Article

Black Soldiers and the CCC at Shiloh National Military Park

by Timothy B. Smith

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp at Shiloh National Military Park in Tennessee looked the same as any other camp of the era. The living quarters were neatly arranged. There were latrines, cooking areas, parking areas for wheeled vehicles, commissary, quartermaster, and medical facilities. The men milled around, going about their business under watchful supervision of the officers. Above it all flew the United States flag. Nothing was out of the ordinary except the men themselves. This camp, situated near Pittsburg Landing on the battlefield of Shiloh, was for African American veterans.(1)

The year was 1934, and the Federal Government had just sent more than 400 black World War I veterans to Shiloh to work in two CCC camps.(2) Over the course of eight years, the men improved the park and aided in the battlefield restoration that the park founders had so dearly desired. These black veterans who had risked their lives for their country in the Great War now worked to preserve a battlefield of an earlier generation.

Shiloh had special meaning for these men: The Civil War battlefield played a major role in the Union's eventual victory over the Confederacy. Sadly, even as they restored one of the very spots where their freedom had been partially won, they faced Jim Crow segregation and other forms of racism.(3) Their story is one of many such paradoxes, of honorable work that benefited the nation, and of prejudicial treatment in the national parks. It offers valuable insight into the nature of race relations, government New Deal work, and the management of cultural resources in the United States during the Great Depression.

Shiloh and the Civilian Conservation Corps

Among the chief beneficiaries of the New Deal's job creation programs were Shiloh and other national parks, to which thousands of laborers were sent to construct, rehabilitate, and restore. In the case of Shiloh, the Civil Works Administration (CWA) employed several hundred local men from Hardin and McNairy counties on erosion control projects, road maintenance, and excavations at Shiloh's Indian mounds. The Public Works Administration (PWA) also provided money for new visitor, employee, and administrative facilities and funded several writers who studied and wrote about Shiloh's history. The Bureau of Public Roads surveyed the park and funded road modernization projects. By far, however, the CCC was the dominant New Deal program at Shiloh.(4)

Normally, the CCC employed young men between the ages of 18 and 25.(5) Although World War I veterans were much older, they were allowed to work in the CCC because of the efforts of the "Bonus Army." Wanting to cash in their congressionally appropriated service bonuses, the unemployed veterans marched on Washington, DC, in the summer of 1932 to demand their money. What they received instead was a rough handling by Douglas McArthur and the army, along with an offer to join the CCC. Some 200,000 World War I veterans ultimately joined the CCC, 30,000 of them black veterans.(6)

Daily Life at the Shiloh Camps

The first of the two black CCC camps at Shiloh, Tennessee Camp MP-3 (Camp Young), was established on July 15, 1933.(7)(Figure 1) Made up of men from Company No. 2425, Camp Young was situated at the southwestern corner of the park. The earliest enrollees lived in tents "deep in the shade of the large white oaks," as one eyewitness described it, while they built permanent quarters on the other side of Shiloh Branch.(8) Ultimately, the camp boasted 18 buildings, with the 4 barracks aligned in 2 rows with a "beautiful green carpet of grass" in between, a mess hall and recreation hall on opposite ends of the green, large oaks, and numerous flowerbeds. The camp had an initial enrollment of approximately 200 men from across the South.(9)

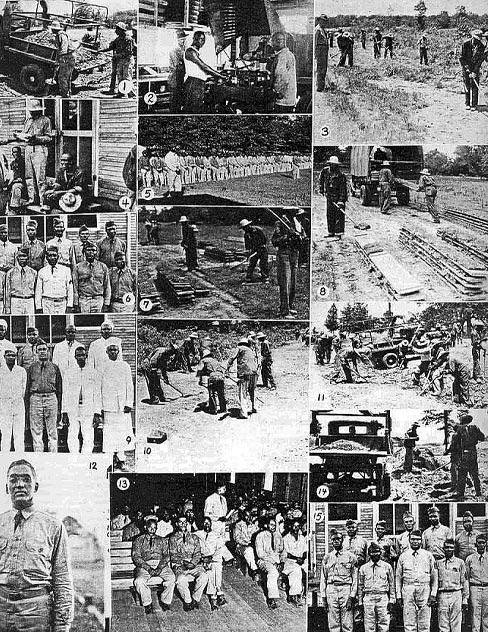

The second camp, Tennessee Camp MP-7 (Camp Corinth), was established nearly a year later on June 14, 1934, approximately 22 miles southwest of the park.(10)(Figure 2) Enrollment at Camp Corinth fluctuated more than at Shiloh, with numbers ranging between 150 and 200 enrollees, most coming from the South also.(11)

|

Figure 2. This 1937 photo collage of Camp Corinth enrollees offers insight into different aspects of camp life and work life. (Courtesy of Middle Tennessee State University.) |

The two camps had similar organizational structures. White military officers on detail oversaw the camps: An army captain or navy lieutenant normally served as camp commander, and a junior officer served as second in command. A camp surgeon was similarly detailed from the military. Each camp also had a corps of white technical officers who led the work groups and advised on engineering, forestry, and other technical matters. Camp foremen who served as clerks, mechanics, historical assistants, and landscape personnel came and went. Enrollees with specialized skills were detailed as foremen, drivers, clerks, storekeepers, or cooks and were given supervisory responsibilities over other enrollees. All worked closely with the Shiloh National Military Park superintendent, who developed the work programs.(12)

The camps also resembled each other in their physical arrangement. Originally, Camp Young consisted of two office buildings (one with an engineer's room), several tool storage areas, a mess hall, and a recreation center. Four large bunkhouses eventually replaced the original tents. By 1941, the camp had 18 permanent and 6 portable buildings heated by coal stoves and a modern, enclosed latrine and septic system. The enrollees burned their refuse daily, hauled away other garbage, and initially drew water from a nearby spring on Shiloh Branch. Like Camp Young, Camp Corinth had an ample latrine and septic system. The camp drew water from a 134-foot deep well that furnished "ample water which is potable without chlorination."(13)

Upon entering service at the Shiloh camps, the enrollees were given a medical examination and inoculations and were issued uniforms. Most brought personal items from home: a nice suit for going to town, a musical instrument. An "Oath of Enrollment" was also required, with the men promising to remain in the camp for at least six months and obey the orders of their superiors. Some enrollees were sent to conditioning camps to develop the health and fitness required to perform the work. The men were paid $30 a month, $25 of which was sent home to their families. Enrollees who moved up in the ranks over time received higher wages. This introduction to the CCC was similar to the experience of thousands of other whites and blacks in camps across the nation.(14)

To make sure the enrollees at the Shiloh camps remained in good physical health, the camp surgeon visited them daily and examined the men for venereal diseases once a month (kitchen personnel were examined more frequently). The buildings were also inspected monthly, and a camp safety program required weekly meetings, safety posters, fire drills, and proper work safety precautions. The state board of health approved all of the health measures.(15) Laundry was thoroughly checked for "bed bugs or other vermin" and sent to the cleaners weekly.(16)

The daily routine in the two CCC camps resembled those at other camps, white or black. Reveille sounded at 6:00 a.m., followed by calisthenics and breakfast at 6:45 a.m. The men worked from 8:00 a.m. until noon. After lunch, they returned to their job sites and worked until 4:00 p.m. They had an hour to themselves before reporting in dress uniform for supper at 5:30 p.m. Lights went out at 10:00 p.m., with taps played 15 minutes later. Saturdays were a time of leisure or field trips, unless work had been missed during the week due to bad weather. Sundays and holidays were days of rest and, if the men so chose, worship.(17)

The Camp Corinth enrollees worked on the 17 miles of the Shiloh-Corinth Highway connected to the park. Their two major duties were road improvement and telephone line construction. They maintained the highway and the rights-of-way and adjoining areas, graded the sides of the road, planted grass and laid sod, planted trees and shrubs, and collaborated on transplanting projects. Where drainage and erosion were problems because of years of excess pasturing and over-cultivation, they built check dams and riprap or improved or sloped banks. By example, they encouraged the local farmers to adopt similar conservation measures on their farms, which resulted in terracing and better methods of farming. The enrollees also placed pipelines and conduits along the road and removed tree stumps, the ultimate goal being the "general beautification of [the] highway."(18)

Camp Young enrollees performed a variety of jobs in the park, including roadwork, erosion control, landscaping, forestry management, and fire prevention. The workers streamlined drainage in the park and the national cemetery, building small dams at strategic locations to prevent erosion. At the Confederate general Albert Sidney Johnston death site, they built 96 dams. They also filled in and beautified an eroded area called "Dead Man's Gravel Pit," which was so named because of a rockslide that had killed three workers in 1899. They created a test area in Rea Field on Shiloh Branch for experimenting with new methods of erosion control and new types of wood and stone dams.(19)

Most of the Camp Young enrollees worked on road cleanup and the general beautification of the park, and several features they built still exist, including the guardrails along the tour route, a bridge near the mouth of Dill Branch, and seven parking areas within the park. They also built foot trails, leaf pits, a fire tower, a brick restroom at the headquarters area, picnic areas, and a 50-foot protection wall to keep a road from being undercut. At the campsites, they built several buildings, razed others, installed a camp phone system, laid approximately 450 feet of water pipe, and removed several non-historic roads. They also gathered firewood and performed other odd jobs.(20)

When not working, camp life revolved around recreation opportunities and education programs for which the CCC was well known. At Corinth, the camp had the benefit of "ample class-rooms, libraries, black-boards and textbooks, and especially a sympathetic co-operation of the Commanding Officer." Yet in 1935, only about 30 percent of the enrollees took advantage of the classes. One inspector noted "it has not been an easy matter to get any major percentage of their number interested in any form of education training." The average educational level of the men was 4th grade, and 24 men had no schooling at all.(21)

The apathy changed when African American military officer and former coordinator of Tuskegee Institute, Captain Toliver T. Thompson, became both camps' educational director. It was said he "injected a new spirit into the educational and recreational work here." Thompson implemented many new programs, as well as scientific films and lectures on topics such as the battle at Shiloh, tree pruning, and explosives. The educational staff kept the training at an elementary level, teaching evening courses in arithmetic, reading, spelling, history, writing, English, and citizenship. These educational activities were important to a generation of Americans who did not have much formal education, and especially to the black enrollees who had even less because of segregation.(22)

The vast majority of enrollees were interested in vocational training, and the corps shifted its focus accordingly. The men were taught woodworking, blacksmithing, carpentry, auto repair, and other trades, including "rabbit production." Some of their efforts resulted in a profit, which the company commander placed in a bank account at the Farmers and Merchants Bank in Corinth.(23)

The camps did well in monthly and annual inspections. Camp numbers fluctuated depending on discharges, new recruits, sickness, and an occasional absence without leave. Camp Young won the title of best in its district for 1935, earning a tremendous compliment from the Army inspector: "It is with great pleasure that I select Co. 2425, MP-3, as the outstanding company in my entire district. The appearance of the camp is excellent. The morale is high, and the conduct of the members is highly commendable. I do not believe that I have seen a better camp in my two years of contact with the CCC." The Corinth camp won the award for 1936.(24)

Segregated Camps at Shiloh

The major differences between white and black camps in the CCC were the segregation and other forms of racism that pervaded camp life and the local opposition that the black camps encountered. It appears that, at first, Tennessee state officials were uncertain how even to manage the public reaction to such camps. The State Commissioner of Agriculture, O.E. Van Cleve, mentioned to Tennessee Governor Hill McAlister that "should you be called upon to designate a particular project for colored camps you might suggest the National Parks." Federal officials agreed, directing "complete segregation of white and colored enrollees" and establishing the black camps at Shiloh and other "military reservations."(25)

Despite the precautions, area residents complained about having black camps nearby. United States Senator Kenneth McKellar of Tennessee told Governor McAlister, who had chosen the camp locations, that the "colored camps are problems, and the only way they can be managed is to take them up with the local authorities before making a recommendation." Likewise, the governor felt that "it [is] far better for the colored race not to have these camps in our State if they must be established where race hostility will immediately develop." McNairy county was particularly vocal in its objection to black camps, with citizens issuing a statement in the McNairy County Appeal that "[voiced] the sentiment of our entire population." "We do not want them here," the statement read, "as ours is not a negro community, and we do not know how to handle them." The locals raised such a furor that the projected camp at nearby Adamsville was changed from a black to a white camp.(26)

In 1937, a resident of Corinth wrote to President Roosevelt himself:

The Negro CCC camp is near here and the houses are rented to these Negros [sic] and family while the land is rented to the Government. A poor farmer is unable to pay big rent for a house and has to have land to work so they are left out here. While the Negros [sic] feed families and relatives from the camp. Aren't these barracks built for them. Please look into this.(27) |

The men themselves seemed to be highly motivated and satisfied, although some complained about unfair treatment. At Camp Young, the enrollees and their foremen were separated from the white officers in the mess halls and served food of lesser quality. "The Army officers have steaks, salads, desserts and all this was and is paraded before our eyes," one man reported, and he also complained that they were forced to use a bathhouse located several hundred feet away from their quarters because the one in their quarters was reserved for the army officers. "What is good enough for one is good enough for the others," wrote one of the foremen.(28) An enrollee at Camp Corinth, writing under a pseudonym, complained to the Veterans Administration about "this commander that won't proper feed us," and accused the camp commander of diverting money allotted for food to buy paint for his own quarters. "We feel we should have a fair deal such as is due," he protested, "Please let someone come."(29)

In response, the Veterans Administration sent a special investigator who, upon discovering that the signature (I.E. Smart) was fictitious, concluded that the letter was written in reaction to the camp's strict discipline. The investigator told the enrollees that "they should be appreciative of what the Government is doing for them." Although the men said they were well fed, they expressed their desire for simpler food such as cornbread and buttermilk—something more akin to what they were used to at home. The investigator explained that they needed certain calorie levels so they could perform their work but recommended that the camp commander look into broadening the menu.(30)

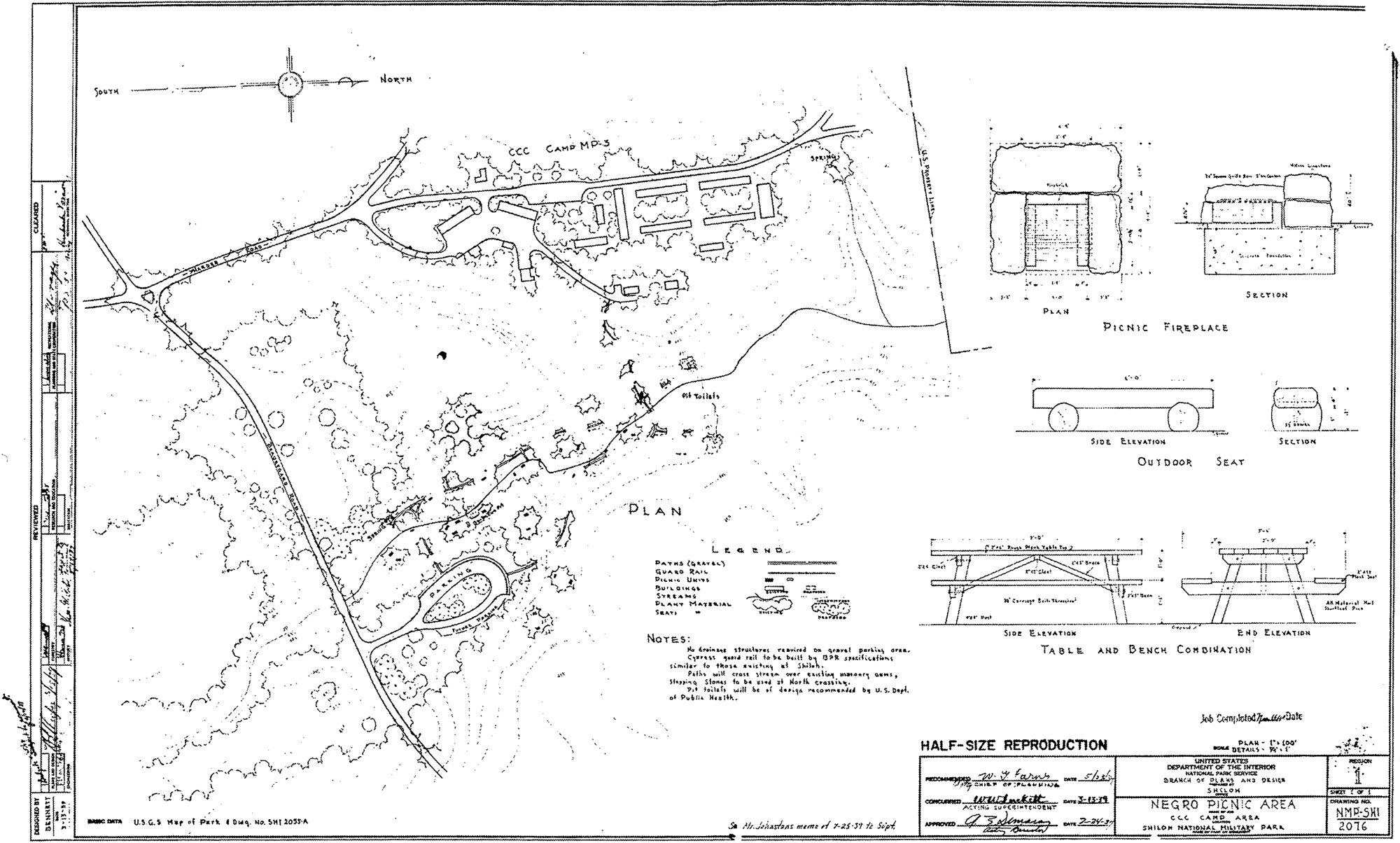

Segregation was the norm. Although the enrollees had built picnic areas at the Indian mounds and Rea Springs, they were not allowed to use them because the areas were reserved for whites only (they had to build their own picnic area adjacent to their camp on Shiloh Branch).(Figure 3) When family and friends visited, the enrollees had to remain in designated areas. Such face-to-face encounters with segregation and other forms of racism at Shiloh remained in the minds of the black veterans who had served their country twice on battlefields: first in combat and later in conservation.(31)

|

Figure 3. This 1939 site plan of a picnic area for black CCC enrollees and their guests at Shiloh National Military Park is a reminder of the segregation and other forms of racism that pervaded camp life. (Courtesy of the National Park Service.) |

Conditions were such that some of the enrollees complained to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the fall of 1937 about the treatment of blacks at Shiloh. "We are advised," the NAACP leadership informed the CCC, "that a gang of outsiders working around the camp steal the clothing and shoes of the enrollees for which the enrollees have to pay; that no serious effort is made by the officers to patrol the camp so that the property of the enrollees can be protected; that there is a further complaint about food." The letter prompted another investigation by CCC leaders.(32)

The forms of racism practiced or tolerated at Shiloh were nothing out of the ordinary for the time. Rather, they were indicative of the racism that existed in the CCC and many other New Deal agencies. Housing segregation in the Tennessee Valley Authority and Federal Housing Authority occurred frequently. Blacks were often paid less than whites in many New Deal programs. Racial discrimination and segregation ran rampant particularly in the South, where Federal Government officials deferred to local laws and practices.(33)

Long-term Impact of the Shiloh CCC Camps

Camps Young and Corinth continued to function independently until October 31, 1941, when the two were joined into NP-9, and enrollees worked on both the park and the roadway. Some of the men were assigned to a short-term "side camp" at Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga, Tennessee; others worked at nearby Pickwick Dam. The outbreak of World War II marked the beginning of the end for the CCC camps, with the extra manpower and labor redirected towards the war effort. Shiloh's combined CCC camp, reduced in status to a side camp, was disbanded on April 15, 1942.(34)

The contributions of the CCC and other New Deal programs to the development and management of the national parks are comparable to those of the National Park Service's Mission 66 program.(35) The long list of projects at Shiloh alone illustrates the enormity of that legacy and the importance of understanding the diversity of the CCC experience in evaluating the resources where CCC activities took place.(36) More difficult to quantify but of tremendous significance was the impact that the CCC camps had on their enrollees. The 30,000 black World War I veterans were a small but important part of the New Deal effort. In many national and state parks, they performed good, solid work and made substantive and lasting contributions to the nation.

However, their CCC experience was a double-edged sword: The vocational, financial, and educational opportunities the CCC provided lay under the mantle of segregation and other forms of racism that affected African Americans nationwide. While work and camp life were supposed to be regulated uniformly across all camps, black enrollees had to endure prejudicial treatment that white enrollees never faced, much of it codified by the Federal Government. Sadly, African American veterans were denied full equality in the CCC camps, even on a hallowed battlefield where their very freedom and citizenship had been partially gained.

At the same time, the New Deal's relief and recovery programs also helped African Americans on a fundamental level by providing work, food, housing, and educational opportunities to those in need of assistance. Although segregation had permeated New Deal programs, the New Deal marked an important point in the steady march towards equality for African Americans that led to the desegregation of the United States military in 1947 and the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.(37)

Of all the benefits accrued from the New Deal, perhaps the most profound was the renewed sense of purpose the CCC experience instilled in the enrollees and, in the case of the Shiloh camps specifically, in the middle-aged men whose service in World War I had been too quickly forgotten. They became actively engaged in the important work of improving a national park for the benefit of present and future generations. One camp inspector said it best when summing up the results of the educational and work programs in 1939: "Results as yet Intangible Mentally and Spiritually as affecting rehabilitation of vets, but indicated from present participation percentage of 98.96."(38)

About the Author

Timothy B. Smith is a park ranger at Shiloh National Military Park. He is author of This Great Battlefield of Shiloh: History, Memory, and the Establishment of a Civil War National Military Park, Champion Hill: Decisive Battle for Vicksburg, and most recently The Untold Story of Shiloh: The Battle and the Battlefield.

Notes

1. The treatment of black soldiers in Civil War history is much debated. Most of the attention focuses on northern recruitment of black regiments and their wartime service. More recent research examines the possibility of black soldiers in the Confederate Army. Yet, the story of Shiloh does not usually include African American soldiers on either side. Coming early in the Civil War before the Lincoln Administration had made any decisions about the fate of former slaves, Shiloh had no United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiments and few individual black men among the masses of soldiers that fought on April 6-7, 1862. Even so, the history of Shiloh does have hundreds of black soldiers in it. For African American soldiers in the Union Army see Dudley Taylor Cornish, The Sable Arm: Black Troops in the Union Army, 1861-1865 (New York, NY: Longmans, Green and Company, 1956) and Joseph T. Glatthaar, Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers (New York, NY: The Free Press, 1990). For African Americans in the Confederate Army, see Richard Rollins, ed., Black Southerners in Gray: Essays on Afro-Americans in Confederate Armies (Murfreesboro, TN: Southern Heritage Press, 1994).

2. Established in 1894 under the War Department, Shiloh National Military Park entered the National Park System in August 1933, when it and other military parks and national cemeteries were transferred to the National Park Service. The preservation of Civil War battlefields as national parks was (and still is) widely considered to be an appropriate way of commemorating the men whose bravery and sacrifice during the Civil War changed the course of American history. For Shiloh, see Timothy B. Smith, This Great Battlefield of Shiloh: History, Memory, and the Establishment of a Civil War National Military Park (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2004).

3. Jim Crow segregation grew out of the sectional reconciliation that had begun in the 1870s but had deteriorated by the 1890s, allowing segregation to dominate race relations. Segregation received official sanction in the 1892 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision, and it was the norm in the 1930s when the Federal Government created the CCC. See James M. McPherson, Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction (New York, NY: Knopf, 1982); Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (New York, NY: Harper Collins, 1989); for race and segregation, see David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in Memory and Reunion (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001) and C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, 3rd ed. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1989).

4. Charles E. Shedd, A History of Shiloh National Military Park, Tennessee (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1954), 45-46; "Research Studies Made During the CWA Period, Shiloh National Military Park," in Historical Reports: Research Reports on Army Units in the Army of Tennessee, Vertical File, Shiloh National Military Park.

5. Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed the idea of a civilian conservation corps during his 1932 presidential campaign. He signed the CCC into law in March 1933—not long after his presidential win.

6. "Dedication of THC Marker for CCC Co. 2425, MP-3, Shiloh National Military Park, July 14, 1990," in Dedication Remarks for Placement of CCC Marker, July 14, 1990, Vertical File, Shiloh National Military Park; John C. Paige, The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1985), 97. For African Americans in the CCC, see Olen Cole, The African-American Experience in the Civilian Conservation Corps (Tallahassee: University Press of Florida, 1999).

7. The camp was originally organized in June at Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia.

8. The permanent quarters were completed in November 1933.

9. "ECW Monthly Progress and Cost Report," February 1937, RG 79, E75, Box 7, National Archives and Records Administration, hereafter cited as NARA; "Dedication of THC Marker for CCC Co. 2425, MP-3, Shiloh National Military Park, July 14, 1990," in Dedication Remarks for Placement of CCC Marker, July 14, 1990, Vertical File, Shiloh National Military Park; "Camp Inspection Report," October 3, 1938, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; "2425th Company, MP-3, Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee," Official Annual Civilian Conservation Corps "C" District, Fourth Corps Area – 1937, Patsy Weiler Collection, Albert Gore Research Center, Middle Tennessee State University, hereafter cited as MTSU. The Official Annual is also in the CCC in Tennessee Collection, Tennessee State Library and Archives, hereafter cited as TSLA. See also Civilian Conservation Corps, RG 93, TSLA, for Tennessee camps. The enrollees came from Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Louisiana, Tennessee, and South Carolina.

10. Like MP-3, MP-7 had begun operation elsewhere, at Fort McPherson, Alabama, in July 1933, and then moved to Glencoe, Alabama, near Gadsden. Camp MP-7 was called Corinth because of its proximity to the Mississippi border town bearing that name.

11. Smith, This Great Battlefield of Shiloh, 123; "2423rd Company, MP-7, Corinth, Mississippi," Official Annual Civilian Conservation Corps "C" District, Fourth Corps Area – 1937, Patsy Weiler Collection, Albert Gore Research Center, MTSU; "Tennessee Camp MP-7," May 25, 1937; "Emergency Conservation Work Camp Report," November 29, 1935, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; "Camp Report," July 8, 1934; "Camp Report," May 25, 1937; Toliver T. Thompson to J.S. Billups, November 29, 1935, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; Jean Hager Memo, May 25, 1937, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; Shedd, A History of Shiloh, 46. Enrollees came from Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, Tennessee, and Florida. Later, men from New York, New Jersey, and West Virginia also joined the camp.

12. "Rated Members," November 27, 1936, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; "Camp Report," July 8, 1936, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; "Forestry Personnel," November 27, 1936, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; "Army Personnel," November 27, 1936, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; "Camp Report," November 29, 1935, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; "Fourth Enrollment Period Report, Tennessee Camp MP-3," March 31, 1935, Shiloh National Military Park Archives, hereafter cited as SNMP; Paige, An Administrative History, 66. For more information on District C, Fourth Corps Area, see the CCC in Tennessee Collection, TSLA.

13. Later, a pump house was built, with iron piping to all the buildings.

14. Paige, An Administrative History, 74-76.

15. T.J. McVey Report, June 18, 1934, and "Camp Report," November 6, 1937, both in RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; "Camp Inspection Report," October 3, 1938, May 15, 1940, and May 1, 1941, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA.

16. "Camp Report," November 29, 1935, November 27, 1936, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; T.J. McVey Supplementary Report, November 27, 1936, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA.

17. Paige, An Administrative History, 79-82.

18. Camp Report, July 8, 1936, November 27, 1936, May 25, 1937, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; T.J. McVey Construction Report, November 27, 1936; RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; Narrative Report of Tennessee Camp MP-7, March 31, 1935, RG 79, E 42, Box 28, NARA.

19. Erosion Control Memo, March 11, 1935, Series 2, Box 9, Folder 168, SNMP; Alex Bradford to R.A. Livingston, March 31, 1935; RG 79, E 42, Box 27, NARA; Smith, This Great Battlefield of Shiloh, 99. For a detailed look at a particular project, see "Final Construction Report, Shiloh National Military Park, Eastern Corinth, Hamburg-Crump, and Peabody Monuments Roads, project 4A1," Series 1, Box 76, Folder 1126, SNMP. Included are maps, paperwork, and bids for the project.

20. The company also responded to a major flood on the Tennessee River, for which it received letters of commendation from the corps area commander and the Red Cross. See T.J. McVey Report, June 18, 1934; "Camp Inspection Report," May 31, 1939, "Work Project Report Supplemental to Form 11," April 30, 1941, "ECW Monthly Progress and Cost Report," February 1937, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; Alex Bradford to R.A. Livingston, March 31, 1935; RG 79, E 42, Box 27, NARA; "2425th Company, MP-3, Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee," Official Annual Civilian Conservation Corps "C" District, Fourth Corps Area – 1937, Patsy Weiler Collection, Albert Gore Research Center, MTSU.

21. "Report of Education Program," November 29, 1935, "Monthly Camp Education Report," June 1936, "Camp Educational Program," November 27, 1936, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; Fourth Enrollment Period Report, March 31, 1935, SNMP; "CCC Camp Educational Report," May 31, 1939, RG 35, E 115, NARA; Paige, An Administrative History, 86. Educational classes were standard in the early years of these camps.

22. Ibid.

23. "Report of Education Program," November 29, 1935, "Monthly Camp Education Report," June 1936, "CCC Camp Educational Report, May 31, 1939, "Camp Educational Program," November 27, 1936, "Monthly Camp Educational Report," April 1937, "Supplementary Report," May 31, 1939, "Work Project Report Supplemental to Form 11," April 30, 1941, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; "CCC Camp Educational Report," May 31, 1939, RG 35, E 115, NARA.

24. "Camp Report," November 29, 1935, and undated, both in RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; "2423rd Company, MP-7, Corinth, Mississippi," Official Annual Civilian Conservation Corps "C" District, Fourth Corps Area – 1937, Patsy Weiler Collection, Albert Gore Research Center, MTSU; Fourth Enrollment Period Report, March 31, 1935, SNMP.

25. O.E. Van Cleve to Governor Hill McAlister, July 19, 1935, and Secretary of War to Senator Kenneth McKellar, July 15, 1935, both in Hill McAlister Papers, Box 77, Folder 8, TSLA; John A. Salmond, The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-1942: A New Deal Case Study (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1967). The black CCC companies at Shiloh were but two of the nearly 150 such companies at camps nationwide.

26. Kenneth McKellar to Governor Hill McAlister, August 27, 1935; Governor Hill McAlister to Kenneth McKellar, August 30, 1935; John W. Hamilton to Governor Hill McAlister, August 14, 1935; and Ralph Perry to John W. Hamilton, August 15, 1935, all in Hill McAlister Papers, Box 77, Folder 8, TSLA. Further research may reveal the extent to which public resistance to the presence of black CCC camps pushed the activity of the CCC to national parks.

27. "A Corinth Citizen" to President Roosevelt, June 30, 1937, RG35, E 115, Box 199, NARA.

28. Unknown to James C. Reddoch, January 24, 1936, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA.

29. I.E. Smart to "Officers of the Veterans Administration at Washington DC," April 13, 1936, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA.

30. J.S. Billups to J.J. McEntee, July 13, 1936, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA.

31. Chief National Park System Planning Section to Acting Superintendent, July 27, 1939, Series 2, Box 12, Folders 225, SNMP.

32. Charles H. Taylor to Adjutant General, October 5, 1937, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA. Although the CCC investigated the matter further, its results are not documented.

33. John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans, 3rd Edition (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1969), 534-536; Leslie H. Fishel Jr. and Benjamin Quarles, The Negro American: A Documentary History (1967; Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman and Company, 1976), 448, 455, 463; James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, Hard Road to Freedom: The Story of African America (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001), 265-267; Paige, An Administrative History, 94.

34. "Camp Inspection Report," May 15, 1940, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA; Michael A. Capps, "Shiloh National Military Park: An Administrative History" (Shiloh National Military Park, 1993), 43-45. For more information on the side camp, see Series 2, Box 7, Folders 112-113, SNMP. The side camp workers built the Ochs Museum at Point Park.

35. See Timothy M. Davis, "Mission 66 Initiative," CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship 1 no. 1 (fall 2003): 97-101 for more information on Mission 66.

36. Shiloh was one of many national and state parks that benefited from CCC labor.

37. Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom, 523-525, 534, 538; Paige, An Administrative History, 97.

38. "CCC Camp Educational Report," May 31, 1939, RG 35, E 115, Box 199, NARA.