heritage Council, "World Heritage—What Does It Mean?" (2004) http://www.deh.gov.au/heritage/worldheritage/about.html, accessed on February 20, 2006.

14. See, for instance, the mission statement of Canadian Heritage: "Towards a more cohesive and creative Canada."

15. German concentration camps are among the more recognizable examples of such places. See Tunbridge and Ashworth, Dissonant Heritage.

16. K. Bhatnagar, "Adaptive Re-use of Historic Properties in India: Aesthetics and Appropriateness," presented at the UNESCO Conference on Adaptive Re-use of Historic Properties in Asia and the Pacific, Penang and Melaka, Malaysia, May 1999; also K. Murali, "Chennai's architectural heritage," Frontline [Dehli] 20 no. 10 (2003).

17. M. Barry, "The Destruction of Bamyan," World Heritage Review 20 no. 1 (2001): 4-13.

18. John Poppeliers, "A New World Order and Historic Preservation," CRM Magazine 17 no. 3 (1994): 3-4.

19. C. Kaiser, "Crimes Against Culture—The Former Yugoslavia," UNESCO Courrier (September 2000).

20. L. Cuba and D.L. Hummon, "A Place to Call Home: Identification With Dwelling, Community and Region," The Sociological Quarterly 34 no. 1 (1993): 111-131; J. Dixon, "Displacing Place-Identity: A Discursive Approach to Locating Self and Other," British Journal of Social Psychology 39 (2000): 27-44; M.T. Fullilove, "Psychiatric Implications of Displacement: Contribution from the Psychology of Place," American Journal of Psychiatry 153 no. 12 (1996): 1516-1533; M.C. Hidalgo and B. Hernandez, "Place Attachment: Conceptual and Empirical Questions," Journal of Environmental Psychology 21 no. 3 (2001): 273-281; L.C. Manzo, "Beyond House and Haven: Toward a Revisioning of Emotional Relationships With Places," Journal of Environmental Psychology 23 (2003): 47-61.

21. D. Chapman, Natural Hazards, 2nd ed. (Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press, 1999).

22. Historic Preservation Division and Georgia Department of Natural Resources, After the Flood: Rebuilding Communities Through Historic Preservation (Atlanta: Historic Preservation Division, Georgia Department of Natural Resources 1997).

23. K. Graham and Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "The Importance of Heritage Preservation in Natural Disaster Situations," International Journal of Risk Assessment and Management (forthcoming).

24. Spennemann, "Your solution, their problem."

25. Murtagh, Keeping Time; G. Davison, "A Brief History of the Australian Heritage Movement," in A Heritage Handbook, ed. G. Davidson and C. McConville (Sydney, Australia: Allen and Unwin, 1991); L. Smith, "Significance Concepts in Australian Management Archaeology," in Issues in Management Archaeology, ed. L. Smith and A. Clarke (Brisbane, Australia: University of Queensland, 1996).

26. S. Canning and Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "Contested Space: Social Value and the Assessment of Cultural Significance in New South Wales, Australia," in Heritage Landscapes: Understanding Place and Communities: Proceedings of the Lismore Conference, ed. M.M. Cotter, W.E. Boyd, and J.E. Gardiner (Lismore New South Wales, Australia: Southern Cross University Press, 2001): 457-468.

27. See, for instance, LandCare in Australia, http://www.landcareonline.com/, accessed on February 20, 2006.

28. Spennemann, "Your solution, their problem."

29. C. Pocock, "Identifying Social Values in Archival Sources: Change, Continuity and Invention in Tourist Experiences of the Great Barrier Reef," in The Changing Coast, eds. Veloso Gomes, Taveira Pinto, and Luciana das Neves (Porto, Portugal: Eurocoast/EUCC, 2002): 281-290; also Spennemann, "Your solution, their problem."

30. New South Wales Heritage Office, Community-based Heritage Studies (Sydney, Australia: New South Wales Heritage Office, 2001).

31. Spennemann, "Your solution, their problem." An example are historical societies that are usually included as key stakeholders in any heritage identification process, yet considering both the age structure and ethnicity of most historical societies, they are not representative of the population.

32. Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "Multicultural Resources Management—A Pacific Perspective," Historic Preservation Forum 7 no. 1 (1993): 20-26.

33. Spennemann, "Your solution, their problem," for case examples from Albury, New South Wales.

34. K. Harris, "The Identification and Comparison of Non-market Values: A Case Study of Culcairn Shire (NSW)" (BAppSci (Hons) thesis, Charles Sturt University, 1995); Dirk H.R. Spennemann and K. Harris, "Cultural Heritage of Culcairn Shire: Some Considerations for Strategic Planning," Johnstone Centre of Parks, Recreation and Heritage Report 71 (Albury, New South Wales, Australia: Charles Sturt University, 1996); Dirk H.R. Spennemann, M. Lockwood, and K. Harris, "The Eye of the Professional vs. Opinion of the Community," CRM Magazine 24 no. 2 (2001): 16-18.

35. Peter Savage, "Shared Values, Shared Future: The Role of Heritage Social Values in Developing a Sustainable Heritage Tourism Industry in the Shire of Esk" (MAppSci thesis, Charles Sturt University, 2001).

36. Ibid. See also Harris, "The Identification and Comparison of Non-market Values;" Spennemann et. al., "Cultural Heritage of Culcairn Shire."

37. Table data adapted from Savage, 2001.

38. See English Heritage, Attitudes towards the Heritage, research study (2000).

39. Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "Teacher and Student Perceptions of the Cultural Heritage of the CNMI: An Empirical Snap-shot," The Micronesian Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 2 no. 1-2 (2003): 50-58.

40. Ibid.

41. Ibid.

42. Spennemann and Meyenn, "Melanesian Cultural Heritage Management Identification Study."